Andrew Choate Interview

Fax: Please state your qualifications and whereabouts.

Andrew Choate: Highly exacerbatable - to self and others (the whole within/ without transcontinental bypass membrane in full effect.)

Lincoln Heights, Los Angeles.

But if Evan Parker's idea that our "roots are in [our] record players" is accurate - and I think it is -, then surely our location (our 'rootedness' if you will) is dependent less on latitude than on attitude. In which case I can be found most regularly enthused or asstonished, the latter typically brought on by the continual discovery of active deprivations aimed at the objects of the former.

Fax: I've heard your record player is special... anything playing at the moment?

AC: I've got two functioning turntables at the moment. One in the back room/ studio for DJ purposes - a cheap direct drive Numark that has two excellent features: it can play records backwards at the touch of a button and it can play at 78rpm, which will be handy when I get all my granddads 78s. He had a pretty big collection he amassed of 20s, 30s and 40s music. I'm not listening to it at the moment but the LP that's sitting on it from the last time I turned it on is a Lafayette Afro Rock Band number called Malik. It was loaned to me by our man on the seafoam side of things, Randono.

My other record player is the creamier of the two, and is protected by Godfrey, a stuffed manta ray with a penchant for licentiousness. It's a Music Hall mmf 5, belt-driven and with a glass plate for the records to spin on. It costs less than the de rigueur wannabe-DJ Technics 1200 standard no-imagination turntable, and looks and sounds a hell of a lot better. It comes with a pair of white gloves to don when flipping the sides. The Sun City Girls' Kaliflower LP is the platter currently available on that side of the home.

But I'm not listening to either at the moment - I'm going through a bunch of György Szabados' music in order to put me in the mindset to generate some questions for him, since I will be interviewing him in a couple of weeks in Serbia. He's a 70 year old piano player who has been making jazz-inflected improv and large ensemble music for many a good moon. Listening to his 1974 quartet album "The Wedding" right now.

John Randono: Actually, the last thing that I heard on Andrew's record player was his lucky thompson, oscar pettiford album, title of which eludes me (maybe andrew can clarify), followed by a carlo actis dato record entitled oltremare...I was so intoxicated by the meal he served: delicately spiced, pickled chrysalis in honeywine vinegar and an exquisite plate of fried moth wings, cooked with a gentle crispness and served to perfection. I remarked that chrysalis would make a nice salt-cured treat as well, and agreeing, andrew replied that the moth wings, which are lightly salted, pair better with a slightly acrid pickle. I remember him mentioning that just below the shelled chrysalis, the texture of pickled caterpillar in mid-transformation is very 'q' (a taiwanese designation for the texture of an object that first holds firm and then yields to applied pressure) though I do a disservice to his fine articulation of the actual components of the meal, which he described quite elegantly. we followed the meal with a generous pour of iced lapsong suchong, fresh ginger juice, and bourbon...and I awoke shortly after.

While he may sometimes haunt certain sections of lincoln heights, chavez ravine, and a variety of sundry and unspecified los angeles locales, clear infiltration of mental space has also been demonstrated...side effects are usually nutritional in both the gastronomic sense and in the larger sense of the nourishment of consciousness.

Fax: Godfrey looks hungry for percussion. Do you remember your first record/tape/CD?

AC: The first piece of music I ever purchased was the Beastie Boys 'Licensed to Ill' cassette. A friend of mine already had Run DMC's 'Raising Hell' so we decided it'd be best if I picked up the beasties release.

At this time in my life, I was 10 years old, and my dad was in the habit of waking me up on Saturday mornings and enthusiastically corraling me in front of the TV whenever his two favorite music videos came on: The Beastie Boys "Fight For Your Right To Party" and Twisted Sisters' "I Wanna Rock."

Because it was my dad, and his enthusiasm was embarrassing, I feigned lack of interest. But back with my friends in the neighborhood, we were busy memorizing every word on Licensed to Ill (starting with 'Paul Revere' of course), just like we had done to "Raising Hell" a little earlier.

Fax: When did you start writing about music critically? Is it at all related to your literary output?

AC: Let me start with the first piece I had published. Somehow or another a friend of a guy who was working at URB magazine knew I was into jazz/ free jazz/ improv and he put me in touch with their editor as they were looking for someone to write about "Innovators" in this area of music. I was allowed to pick three folks; I chose Eric Dolphy, Derek Bailey and Anthony Braxton (Sun Ra, John Coltrane and Ornette Coleman were already being covered.) That started a brief relationship wherein every time they wanted to do an article about something slightly jazzy or experimental (but still relevant to URB readers), they would call on me.

When I moved to Los Angeles (I had been in Chicago), I saw an Adam Rudolph concert and introduced myself to him and he asked if I'd be interested in writing about the show I just saw. He put me in touch with Signal to Noise, who wasn't interested in that particular article, ultimately, but who then put me in touch with Stuart Broomer, who was editing Coda at the time. So I started doing some regular CD/ live reviews for Coda, and, later down the road, for Signal to Noise also.

As far as when I ACTUALLY started writing about music, the first piece I did was for a high school assignment of some kind or another about the Sixties. I chose to write about Captain Beefheart's "Trout Mask Replica" as an example of un-psychedelic music that was nonetheless more in tune with actuality than the music typically associated with the era through cliche-ridden quasi-romantic pigeonhole-inducing nostalgia.

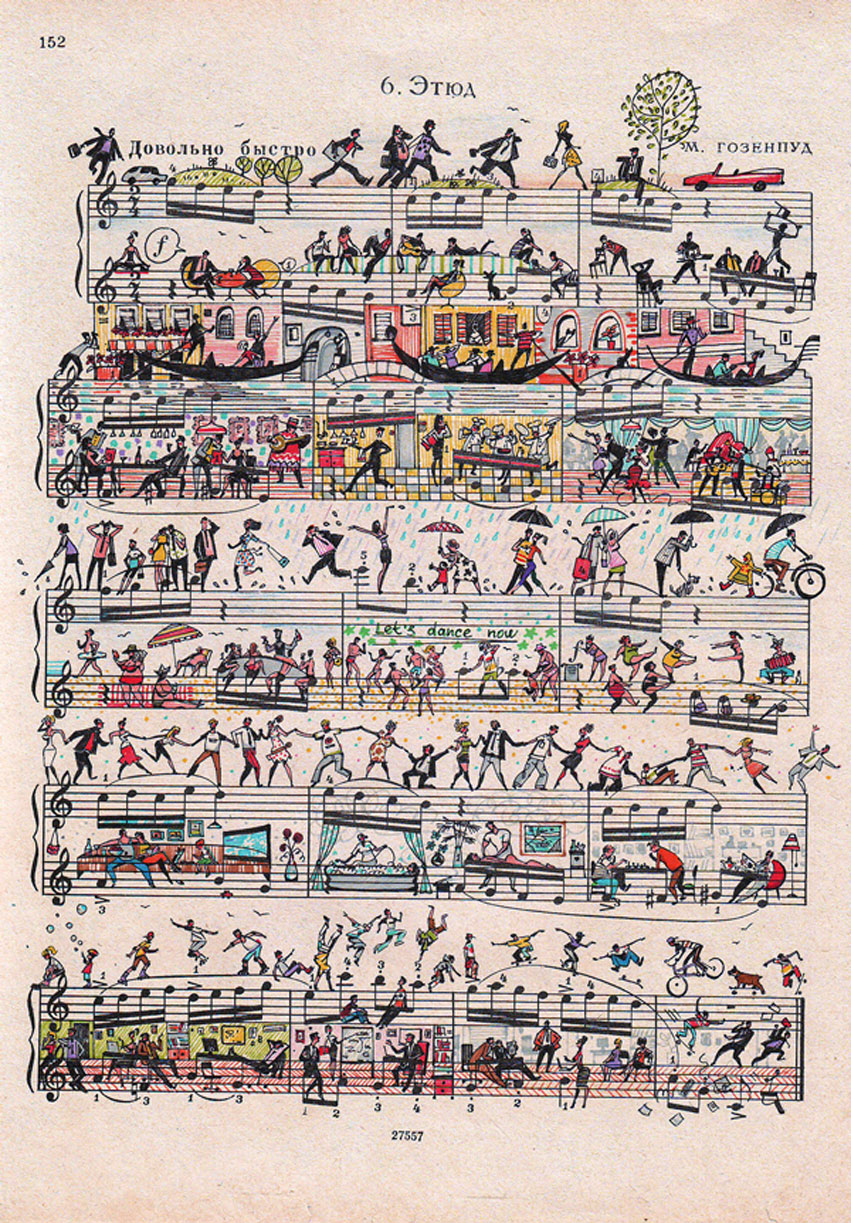

I also wrote my undergraduate thesis on philosophies of time in improvised music, attempting to separate the music from the naive notion that improvisation is always about the now now now of the unending present. I continue to write about improv and contemporary music because it is my opinion that these artists - more than any others - are creating ever-more-advanced works that creatively confront fundamental aesthetic, philosophical, spatial and temporal questions. While visual artists get the money, the press and the cultural standing, these musicians are deep at work, and going practically unrecognized. And by "practically" I mean barely surviving despite the enormous contributions they are making to the landscape of civilization.

Just to put this in a little context: I also write about fine art for several magazines. They pay me well. When I write about music, I get, if not zilch, a payment so paltry as to be more symbolic than renumerative. The same pattern holds for the musicians as well: they often lose money by accepting a gig out of town. And yet they are doing more important, more focussed and more rigorous work, in my opinion. The reason it needs to be written about is because their work needs to be understood in the entire context of the cultural and philosophical developments that other art forms apparently inherit automatically. This, despite some excellent recent scholarship in this area by Graham Locke, George Lewis and Mike Heffley. But there's a lot of work that needs to be done for the musicians, and for the sake of the music.

Fax: You've been known to possess a penchant for disc golf, have you ever thought about writing sports journalism?

AC: I actually wrote a piece about all the Aces (hole in ones) that I've thrown in disc golf - describing the situation, the flight, the disc, etc. It's about 3,000 words - I've had 15 aces. I haven't performed it yet, but I'm sure I'll stick it in a reading somewhere down the line.

If I were to write an essay about disc golf, I'd have to start with the baskets - they've got some fundamental design flaws. And yet, some of the one-off baskets I've seen people make on private courses function so much better.

For example, when I recently played in Budapest, we used a "homemade" basket that was designed to adhere pretty closely to the PDGA guidelines (see the second half of this article (PDF) to see what I'm talking about), yet the guys in Budapest made one crucial innovation that I've never seen on other baskets, and which, because it helps the device function so much better, I'm sure would be deemed 'outside of regulation.'

For a young sport with very DIY origins, it baffles my mind that 1) basket design isn't better and more functional and 2) that the PDGA is so rigidly anal about protecting the bad design and discouraging experimentation and innovation. (My theory, and it's pretty obvious when you think about it since every organization and regulatory body functions in this manner, is that the PDGA simply wants to appease the companies that are already manufacturing baskets: Innova, Discraft and DGA already have their equipment setup for the purpose of making these baskets, and the PDGA doesn't want to allow more and better designs to appear because these preexisting companies would either be left behind or have to alter their existing process/ equipment. And since these companies are the main source of funding for the PDGA, the PDGA isn't about to bite the hand that feeds it, so to speak.)

OK, that got away from me a little bit. I told you I had a rant about the subject. That's just the beginning of it; don't let me get started on the actual technical details involved and the history of the sport to consider.

As far as actual journalism about the sport, I will admit to having dreamed of a future where I could be the Vin Scully of disc golf: broadcasting pro tournaments, analyzing disc selection, route strategy, putting techniques, player bios, etc. For me, there is something incredibly compelling about a disc's flight in the air, and it doesn't seem impossible that I could translate the passion I have for the glide, the fade, the angle and the speed of a disc to a more general public. Shit, when I saw portraits of disc throwers on the ancient vases at the Getty Villa recently, I finally realized that disc sports are about as old as they come. For those who appreciate aesthetics as much as athletics, and vice versa, throwing a disc and controlling its flight can be one of life's supreme pleasures.

JR: One note on formally redefining baskets...Andrew and I were recently at a bar in cihangir that claims to operate the worlds first minidiscgolf putt-putt course. Because we had unknowingly stumbled into the joint on a bender, we were unprepared for the site that unfolded before our eyes...

Miniature hills of groomed spices, like a loaded donkey cart in a near eastern spice market, expanded onto the two acre course behind the main area of the bar. At the base of hole one , a watertrap of vinegar, chopped garlic, olive oil, anchovy paste, and cayenne pepper. We immediately knew we needed to try the course out, and asked the bartender in the 'clubhouse' if we could rent some discs. Since we didn't have any cash, I offered him one of Andrews records we'd been carrying along to play on his LP jukebox, some record with a gridded cover of tiny pictures depicting scantclothed, early seventies midriffs and asses on the streets, undoubtedly funky. The bartender obligingly gave us each a tequila shot and a pair of small putting discs made of meat, and sent us back to hole one.

Yeah, the discs were floppy and weird, and they still dripped uncooked meat juice, but my first shot whipped the air with a whirr, then skidded across the hill, kicking up coriander dust and flopping into a little pile of allspice. Andrew, a much stronger player, threw a line drive that looked to be a perfect ace. It tagged the front lip of the basket and spun off, a lurching plop into the marinade trap. When there's only one thing to possibly hit on the course, I have a tendency to misthrow my disc right into it, so my second shot careened straight into a column of salt that looked like a stack of salt licks. Andrew birdied with a burner right into the chains...the marinated meat disc sizzling immediately on the heated basket. I tossed another reckless putt that splattered in an olive oil puddle before bogeying with a decent curver that beckhambent in with another sizzle. As I approached the basket, I realized that the entire base was filled with charcoals that heated the mesh wire basket above and the metal chains. A pair of tongs hung from the side, which we used to peel the now cooked discs from the basket. A bogey never tasted so fine.

At hole two, a caddy named Colin who somehow knew Austin and Haoyan from high school, handed us two flat, thick slices of quince, carved perfectly as discs. The long straight shot ended in the corner, at a windmill. The blades of the windmill were spinning so fast you could barely see them, three or four layers deep, and the hole was right behind these blades. When we tossed the quince discs into the hole, the blades choppeded them into a stream of floating juice and pulp which landed in the cup behind the blades. Since we both birdied, Colin ran up with a little demibaguette and shut the windmill off, congratulatory. We dipped bread pieces into the cup, scooping up a perfect consistency of jam, and headed on. At hole three, we were given kimchi pancake discs which were tossed into a soy and vinegar tray with hanging squid tentacles acting as chains. The discs slammed into the chains and dropped into the tray, and the loose pieces of grilled squid fell onto the disc. Some chick came by in a cart with another tray full of soju, so we drank until it started to rain. The groundskeepers, bill murray-looking caddyshack types, quickly covered the course and play stopped...

We waited in the clubhouse for a longtime, hoping to resume the round. Since the bartender really dug that record, he kept pouring us homemade apricot brandy, and we talked about the course, which he designed. Apparently he too had gotten bored with disc golf orthodoxy and had decided to build the putt-putt course as an alternative. He designed every basket to uniquely suit the hole.

By now it was really late, so we gave this cat mad props and vowed to come back, but since we'd both gotten so drunk, we couldn't figure out where the joint was the next day...wish i could ask that kid Colin, but haven't been able to find him either. But I'm sue we'll come across it again some night, inshallah...

Fax: In 2006, a collection of your writing was published in "Langquage Makes Plastic of the Body". What inspired your title and how do you approach publishing vs. performing?

AC: I wrote down the phrase that became the title for the book one night when I was playing around with alphabet stickers and stencils. I had been thinking about the give and take between the physicality I experience when encountering language/letters and was trying to work through some things. The phrase clarified a lot for me, and made sense as a title since, first, language does make plastic of the body, and, second, what is inside the book is often me making language plastic as a response/reflection of what it does to the body.

The "q" in 'langquage' from the title is also my attempt to visually and physically enact and give form to this uber-quasi-spiral.

The entire title, by itself, succintly addresses and investigates the endless chain reaction at stake/work.

As far as how I approach the difference between publishing and performing, it's an ongoing process. I never realized I could be a performer (or writer - of the kinds of things I want to read -, for that matter) until Jen Hofer asked me to read in "The Moving Word" series of poets and filmmakers she was curating in her backyard in 2006. Since I had nothing to read and had been not only bored but either put to sleep or semi-infuriated by 90% of the readings I had attended, I decided to attempt to write the kinds of pieces that I would enjoy hearing live. It also meant reading my writing live for the first time. So I came up with some things, really enjoyed the performance, and was asked by Jane Sprague, who was in attendance, to put together a book for her Palm Press imprint.

Partly because there was a visual element to this performance (and subsequent "early" performances by me), Jane suggested the possibility of doing a DVD. Keeping in mind my instinctual wariness when it comes to readings, I thought that a DVD of a poetry reading might not be quite as exciting as it sounds (ha!). Not only that, I have an instinctual bias against the predominance of visual culture in our lives, and didn't want to submit language and sounds to its nefarious embrace.

What Jane and I agreed on, though, was that a CD documenting how I read some of the work would be nice. In addition, this ended up giving me room to include things on the CD that wouldn't fit in the confines of a 40 page chapbook. In the end, I structured the relationship so that 1/3 of the book and CD overlap.

Well, that little bit of history is all very well and good you might be saying, but what of the relationship between performing and publishing you're still wondering. Well, one thing I came to realize while working on the CD and doing readings from it after the book came out is how much I enjoy performing, and writing for performance. And since I have a lot more offers to do readings than I do to publish books, I started writing pieces specifically for performance. A dilemma I found is that pieces of my writing that I really liked are not so suitable for the context of performance. I tried reading them anyway, but audiences usually shuffle uncomfortably during those sections - something I don't really mind, in all honesty. But one issue I now have is this: I'm so attached to the performance of some pieces that as I try and put a book together (I'm working on a manuscript now for Writ Large Press) that without a recording, something fundamental seems to be missing.

So let's just say that, right now, it's an unresolved but fruitful tension in my work.

Fax: Do you find tension an inherit/common ingredient for creativity?

AC: Tension is often present in my creative process. I never start from a tabula rasa when I do work; something always stimulates me. When I get ruffled by something, I almost always try and explore it, and while that's not what I would consider a positive stimulus, these rufflings often help me clarify my own vision of what is "good" or "worthwhile", present or absent or confronted/ confrontable in my own work.

I try to follow the stimulus, push it around a bit - both inside me and in an external form - and see what happens. But it often takes time - sometimes years - to think about things and work with them before I can recognize the specific tension, usually inside myself, that keeps me interested in a subject/ stimulus. There are pieces that I've written and published that I still don't know how I feel about - not in terms of good or bad, or like or dislike, but in the sense that I can't say exactly what is going on or what viewpoint the piece is creating. And I would consider those pieces among my most successful - precisely because they offer people, including myself, the chance to grapple with and triangulate the relationship between self, environment and perspective.

Once you externalize something, it has a life of its own.

If I write something and read back over it the same way every time, I know I'm usually not that interested in what is going on. But if I write something that gives me pause when I read it, that makes me ask questions of it and of myself for writing it, then I know that a potentially fruitful tension and dynamic is at work. A good stimulus should create a refracted and fractalized domino-effect of other stimuli.

One tension in effect when even thinking about work in this way is the fact that we live in environments that are hyperstimulated with media. The problem that raises for consciousness and how we hone our consciousness is that we're undernourished in non-media-diven stimulus, and often can't recognize the beautiful presences right in our midst. We're not used to - and not encouraged to think of or recognize - stimuli that aren't contained in packages, whether they're books, downloads, pictures hanging on a wall, etc.

So for me, as someone who generates media, the potentially paradoxical question becomes: how can I generate media that is itself stimulating, and that also stimulates a practice of reading and more deeply interacting with the world, the unmediated world?

It's a tension.

Fax: In your mind, how important is the role of language in our representation of reality and expression of consciousness?

AC: Language is simply one medium among others; I don't give it, or any medium, more respect, primacy or importance than any other.

When I was an undergraduate I got into a discussion with a professor about the fact that it makes no sense, from my perspective, to have language be the only medium used to evaluate the transmission of information and understanding. I don't think writing a paper is always the best way to represent a critical engagement with information. Sometimes creating audio, or a picture or an event, etc. might more accurately and adequately probe the material under review.

As far as representations of reality and expressions of consciousness, we have five senses, and language isn't one of them. It might be a tool that helps us engage with these senses as they confront representations, expressions and the action of creating representations and expressions, but it is just a tool. To think that all of consciousness or experience can be encompassed within the linguistic realm is fallacious.

This isn't to say that I don't value the illuminations and interactions available to language when it approaches other mediums. I do. I've met many artists who feel that language either has no place interacting with other arts or who feel that language is always already inadequate to deal with other arts. The latter perspective, to me, is a semi-natural reaction to the fact that language is often viewed as the sole medium capable of dealing with the other arts. But that perspective itself is what needs to be eradicated: let language do its thing, let other mediums do theirs. There is no hierarchy.

The fact that many people use language as an entryway into other works is simply because it is more readily available. But don't conflate availability with ease of use or definitivity.

There are two issues with language in relation to the representation of reality/ expression of consciousness we're talking about: its critical capabilities and its creative abilities. I don't think anyone would argue that the creative use of language makes it simply one medium among others. But a fundamental problematic emerges if we adopt the perspective that language should be the de facto medium used to think critically about other work. Other mediums offer other critical entrypoints. The idea that "when we think, we think in language" I completely disagree with. There is no linguistic basis for thought. When we think, we think. Period. Critical, creative and analytical thinking can happen in any medium.

The brain processes stimulus, and the way it processes is not necessarily via linguistics.

You might think that because I don't believe in language as the natural medium for critical thinking, that I have something against critics who use it. Not at all. I lose respect for artists who dismiss them; it's like these artists don't want anyone to think about their work. Critics are an easy target because their craft is, generally speaking, practiced so poorly, but that doesn't mean that it's not an important practice. Oscar Wilde's essay on "The Critic As Artist" should be required reading for any artist who takes their craft seriously.

Fax: Any speculations about human beings' spacefaring endeavors away from our spaceship Earth?

AC: I think some of us already voyage beyond earth. There are non-earth-based frequencies that rare beings are able to tune into and tap.

Not that earth and humanity should be dismissed, but the practically monovisioned focus on humans and earthly existence gets tired. I'm not advocating more interest in or investigation of religion, but instead on biology, energy and the flows between. It would be a radical, juvenile mistake to think that other kinds of biology are not at work across galaxies. And just because we're human, and happen to be on this planet, doesn't mean that we aren't or can't be affected by these other flows.

The relentless narcissism that humans project onto other beings is evidenced by the ubiquitous and inane question "Is there life on Mars?" It's a planet, a rock: the thing itself is alive. It takes a very narrow understanding of what life is not to recognize that.

As far as traveling to other planets, etc., I don't think we actually need to go to other planets in order to experience them. And I'm not referencing out-of-body experiences either. Just the fact alone that you have a body on this planet makes it possible that you can connect with things happening on other planets. You simply have to be attuned to the frequencies.

Fax: Do these frequencies ever take forms perceivable by human senses?

AC: Well, if we are strictly talking about the five recognized individual senses, I don't think so. But sometimes senses work together, and I'm not just referring to synesthesia (which certainly is a case of special attunement.) Two senses can work together or a sense can work in tandem with a desire for example. When you layer consciousness and objectively verifiable action with unconsciousness and uncontrollable forces, you are often in the presence of these frequencies. But just because they are around and inside you doesn't mean they are perceivable by you or by one of your senses.

These frequencies are recognized within consciousness but without its aid: you can't seek them out.

Another way of looking at your question would focus on the question of how/ when/ etc. these frequencies "surface in forms." If conscious perception is a solid and the unconscious is a liquid, these frequencies are a gas. And when they surface, they surface gaslike. The entire spectrum between visibility and invisibility is in play. Imagine corresponding spectrums for all the other senses.

Let me give you two examples of socially/ culturally acceptable ways to admit recognition of these frequencies: intuition and momentum. When athletes, sports analysts and broadcasters discuss momentum, they do so in such a way as to shroud it in mysticism, arationality and magic. Considering the social and economic importance we place on sports - it's a regular feature of the news and a multi-trillion dollar worldwide industry etc. - there is a delightful irony in the fact that it so often gets boiled down to something as intangible as momentum.

While athletics and therefore momentum are often coded masculine, the concept of intuition has been coded feminine. Folks who otherwise would be reluctant to recognize the presence of supernatural forces/ non-earthly frequencies seem to have no problem using these terms.

Fax: As a well-respected connoisseur of fine foods & spirits, what is your ideal meal like these days?

AC: Let me tell you about one fantastic meal I had while travelling recently. The cellist Albert Márkos invited me to join he, his wife and Szilárd Mezei for dinner at his home in Budapest. We started the evening with a nice cup of ouzo his wife had brought back from Greece, some cheeses - I liked the herby goat one - and some red wine. Then Albert brought out his improvised and embellished version of moussaka. He had shaved potatoes on the bottom, ground beef on top of that, then peas, then roasted tomatoes and red peppers on top of it all. He had cooked the potatoes, the peas and the meat all separately, with different formations of seasonings, and then put them together and added the red veggies on top. Unbelievably delicious.

Szilárd also gave me a bottle of homemade apricot brandy that is pretty much the best hard alcohol I've ever had. The intensity of the fruit taste is so strong it seeps into your gums and into your mouth in rivulets of flavor that the alcohol opens up. The scent is pure apricot - not apricot essence or oil: just apricot. It is an exceptional apéritif or digestif. I'm drinking it very sparingly so I can share it with as many people as possible. You'll taste it when you come to town!

Another thing I really enjoyed about my meals while traveling was the presence of small bowls of soup to start a meal - usually a thin, clear, well-flavored broth with vermicelli noodles and a small amount of diced vegetables. I really appreciate, even for non-fancy meals, having courses. It emphasizes the time that should be taken and honored when eating. It's about pacing. Flavors and textures over time. Even if only just two "courses," like a soup and an entree. A duration is involved. Let the mouth be played (with) by the food.