Facsimile Magazine, Published by Haoyan of America. Volume Three, Number Eleven, 2009. ISSN 1937-2116.

Facsimile Magazine, Published by Haoyan of America. Volume Three, Number Eleven, 2009. ISSN 1937-2116.

Festival Review & Photography by Andrew Choate

Ostrava is a former coal-mining town in the Czech Republic that is in the process of reinventing itself after its Vítkovice factory - one of the largest industrial complexes in all of Europe - closed in 1998. The Ostrava Days New Music festival, which takes place every two years and occurred for the fifth time in 2009, is one of the brightest and most stimulating ways this reinvention is being incarnated.

Sweet Vítkovice steel

For anyone who is a fan of Bernd and Hilla Becher's photographic oeuvre documenting the forms involved in modern industrial landscapes, Vítkovice is a treasure. (In fact, the site has applied for UNESCO World Heritage status, and has already received the European equivalent.) It was fitting that the first concert to open this year's festival was held in the former blast furnace of the Vítkovice steel mill. The audience was treated to eight compositions by Phil Niblock accompanied by dual projections of his films, totaling almost five hours of music. An incredible humming roar was audible immediately upon entering the factory, combined with the pervasive smell of iron, steel and large, heavy machinery gathering dust.

Niblock has designed his music to be heard at loud volumes, the better to experience the pulses and beats created by overlapping harmonics from "24-track digitally-processed monolithic microtonal drones," as Niblock describes his own work.

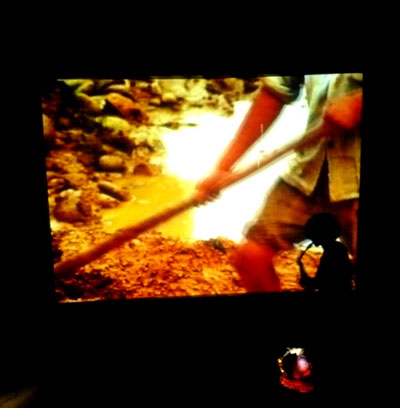

Hearing his music in a place with such enormous spatial volume only contributed to the effect of gargantuan physicality. The films that were projected were filmed by Niblock in the 1960s and 70s and focus on the actions of people in rural settings working: fishing, weaving, cooking, digging, hammering, laying bricks, cutting noodles, planting garlic, etc. The films are not "synced" to the music: the films simply start playing and don't stop until the music is over, when they are shut off. There are therefore no overt links between the sounds and the images.

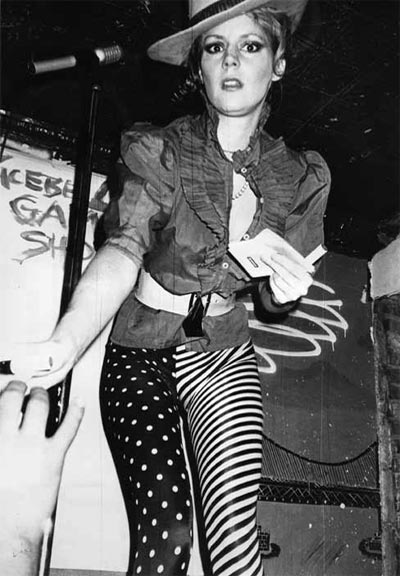

The first hour was filmless, with a pre-recorded track playing back as the audience wandered the multi-tiered space and got acquainted with industrial-sized bolts, winches, turbines, etc. The official concert began with "Sax Mix" (2004) and the turning on of the projectors. Eighty-five channels of pre-recorded and mixed alto, tenor and baritone sax drone were augmented by live saxophone perambulations around and in front of the projection screens by David Kant, Lucie Možna and Lucie Páchová.

Sax shadow per Niblock

After a couple more compositions, which flowed pretty seamlessly from one to another, with barely - if any - clapping in-between, baritone vocalist Thomas Buckner took to the stage for "AYU Live" (1999). By this time, after a couple hours of listening, I realized that my favorite parts of these works were the beginnings and ends, because you could hear the layers of multi-tracked channels dissolve or accrete and hear the beautiful fluttering of the individual overtones. Also, partly because of the overwhelming density of the sounds, the lack of music when a piece ended really sounded great, like the sense of hearing had been awoken. Kind of funny since Niblock's music could easily be mistaken for an alarm: an industrial-sized alarm signaling an industrial-sized accident.

Almost immediately after Buckner started singing, the tape began and I started questioning the necessity or value of having live performers when the pre-recorded stuff is so clearly going to dominate, decibelly, their output. As if on cue to answer my skepticism, occasional moments of Gregorian grandeur emerged when a phrase of Buckner's serendipitously synced with a phase of the tape. I also really enjoyed the simple contrast in timbre between the recorded samples and the live cello of Andrej Gál in "Poure" (2008) and Nikolaus Schlierf's viola in "Valence" (2005). The decision to experiment with different placements of performers around the factory for each composition proved especially successful as it was quite dark inside and new sound sources kept popping up and surprising the ears. The irruption of an acoustic instrument had a way of shattering the digitality of the recordings, making me feel like a bat with suddenly new bearings each time.

Probably because the one-dimensionality of the droning recorded samples was failing to keep me completely enamored or engaged after three hours, "Tow by Tom", a 2005 piece for two orchestras (and no tape), conducted by festival director Petr Kotík, stood out tremendously. The swirl of acoustic instruments sounded absolutely lush in contrast to so much digitally processed swathing. But it wasn't a mellow, easygoing lushness; it was more threatening, the way a jungle's teeming vegetation both signals and hides something ominous lurking within, nearby.

Before I move on to the second day of the festival, something needs to be said about the film component of Niblock's work. According to his website, his musical compositions "giv[e] a poetic dignity to sheer grueling slog." Indeed, he is filming a lot of very difficult labor, but his description of what the music does does not characterize how I've felt during his performances. In fact, it is precisely the addition of the music that turns the images of poor people laboring in the Global South into rather uncomfortable exoticizations of people and the things they do in far away places. That's clearly not his intention, and on some level he must respect the people he's filming, but there is an exploitative element when you characterize the work of others as "grueling slog," make the assumption that the work itself does not have "poetic dignity," and then proceed to give yourself and your music the power to provide and bestow this heretofore elusive dignity. The films alone are quite engaging and compelling as indexical, rhythmic studies of human activity, similar to Muybridge's photographs, the Qatsi trilogy or Baraka (though predating the films, with much more of a patient, inquisitive eye, and without the heavy-handed use of time lapses.) I honestly still don't know exactly how I feel about how Niblock's films and music work together, but there is a tension at work between them that has been discomfiting and unresolved since I first experienced them together almost a decade ago.

The second day of the festival was a marathon of 13 electronic music acts that took place in the city's large contemporary art gallery; it lasted from two in the afternoon until midnight.

Gallery art

Czech DJ Radan Just, as Decolective, broke the ice with a digital parade of live-mixed sample playback. His chosen tones sounded like synthesized bass-clarinet octave blurs à la Wolfgang Fuchs layered with thin, shifting beats constructed out of string sounds. While the playfulness of the highly digitized rhythms forged a balance between the abrasive and the cheesy, there was just enough edge to each tone to bring out a carnality in the music. About halfway through the set, drum sounds were incorporated into the mix. Considering that all of the other sounds were already being patterned rhythmically to begin with, the introduction of actual drum samples was unnecessary. Thankfully, he showed he was willing to extinguish the major backbeats of any given rhythmic cycle and instead let the silence imply the downbeat. It felt like sonic rugmaking, with a warp and weft of multiple layers and beats.

Local Ostrava band Sklo made an impression before they played a note. Dozens of objects were arranged on the table in front of the performers: a metal framed Erector-set type thing with a rock at the top, pipes, bowls, springs, hoses, etc.

Skol

Using found objects rescued from the trash, Noah Purifoy-like, they constructed an improvisation based on the energy, and ultimate entropy, of quotidian materials amplified through effects processors, mixers and a scraped guitar.

All three performers were extremely active while playing, moving briskly from Tuvan throat distortion to heavily reverbed spring-shaking and the electrification of a pepper grinder. Voice Crack as a garage band.

Sklo was followed by a four-speaker surround-sound electro-acoustic composition by Michal Rataj called "Machine - Hand - Mind - Memory." Using a hacked Wii controller, Rataj pushed and pulled huge washes of crisp electro-acoustic bursts across the field of sound. These INA-GRM-like crystalline spectral breakdowns were layered with samples of graphite writing on wood, combining a real sensitivity to the timbral quality of electronic sounds with an equal emphasis on gesture in performance. Moments of quiet crackling that could have been either graphite or electronics captured the complexity of relations between memories of handwriting on desks and the new kinds of handwriting that technology makes possible, changing the future of how and what memories will form. The deep intelligence behind the conception of this piece and the great aesthetic pleasure involved in listening to it bespeak volumes about the potential of this 34 year old composer.

Rataj in action

Next was a duet between the Czech conceptual improvisor and sonic miniaturist Ivan Palacký (Carpets Curtains) and Peter Graham. I was in the back and couldn't see the stage so well, and heard what I thought was fingers playing on a pillow. I liked the image of a finger-pillow: a place where the fingers go to rest a bit. I found out later that Palacký was playing an amplified knitting machine. This morphed into a low synthy rumble and tiny flutters of keys from Graham's keyboard. This was music that slithered over the ground like a piece of paper that the wind won't let come to rest.

The three members of Napalmed listed their instruments as "imagination," "feelings," and "energy." It was noise, good noise, in the classic get-it-all-out visceral-exposition style.

The audience responded enthusiastically to the flourishing display of screamed and sweated emotions. Distortion, amplification and feedback are simply the means to those ends. Part of me wonders why audiences embrace such willfully wild displays of torment and edge-of-the-abyss type strife; it seems like people think these emotions are somehow truer and therefore more honest and believable than any others. Or maybe it's just the most appropriately cathartic relief from the troubling times within and around. The noise genre does a great job devising endless permutations of ways to express a fundamental and yet strangely hidden and unpinpointable facet of the human experience: "I FEEL!" Napalmed's set gave momentum to this implied proclamation and received full attention in return.

This event really was a marathon and at this point I had to take a break to eat and let my body absorb all the music I had already ingested. When I came out of the gallery, it was drizzling. As I approached the main street I needed to cross in order to get to my hotel, I came across a startlingly bizarre scene: dozens and dozens of red Ferraris and yellow Lamborghinis were coming around the corner and filling the street. Soon, the entire road was chock full of these high-end cars idling and revving their engines as they waited for the traffic that they were causing to clear. All were grouped according to manufacturer: there went the Ferraris, then the Lamborghinis, then the Mercedes, the BMWs, etc.. After so much uncommon and adventurous music, it was disorienting to suddenly be confronted with a stream of extremely expensive, totally worthless icons of mechanical materialism.

Proof, the next morning, that it wasn't a mirage.

After a rest and some turkey and bread dumplings, I was back at the gallery. Boot was the first act of three who incorporated live video mixing into their set. In fact, it was the variety of visual information and video techniques on display that held my attention more than the music: black and white stills, painterly heat-sensitive splotchings, architectural room renderings, vortices careening in hyperbolic space, clips from Nosferatu, a nineteen-eighties robot documentary and, my favorite, a kind of disco Chiapet protruding needles of multiplying and blinking light. The sounds that accompany this dazzling are "the result of computer-generated information relevant to visible data flow." I think that means that what's onscreen determines the music, and it was clear that the sounds were a bit of an afterthought (or non-thought once whatever processing algorithm they wrote to translate the visual data into sonic form was finished.) It was perfectly acceptable background to the assorted visuals: ambient fragmentary electronica.

Andrés G. Jankowski, as 1605munro, performed a moody, episodic set that shifted in discrete, practically modular sections. Soft, synthesized droney tones with occasional click-ribbits gave way to jazzy drum samples, then super-reverbed percussion à la This Heat, finishing with MOR drum 'n' bass. I listened to most of this set while lying flat on my back and looking at the reflection of the video in the ceiling, seeing spooky black shapeshifting and the murdering of glossy surfaces.

BlackHole-Factory is a German audiovisual/performance collective that serves as the umbrella for over sixteen different projects that its three members work within. Restmetall focusses on using found objects to create both the sound and the visuals for a real-time live-animation mix-down crunchtogether. Everything is created and transformed during the performance: you see a sound made, hear it, then hear a refraction of it; you see Elke Utermoehler put her hands on the table under the video camera, then take them off, yet there they remain onscreen. Simple overlappings of remembered events and live actions created rich disjunctions for the mind to munch on. At one point, an image of Elke's hand appeared amid grainy layers of yellow and green light on the screen. With her fingers pointed down and cut off at the wrist, the fingers jumped up from the surface in what looked like a birdfoot dance with alien gang-signs. It was nice to see her and her partner-in-performance, Martin Kroll, smiling during the set, clearly enjoying themselves in the process of making what many folks consider dry abstraction. 'Difficult' music is fun! Kroll looked like a combination between the Harold Ramis of Ghostbusters and Moe from The Simpsons, and even shared a similar kind of joint M.O. — serving up futuristic cocktails to transport beings from one dimension to another. If you're familiar with the outstanding real-time video work of Carole Kim, Restmetall shares that kind of sensibility.

The last set of this marathon of electronic music featured Double Affair, a dancey glitch plus guitar samplefest. Hard drum breaks and melodic beeps similar to those on Latryx's "Say That" were layered with live violin playing from Peter Krajniak, current director of the Janáček Philharmonic.

The part of the Ostrava Days festival I attended is the culmination of a three week residency wherein "students" - primarily PhD candidates, post-docs and young teachers - from around the world come to attend workshops and rehearsals with the most enthusiastic New Music composers, performers and conductors available anywhere. Everyone involved in the festival is given meal tickets to eat together at one restaurant for lunch and another for dinner. This relaxed, communal atmosphere provides valuable opportunities, twice a day, to meet and converse with other artists without any of the implied intellectual hierarchy that is unavoidable during rehearsals. The director of Ostrava Days - flutist, conductor and composer Petr Kotik - was explicit to me about this: if there's one lesson to be learned from the Black Mountain College experiment, it's that the most important discussions and creative developments occur when students and teachers, older and younger artists, performers and composers, conductors and critics all meet on the same footing, around a shared meal table.

Janáček Philharmonic (Rotate head 90 degrees right)

The emphasis placed on performing the students' works was highlighted when the first piece played at the Philharmonic Hall was "Fanfares Procession" by the 26 year old Polish composer Jacub Palczyk. I didn't think it was as refined as many of the student pieces that followed it over the course of the next several days, but the smattering of flutes and percussion was quite pleasant, and the tuba playing of Šín Karel was intrepid and decorous. Morton Feldman's "Flute and Orchestra" from 1977-78 followed, with Peter Rundel conducting the Janáček Philharmonic and Petr Kotik as the featured flutist. Feldman's compositions seem to fade in from the ether and disappear just as nonchalantly, and this piece was no exception. As each section of the orchestra stopped and started, the decay was ravishingly lovely. I loved watching the sounds emanate from the movements of Rundel's left hand, appearing and dissolving with so much graceful authority. Tiny, tinkling percussion - like flicking a flimsy stick - gave time a hefty presence. And not just time, but the time of waiting, anticipating; unpredictable repercussions. To hear a sound act like an object falling down out of space, but instead of hearing it land, you hear the stars above it rattling in reaction. The years that have been devoted to New Music by both Kotik and Rundel - over 50 between them - were clearly in evidence throughout the duration of this performance, especially as the piece eased into its cello and flute coda, to wait patiently for wherever it will emerge again.

There were several concerts during this festival that began sounding so great so immediately that all I could do was listen and absorb the music. This Feldman piece was one of those. Not only is the piece rarely performed - even Christian Wolff, who was in attendance, had never heard it performed before - but it exerts a pull on the ears that is at once inviting and questioning.

The performance of British composer Richard Ayres' "No. 30 NONcerto for orchestra, cello and high soprano" (2003) was conducted by Roland Kluttig. While grunting, the cello player, Andrej Gál, was required to thrust his bow, almost spasmodically, at the strings. An element of frustration and failure was palpable, and part of the score. The audience responded with laughter - uncomfortable, sympathetic and amused laughter, tangled. There seemed to be a Bugs Bunny vs. Elmer Fudd dynamic between the cello and Claire Wild's high soprano: she, clear-pitched and merrily going about her song; he, embarrassed and foiled at every turn. (I'm referring only to the score, not the quality of the performances, which were stellar and dramatic.)

Wild sang the notes like she was taking a bite out of something: all snap.

In the second movement, she sang like she was peering through a peephole: hiding, but expressing the hiding. Gál strummed the cello with his fingernails. Branches with leaves attached appeared in the brass section before the end of the piece and were shaken and rustled above the players' heads. The piece ended on a huge, bombastic orchestral crescendo, "like the falling of a bomb," in Ayres' words. This catastrophic ending, in combination with the extended techniques of the cellist and the swishing branches, made the piece feel like a parody of the extremes that many new music composers utilize in order to achieve and investigate new sounds.

Phosphor (Rotate head 90 degrees right)

The fourth day began with afternoon concerts devoted to "Computers in Composition" and took place amid the beautiful acoustics of the Janáček Conservatory's auditorium. Phosphor, the Berlin-based electro-acoustic improv septet, opened the concert with a performance of Michael Schumacher's "Isorhythmic Variations" (2009). Unusually for this ensemble, they seemed less concerned with the overall sound they were creating, and more intent on hitting the timed cues triggered by the laptop screen at the center of the stage. The individual sounds - in particular the glossolalic whimperings from Andrea Neumann and Axel Dörner's capsizing-robot bird-calls - were all marvelously crafted, but the performers appeared isolated by the strictures of the composition. Their performance of Samuel Sfirri's "For Callum Innes" (2009) fared better, with a real focus on lettings sounds have a beginning, middle and end. Ignaz Schick let out a small, frying whizz, guitarist Michael Renkel picked it up, twisted and re-pitched it and percussionist Burkhard Beins and tuba player Robin Hayward polished it, added serifs and put it away. Then it started again, same order, just a couple new small tweaks, with other players beginning to contribute. A distinctly organic rhythm was created through a splintering yet circular chain reaction.

A quote from a review in The Wire was reprinted in the Ostrava Days book to describe this band: "Phosphor have produced some remarkable ensemble sound." I find it hilarious that calling sounds "remarkable" passes for a description. So many advances are being made in modern music, yet we are so sorely lacking in intellectual and philosophical contextualizations of the work that critics can get away with simply calling it "remarkable." Unbelievable. The way Phosphor transforms sounds, individually and collectively, and rethinks the function of time in relation to sound is worthy of a treatise.

Their final set was a collective improvisation. Many of the composers and New Music aficionados I talked with about this set said they enjoyed it, but were disenchanted by the fact that it seemingly could have gone on forever, as if the ability to make interesting music, potentially ad infinitum, was a flaw. I loved it, but I'm also a lover of improvisation in general and of these musicians, in all the permutations they play in, individually. This set was more active than their recent Potlatch CD, Phosphor II, and I couldn't help but notice that, despite their stated focus to investigate new dynamics within improvisation, the traditional free jazz form wherein waves of activity build and subside was still at play.

The second set of the afternoon began with Lejaren HIller's "Sonata No. 3 for Violin and Piano" (1971). The 1st movement had nice piano tone clusters, played by the gifted Joseph Kubera. The combination of the violin and the piano was surprisingly disjunctive, with lots of staccato bumps. The 2nd movement featured a slow, dampened piano, with big mallet attacks on the low strings and grainy violin scratches clicked and plucked by Conrad Harris. And the 3rd movement was pure frolic. There were so many compositions performed over the course of this festival, and in such close proximity, that I can't remember each one with vivid clarity. So some I skip entirely in this recap. And on others, I'm trusting my notes. Like on this Hiller piece.

Peter Graham's "A Nap (Funeral Music for Mauricio Kagel)" (2009) featured Daan Vandewalle on piano, Daniel Skála on cymbalom and Ivan Palacký and Jaroslav Šťastný on electronics.

Jaroslav Šťastný is Peter Graham. He was forced to change his name as far as his composing goes because the Czech Performing Rights Association already had a Jaroslav Pokorný, which was his name at the time of the request. Then, after creating the alias, he married a woman whose last name meant happy (Šťastný) and in order to prevent her friends from joking that she was no longer happy after her marriage, he took her name. Genius comes in many flavors.

The piano and cymbalom created a very warm lullaby environment, with Vandewalle's gentle touch exuding soporific sweetness. The electronic musicians were placed at the back of the stage, intruding into the proceedings in scattered bursts of fuzzy gurgles. The title of the piece references napping as a kind of death, and it did put me to sleep for a moment, but not because it was deathly boring; on the contrary, it was just so soothing.

The concerts in the evening were in the large Janáček Philharmonic Hall. This was the first of two concert-length performances by the Ostravská Banda, a chamber orchestra that acts like a sort of international house band for the festival. They opened with Charles Ives' "The Unanswered Question" (1906/ 30). Per the composition notes, all the strings were outside the hall, the trumpet was in the balcony and the flutes were centered. The strings don't change tempo for the entire composition, and they didn't have to they were so fucking beautiful. Like still water on a gorgeous lake at dawn. The trumpet in the balcony was like a soft light shining down and the flutes shimmered like dewy foliage. Sorry for all the analogies, but the piece evoked a very specific scene. Ondřej Vrabec, the Ostravská Banda's conductor, was responsible for the strings, and he brought out an immense clarity and depth in their playing that I have not heard matched on any recordings of this piece. Petr Kotik conducted the rest, and turned the distance between ensemble members into music with a unity of purpose.

Ravi Kitappa's "singularities" (2008) possessed a certain verticality, with overlapping ups and downs of notes arcing vertiginously and discharging sparkles at surprising intervals. It reminded me of a less disorienting "For Ann (rising)" by James Tenney.

Hana Kotkova, photo by António Pedro Nobre

The biggest discovery I made during the festival was the music of Czech violinist Hana Kotkova during Wolfgang Rihm's "Gesungen Zeit." The sound of her violin was so instantly sonically mesmerizing that it made me think I had never heard a violin before, and yet it also made me feel that I understood the entire history of the instrument through her playing. Her tone had a rich warmth that made it stand out in complete relief against the percussion, piccolo, flute, clarinet, harp and other strings in the chamber orchestra. This play between the violin and the ensemble is also part of the composition, but even in the 2nd movement, when lines are tangled and reflected, Kotkova's violin was distinct and radiant. She could make the sound huge and galloping or tiny and sharp, as light as a spider itching its leg. The tonal quality was so exquisite that the category of the beautiful no longer seemed relevant: this was music beyond beauty: primal, galactic, entrancing.

The only adequate comparison I can make to how hearing her play live affected me is the time when I first heard and saw drummer Paul Lovens perform in 1996. Briefly, the first time I saw Lovens play was in an improv duet with saxophonist Evan Parker, whose music I loved and was feverishly anticipating hearing live for the first time. But when they came onstage and started playing, all of my attention immediately turned to Lovens: I had never seen or heard anything like the music he was making before me. (Even Parker must have been taken aback, because after only two minutes, he stepped back and let Lovens solo.) Ever since that concert, I have had an unparalleled regard for Mr. Lovens' music, and now I feel the same about Ms. Kotkova's playing. Both of these musicians have taught me things not only about what music is capable of, but, philosophically, how the body functions in time, amid stimulus, thought and the actions of other bodies.

The afternoon concerts on the fifth day were performed by the Quasars Ensemble, a chamber group from Slovakia devoted to contemporary music. Their first piece was Salvatore Sciarrino's "Quintettino No. 1" (1976), a composition for string quartet and clarinet. Low, barely-played-but-held-long clarinet tones gave wonderful depth to the screechy bowing of the strings. Like a mini Dumitrescu piece with the blackness of the night skidding over crushed shadows.

The world premiere of 27 year old Polish composer Karol Nepalski's "Trio of Forgotten Senses" (2007) was another example of how refined and exciting some of the student works were. It was composed for flute, violin and piano: the piano, played carefully yet charged by Diana Cibuĺová, was lightly prepared and the flute was played in such a way that it took on more of the character of Native American than concert hall flutistry. In the composition notes for the piece, Nepalski talks about inspiration from Eastern music, and the attempt to create a "transcultural" work. At one point near the end Andrea Bošková, the flutist, stood up, thrust forward and swung an armful of leaves into the air in front of her. She gave herself so completely to this act that it became a gorgeous and powerful flourish. It could have been silly, but it was performed with such confidence that it became a wonderfully successful, transporting gesture, bringing elements beyond music into play and into relation with music. The sounds of these leaves hitting the ground also made sense with what had come previously in the composition: buzzing, sighing and spitting poofs of breath through the flute, pinky plucking of the violin and soft mallet tapping on the piano strings. A mature composition by a young composer pursuing a unique path of exploration in his art.

Vítkovice flowers

Another revelatory moment of the festival was about to occur. I had never heard any of Gérard Grisey's compositions before, but ever since the Quasars Ensemble introduced me to the 1st movement of "Vortex Temporum," on this night, I have been avidly investigating his music. My initial reaction when they started to play this piece, a composition for five instruments and piano, was complete jaw-dropping awe. It begins with a clarinet and flute explosion that dissipates quickly and in bizarre rhythmic fashion, like the tempo is determined by sound bouncing off of the walls and corners of a dynamic polygon. Or think of a feather sinking in air, then suddenly swept up by some new current and sped up, now zipping in space with the force of a proton blast. A whirlwind where the flute and clarinet pass through fields of time, all under different pressure, not just speeding up and slowing down but cascading. I looked at the score after the performance and it starts in 4/4, then 13/16, 12/16, 9/16, 15/16, 4/4, 17/16, 14/16 etc. The piano also takes up the lines that the clarinet and flute start out playing, and the 1st movement ends in a bang-filled recapitulatory swirl.

I've listened to this piece a lot since this first exposure - in fact, I made it the ringtone on my phone - but that doesn't make it any easier to describe. The title itself is actually perfectly indicative of the feeling of the piece: a vortex is at work. This was the first piece of music I bought when I came back home after this trip, and while the recording by Ensemble Risognanze is outstanding, the flute is much more out front, which makes me appreciate, in retrospect, how balanced the performance by the Quasars Ensemble, led by Ivan Buffa, was. A stunning piece of music, adroitly presented. A little later in the evening, a string quartet from Rotterdam, the DoelenKwartet, played two sets of music. These pieces were so dense and so technically mastered that all the compositions tied me further and further into a taut, crystal knot. I remember nothing but the feeling of being torn apart and only peremptorily collaged back together.

For more inundation, the night was capped with a concert of solos. First up was guitarist Elliot Sharp, whose shtick seems to be more about the display he puts on than anything heartfelt or musically motivated. He taps the guitar (and whatever special bass strings he has installed on his custom instrument) with his fingers and hands. His set seemed like a catalogue of techniques found and incorporated, not discovered out of inner or sonic necessity. If I want to hear guitar pyrotechnics, I'd rather listen to Robert Fripp's League of Crafty Guitarists, or even Joe Satriani or Eddie van Halen, Steve Vai or Frank Zappa. The idea that lots of notes and lots of speed in playing those notes might equal rigor of thought is a complete misnomer, with Sharp as exhibit A. If you can do all this great virtuosic shit on guitar, why not put it to more interesting use? Sharp could in fact be the embodiment of empty, dated pretension, of pulling concepts out of the smoggy zeitgeisty air that sound important but mean nothing when so superficially applied to aesthetics: his bio said he had "pioneered ways of applying fractal geometry, chaos theory and genetic metaphors to musical composition and interaction." I hate to be so dismissive, but regardless of how much Sharp might mean that, anyone who studies those fields beyond a cursory perusal would roll their inner eyes at such concept-dropping, especially when the aesthetics that supposedly result from it are so shallow.

Ostrava celery root. I had to beg the grocery store police to let me keep this photo - they made me erase all the others I took inside the store.

To my immense pleasure, and now knowing anticipation, the violinist Hana Kotkova appeared again, this time performing Pierre Boulez' "Anthèmes 1" (1991/ 94), a piece for solo violin. Because I had been so astounded by her performance the night before, I was glad to have the opportunity to hear her in a solo context and see if my original impression of her playing stood up. Indeed, her playing was absolutely thrilling and soothing at the same time. The unique quality of her tone literally triggers some part of my brain that puts me under a spell, but a spell of concentration, enlightenment and pleasure. It reminded me of when I was seven or eight years old and would be babysat by one of my mom's coworkers, Lucille Clemens. She would sit me next to her and tell stories about when she was a child, playing on a farm. Yes, many artists hold dear and revere some notion of storytelling and its powers; I have no interest in stories. Instead, what impressed me about Lucille's storytelling time was simply the quality of her voice as she spoke. She could have been talking about car insurance - what mattered was how she spoke, and how it made me feel. Kotkova's music, regardless of what she's playing, has the same power to take control of me, transporting me into a liminal state between dreaminess and total awareness.

Robin Hayward's solo tuba piece "Release, Tone, Redial" starts with so much silence that I thought it was going to be another one of those edge-of-audibility, Michael Pisaro infatuation-enclave exercises. But then a note exploded out of all of his valve-breathing that was very well-timed and well-contoured. With newfound attention, I noticed that the play between his breathing sounds, the wet breath accumulated in the valves and the warbled/ bent note articulation that occasionally burst forth revealed a great understanding of rhythms in space. He created very interesting tone colors through his buildup of breath in the valve, like twisted CB radio static with harmonic interference.

From Texas Thunder Soul 1968-1974 liner notes by Eothen Alapatt

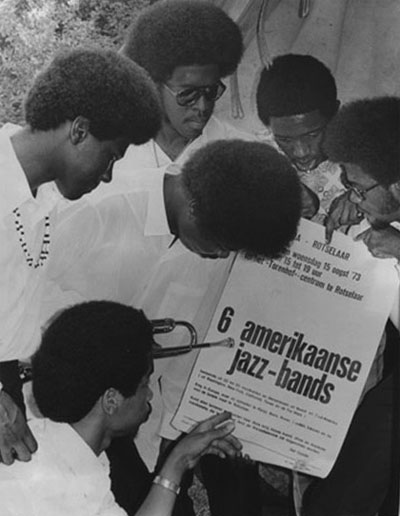

Members of the Kashmere Stage Band with promotional poster.

From the early 1960s through the mid 1980s, most every American high school band director took the initiative to record and release his pupils' music on vinyl. Capitalizing on custom record pressing plants in different areas of the country – Cardinal in the Northeast, Gabor Industries in Florida, Delta Custom in the Midwest, for examples – and Saugus, California-based Century Records' user-friendly recording/production process, band directors manufactured records to sell to students, parents and any other benign soul who could stomach their typically rough-hewn, amateurish cacophony. Countless thousands of high school band records have been recorded and released, most packaged in whatever stock sleeves the manufacturing plant had on hand, pressed in runs of a few hundred pieces and distributed – if you can call it that – within the limits of whatever town or city the school called home.

This is not to say that all high school band records are worthy only as nostalgia pieces for those involved in their production. Although a good bulk of the early '60s high school recordings feature symphonic bands, marching bands and the random glee club, by the late '60s, high school band directors often shaped their ensembles as "stage bands": performance bands styled in the form of the jazz big band. The big band era of America's jazz history (roughly speaking, the decade from 1935 through 1945) had long passed. But some leaders from the big band era – notably Duke Ellington and Count Basie – remained attractions though the '60s, and leaders such as Stan Kenton and Woody Herman kept relevant with a younger audience by embracing the changes occurring in popular rhythm within the '60s incarnations of their bands. Many high school stage bandleaders themselves were either products of the big bands or had grown up surrounded by the sounds of the swing decade. They pressed their young students to excel in a most rigorous musical form.

A stage band's members were often more interested in putting forth their take on popular rhythm than proving that they could swing like Bennie Goodman or Glenn Miller. They were kids, after all. Though their youthful energies were somewhat restrained by the big band form, this desire has led to large number of interesting (and a small number of amazing) recordings. By the late '60s, when the funk beat (alternatively labeled "rock" or "soul" beat) took over as the prevailing rhythm behind popular music, it wasn't uncommon to hear a white stage band attempt covers of tunes by horn-heavy rock bands such as Blood, Sweat & Tears and Chicago. It wasn't uncommon for a black stage band to cover funk king James Brown and his JBs (big) band. Occasionally, an enterprising band would come up with an original composition that melded the best of jazz, rock and funk. And the music they created wasn't only novelty. The very fact that the Detroit Sex Machines were high school students when they recorded four of the best funk sides ever begs the question: wonder what Detroit's Southeastern High School Stage Band sounded like?

In large cities, where many high school stage bands sprung up in proximity to one another, a logical phenomenon often occurred: one stage band, and usually one band leader, catalyzed the development, and sound, of a region. Stage bands were competition bands by nature, and a winning band's formula would often be adopted by its followers. Often, the reigning bandleader would release a large number of albums (sometimes recorded in a studio, but most times recorded live), which both served as fodder, and a source of envy, for his compatriots. One example is Oklahoma City, Oklahoma, where L. Jerome Hick's awesome output with Douglass High School's Stage Band set the bar for the region's bands.

But in Houston, Texas, Conrad O. Johnson pursued a far loftier goal with his stage band at Kashmere High School, a predominantly black school located in the city's north end (referred to in Houston as "Kashmere Gardens"). He wanted to lead not only the best high school stage band in Texas, but the best high school stage band in the world. Our opinion is that he succeeded, and we're thankful that he thoroughly documented his band's progress, so that we can present to you the Kashmere Stage Band's musical legacy.

In the mid '60s through the '70s, in Houston's bustling metropolis, Johnson (known by many as "Prof.") made a career of producing leagues of musicians capable of playing competitively with any band in the nation, professional or otherwise. More than simply a product of the big band era (his childhood friends and early musical peers included legends like Illinois Jacquet and Arnette Cobb), Johnson bestowed a living history to his young students. And while many band directors simply tolerated the use of popular rhythms in their stage bands, Johnson embraced the funk movement that enveloped his kids. He encouraged composition – both by writing original funk songs for his band to perform and by allowing the Kashmere Band to play songs written by band members. Never one to succumb to novelty, Johnson didn't simply throw funk beats beneath a jazz song to please his kids. He instructed his band to play funk because he respected the funk idiom in the same way he respected jazz. Nor did he simply borrow charts from progressive big banders such as Herman, as was common amongst high school bandleaders from the era. He arranged nearly every one of his band's songs himself, and those that he didn't arrange he allowed his students to arrange. He worked year-round with his eager charges, constantly pushing the limits as to what their band could accomplish. He built the Kashmere Stage Band from scratch and his winning combination of powerful funk rhythms beneath expertly executed jazz solos quickly influenced those bandleaders directly within his sphere and those he met – and almost always bested – in competitions across the world.

Kashmere Stage Band on NPR's All Things Considered

Excerpt from Stone Throw Records Interview by Egon

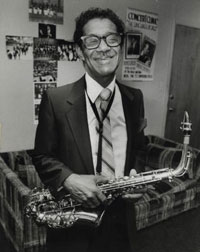

As the leader of the Kashmere Senior High School's stage band in Houston, Texas, throughout the 1960s and 1970s, Conrad O. Johnson produced leagues of musicians – guitarist Melvin Sparks included - capable of playing competitively with any band in the nation, professional or otherwise. A product of the big band era himself, and a childhood friend of legends like Illinois Jacquet and Arnette Cobb, Johnson bestowed a living history to his young students. And he had the foresight to embrace the funk movement that enveloped his charges. He recorded eight LPs and a handful of 45s with the Kashmere Stage Band, but laments, "The records are just a facsimile. Seeing and hearing that band perform was unexplainable."

"Kashmere," the band's trademark, left Johnson's pen when the bandleader was 53 years old. A contemporary-styled drum feature, Johnson's creation needed the talents of a powerful funk-driven drummer. Enter Craig Green, a skin-smashing prodigy who left his home district to join Kashmere's ranks in his senior year. A well disciplined young man, Green never hot-dogged the twelve drum breaks in his showcase piece. "Stay in the pocket, keep the groove steady," Green remembers. "Never let the tempo fluctuate, but keep the energy up."

Here, both Johnson, now nearly 90 years old, and Green, one of "Prof's" finest students, reflect on the powerhouse that was the Kashmere Stage Band.

E: You were born November 15th, 1915 in Victoria, Texas. This much I know.

C: That's right. I've lived in Texas my entire life. I moved from Victoria to San Antonio, and then when I was nine, I moved to Houston.

E: Tell me how you got into music.

C: I got into music when I was about 12 years old. I saw an article saying if you sell 12 cans of a salve, you'd get a saxophone.

E: A "salve?"

C: Yes, a salve. At that time they had salves that you would put on your skin – you wouldn't eat it – you'd put it on your skin. And it would heal you if you had a little problem. Anyway, that article interested me. I said, "I know I can sell 12 cans!" So I sent off and got my cans and sold them all in one day. But they sent me a toy saxophone! And I was sooooo disappointed. But after I got over my disappointment, I went on and started playing on it. I learned everything they had on the book that was included. And then I moved on. In two days, I knew that I was hooked and would become a musician.

E: So you're self-taught.

C: No. I'm partially self-taught, but I went to school for it. I went to Wiley College, Houston College, University of Southern California – I studied for it!

E: You started in Houston. What musicians were you looking up to?

C: In my younger years, I looked up to Jimmy Withersmith – a sax player, Duke Ellington, Count Basie. Basie was a latecomer on the scene, but I really did love him. There were many sidemen that I admired, like Lester Young.

E: The Big Band era.

C: That's right, I came up in the Big Band era. I played saxophone and clarinet.

E: Buddy Smith told me that you came up with Illinois Jacquet!

C: Yeah. We used to play. Arnette Cobb too. We all lived in Houston, I played…. well, during those days it was different. To advertise, if a company put out - let's say a new brand of soda water – well, they would advertise it by putting a band on a truck and letting the truck drive around the city. Or they would have us play at the stand where they were selling, and the music would draw people to the stand. Illinois was a drummer at that time! This was around 1939 or 1940.

E: Were there any other local musicians that blew your mind?

C: There was a band called The Birmingham Blues Blowers. This was in Houston. We listened to them quite a bit. They played many proms at the school. I remember peeping through the windows of the gymnasium when I was a little kid to watch them play. I said, "I want to do that!"

E: When did you realize that music was something you wouldn't be able to give up?

C: As time progressed, I got deeper and deeper into it. And I played in the school band at Jack Yates High School in Houston.

E: Your dad led that band, didn't he?

C: Yes, but my dad was actually a dentist! He had worked his way through college playing music. He wasn't a musical director per se; he was a trumpet and flute player. And he was a tremendous vocalist. I had him for about 3 years.

E: I bet you he whupped you into shape!

C: Well, one way or the other! (Laughs) Anyway, the band made a trip down to Dallas and that did the rest of the hooking. I knew then that I would always be involved in music.

E: When did you join your first professional band?

C: Just out of high school. I played almost every joint in Houston, whether they had small bands or whatever. I was all over the place.

E: What was it like, being a black performer at the time of Jim Crow? Segregation, outright racism?

C: I'm going to explain it to you like this. At that time, the people – black and white - who really had the money to hire the players wanted black performers. Because they were the naturals - blacks introduced jazz to the world.

E: So it wasn't hard for you to get gigs?

C: Man, we had almost all the gigs! I was working all I wanted to. Blacks introduced this music. If people wanted to get real jazz, they had to hire black bands.

Read the interview in its entirety at Stone Throw Records.

By Abigail Wilsher from The Portsmouth News, May 28, 2004

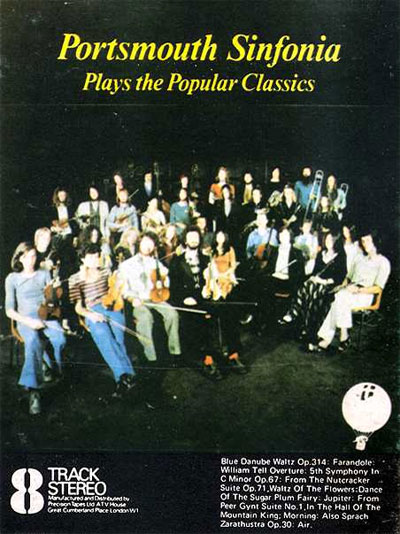

Portsmouth Sinfonia's Plays the Popular Classics 8 Track cover

Liverpool had The Beatles, Manchester had Oasis - and Portsmouth had a scruffy band of classical musicians who couldn't play in time or in tune. But that slight disadvantage - and the tag of the World's Worst Orchestra - didn't put the Portsmouth Sinfonia off. And now its members are remembering the day, exactly 30 years ago today, when they hit the big time and sold out a concert at London's prestigious Royal Albert Hall.

The Sinfonia was formed in 1970 by a group of students at the Portsmouth College of Art, who wanted to take classical music out of the hands of the 'tuxedo-Nazis' and return it to the people. Although many thought the less-than-competent ensemble was a joke, it was never intended to be a spoof. Everyone turned up to rehearsals and everyone put their heart and soul into the project. It's just that if some of them played a few wrong notes - live or on their recordings - it wasn't the end of the world.

Martin Lewis, long-time manager of the Sinfonia, got involved in 1973 while working for their record company, Transatlantic. He said: 'I just fell in love with them. They had something rare and beautiful. They were uninhibited by the stuffy rules and all the things I hated about classical music.'

The famous Albert Hall date came after the Sinfonia wrote to the BBC in 193 asking if it could perform in one of its promenade concerts, billed as making classical music accessible to the masses. But all they got back was a standard letter saying thanks, but no thanks. Mr Lewis remembered: 'I said: "Right, well then we'll just have to book the Royal Albert Hall - and we did".

The gig was the Sinfonia's finest hour. An aspiring pianist called Sally Binding performed Tchaikovsky's Piano Concerto number one written in the tricky key of B flat minor. The orchestra was having a few problems with the sharps and flats, so Miss Binding completely re-learned the piece in a more manageable key.

A 350-strong choir was recruited to sing the Hallelujah Chorus from Handel's Messiah and the Royal Albert Hall's canons were wheeled out for a dramatic rendition of Tchaikovsky's 1812 Overture.

Mr Lewis explained: 'I was 21 years-old at the time and when you're 21, you know everything and there's nothing you can't do. I might have a few more reservations if I was trying it now!' 'It was beyond exhilarating. The lunatics had well and truly taken over the asylum and it was great.'

The Portsmouth Sinfonia was founded by Portsmouth College of Art's music lecturer Gavin Bryars and students, including Robin Mortimore, James Lampard and conductor John Farley. It soon blossomed into an 82-strong band, including prolific members such as composer Michael Nyman, who went on to write dozens of well-known film scores, including the haunting music for The Piano. Also among the ranks was one Brian Eno on clarinet. He went on to produce albums for many well-known groups and artists, including David Bowie and U2 to name but two.

The Portsmouth Sinfonia played its last concert at the University of Paris in 1980, but its cult status around the world never waned. And now 30 years on, Manager Martin Lewis feels it's now high time there was a reunion. 'I think we should do the Albert Hall again,' he said. 'I mean, where else is there? The burning question is: will they still have what it doesn't take?'

Mr Lewis also masterminding a campaign to have the orchestra's albums, unavailable for 25 years, re-released on CD for a new generation of fans. Rare copies of the orchestra's masterpieces make the odd appearance on internet auction site eBay from time to time and can fetch anything from £60 to £100.

Their first recording, released in March 1974, was The Portsmouth Sinfonia Plays the Popular Classics. It was a melee of not-quite-spot-on renditions of popular and not so well-known pieces, including Bach's Air on a G String and Jupiter from Holst's the Planets Suit.

The second album, released in October 1974, was Hallelujah! - Portsmouth Sinfonia Live at the Albert Hall.

Around that time, the London Symphony Orchestra was churning out orchestral versions of well-known rock songs, such as Classic Rock and Classic Rock II.

Next came 20 Classic Rock Classics in the summer of 1979. The Who's Pete Townshend contacted the orchestra and said its version of Pinball Wizard on the album was second only to his band's own version.

When the Royal Philharmonic released its cheesy Hooked on Classics album, which featured medleys of popular greats, the Sinfonia retaliated with its own version, Classical Muddly, which made it into the top 30 and became a cult classic.

It would have made a bigger impact on the charts, but its release was delayed by a legal wrangle with the people who owned the copyright of Richard Strauss's Also Sprach Zarathustra. 'They said we had made alterations to the piece, but we said that it wasn't intentional, but happened more as a result of incompetence,' said manager Martin Lewis. 'You can't really argue with that

The Portsmouth Sinfonia at the Royal Albert Hall, 1975

Excerpt from the July 1981 issue of Keyboard Magazine

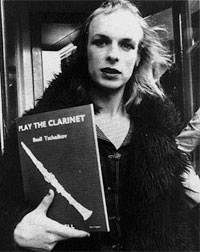

Another intriguing project that you were involved in a few years ago was the Portsmouth Sinfonia. Could you talk a little about that?

The Portsmouth Sinfonia was founded by an English composer named Gavin Bryars. He started it at Portsmouth College of Art, hence its name. The philosophy of the orchestra was that anybody could join. There was no basis of skill required for joining. The only condition was that if you joined you should attend rehearsals and take it seriously. It wasn't intended as a joke - though it was sometimes extremely funny. The orchestra only played the popular classics, and it played only the most popular parts of these popular classics, the bits that everyone knows: Da-da-da dum, da-da-da dum. At its biggest it was about 78 people strong and it had a complete complement of orchestral instruments. Most people when they talk about the Sinfonia talk about it as though everybody in the orchestra was incompetent. This wasn't true, exactly. There was a range of competence, from extremely competent - we had some bona fide virtuosi in there - to completely incompetent. What was interesting about it was this mix. It wouldn't have been more interesting if it had been all incompetent or all competent. It was this particular mix so that in any piece what you heard was a number of approximations of how the piece should be played. You'd hear the melody of whatever it was, hidden somewhere among all those approximations of the melody. It was like a very blurry version, a soft-focus version, of classical music, and it produced some beautiful music. I really liked some of those results. There were some exquisite moments - the mixture of chance and choice, you know? Anyway, the Sinfonia existed, let me see, from 1969 to about 1974 or '75. I joined in 1970, and I ceased to be active in 1974, mainly because I wasn't in England a lot of the time any more.

From that description, it sounds as though the Sinfonia might have had some impact on the way your records sound.

It certainly does. In some quite specific cases. There's a song on Another Green World called "Golden Hours." I wanted the Portsmouth Sinfonia effect on the voices. I wanted a lot of voices that were a little bit off with one another, so I overdubbed the voices myself but I didn't use headphones. The engineer would just give me a cue when to start singing. He was listening to the track in the control room, and when he cued me I would start singing, so that my pitch is deliberately slightly off and my timing is slightly off, to reproduce that effect. Also, on Taking Tiger Mountain I used the string section from the Portsmouth Sinfonia on one of those songs, a song called "Put A Straw Under Baby."

You've been quoted as saying that music played by untrained musicians can be as interesting as music by trained musicians. If an untrained musician wants to take advantage of this idea, can they just do it any old way, or is there a certain approach or philosophy that would be a good idea for them to keep in mind?

I should think there are quite a lot of things it would be a good idea for them to keep in mind [laughs]. Unfortunately, that position of mine has frequently been misinterpreted, and I've paid the price, I can tell you, by receiving hundreds and hundreds of tapes from people who say, "Hey, I'm an untrained musician. I've followed your advice, and I've decided to send this tape." And unfortunately most of the tapes are really not that interesting, you know? So I've paid for my theory there. But my position was developed from two points of view. First of all, folk music is often played by untrained musicians. Part of the beauty of that music is in the way that variety is achieved, not by people deliberately trying to do something different from one another, but by accidentally doing something different. For instance, if you listen to group folk singing you often hear strange and lovely harmonies that are actually inadvertent. They result from the fact that somebody can't sing on the register that the main voices are in, so they just find a pitch at some peculiar interval above or below and stay in parallel harmony from there onwards. So in folk music you often have this sense of a limitation being turned into a strength, which was really what I was talking about: Regard your limitations as secret strengths. Or as constraints that you can make use of.

To give another example of this, on the technological level, there are two approaches to going into the studio. Some producers go in, and they say, "Have you got the Lexicon 224 echo? Have you got this, have you got that? Oh, you haven't got that? I can't work here." Suddenly their world crumbles because you don't happen to have the new Eventide D949 phaser, or whatever it is, and they can't envisage working without this. But when I go into the studio, I look around and see what is there and I think "Okay, well, this is now my instrument. This is what I'm going to work with." Another example would be when you're faced with a guitar that only has five strings. [Ed. Note In fact the guitar Eno owns only has five strings.] You don't say, "Oh God, I can't play anything on this." You say, "I'll play something that only uses five strings, and I'll make a strength of that. That will become part of the skeleton of the composition." That's really what I mean, that any constraint is part of the skeleton that you build the composition on - including your own incompetence.

So, that's one aspect of the untrained musician thing. The other aspect is this I believe strongly that recording studios have created a different type of musician and a different way of making music. In some sense it's so different that it really should be called by a different name. The only similarity is that people listen to it, so it enters through the same sense, but in the way it's made it's really a different thing. When I make a record, very often I work rather like a painter. I put something on, and that looks nearly right, so I modify it a little bit. Then I put something else on top of that, and that requires that the first thing be changed a little bit, and so on. I'm always adding and subtracting. Now this is obviously a very different way of working from any traditional compositional manner; it's much more like a painting. So it's clearly a method that is also available to the non-musician. You don't have to have traditional technical competence to work that way. You can have it and work that way, but you don't have to. So I was trying to make the point that if you're working with electronic media in the recording studio, judgment becomes a very important issue and skill becomes a less important issue. If you're working with synthesizers in particular, some things are easier than others, but really you can do almost anything you want to. So what then becomes important is deciding which is the right thing to do. And that's the leap that very few synthesizer players make, I think. They generally just do everything they can.

So the weakness of the tapes you get from untrained musicians is that in addition to not having skill, they don't exercise their judgment either.

That's exactly right. They've gotten over the problem of not having skill, but they haven't moved into the zone of having judgment about what they do. I mean, people would probably be surprised to know my own rejection rate of my work. I must produce a hundred times the amount of music I release. The amount I release is a very small proportion. I reject a tremendous amount. And I don't feel bad about this. I don't think, "Oh, what a waste." The rest of it is sketches, in a sense, of what then comes out, so it's not wasted time, but it's not stuff I would regard as finished.

Do you keep the sketches, or do you erase them?

I erase some of them, but a lot of them I keep. One of the reasons I keep them is that my judgment is likely to change. In fact it's notoriously likely to do that. I'll sometimes pull out something that I did four years ago and suddenly I'll be surprised by an idea in it that I didn't actually notice at the time. Whenever you're working on something, you're working with some concept of what you're doing. You think, "Oh, now I'm being concerned with this, and this, and this." But later on you may suddenly realize that underneath that there was a secret concern that you weren't consciously dealing with, but which actually dominates the piece, and that concern might be the most interesting one. I do keep things on that basis. But sometimes I do things and I know they're just absolutely crap. There's no point in wasting storage space with those, so those go.

From Lost In Tyme

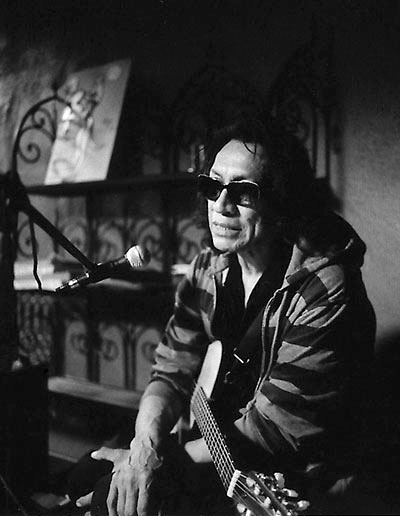

Sixto Rodriguez. Photo by Theo Jemison

Sixto Diaz Rodriguez is a US folk musician, born in Detroit, Michigan on the 10th of July 1942. He was named 'Sixto' because he was the sixth child in his family. However, he is also known as Jesus Rodriguez by South African fans. Rodriguez's parents were middle-class immigrants from Mexico, who left in the 1920s. In most of his songs he takes a political stance on the cruelties facing the inner-city poor.

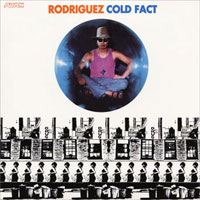

Rodriguez recorded some songs with a small recording company, who later folded due to financial problems. He did, however, manage to produce two albums - "Cold Fact", in 1970, and "Coming to Reality". They were relatively unknown in his home country, and most of the world, but unbeknownst to him went platinum in South Africa, where he achieved cult status. He was also popular in Zimbabwe, New Zealand and Australia. After the failure of the record company, he gave up his career as a musician. He was working on a Detroit building site in the late 1990's when his daughter discovered his fame thanks to a South African fan website.

Rodriguez is my father! I'm serious. He recently received an article from a journalist there who told him of the following. I went online to try to find out more info and was shocked to see he has his own site. Truly amazing. Do you really want to know about my father? Sometimes the fantasy is better left alive. It is as unbelievable to me as it is to you.

- Eva Rodriguez on the fan website's forum, September 12, 1997

"South Africa in the early 1970s was a very restrictive society," says Stephen Seger-man, a former Johannesburg jeweller who made it his mission to track down Rodriguez. "Cold Fact was never banned, but it never received any radio play, except on pirate stations like Swazi Radio, which weren't under the censor board. The song I Wonder had this line, 'I wonder how many times you had sex', which for South Africa in those days was about as controversial as it could get. For kids, it was like a joke song, they were like 'listen to this!'. Then they heard the album, and realised there was a lot more in it, it was trippy, it was beautiful, it had a lot of social content. It affected a lot of people in a lot of different ways. The commercial success was unbelievable. If you took a family from South Africa, a normal, middle-class family, and looked through their record collection, you'd find Abbey Road, Neil Young's Harvest and Cold Fact. It was a word-of-mouth success."

The word of mouth did not reach Detroit, where Rodriguez had given up his recording career after a second album, 1972's "Coming From Reality", vanished in much the same fashion as his debut. He tried an unsuccessful career in politics, studied for a BA in philosophy, worked in a petrol station and apparently "took part in Indian pow-wows throughout Michigan", before becoming a self-employed labourer. In South Africa, meanwhile, his record company seemed to have no idea of his whereabouts. In place of any concrete information, rumours spread. It was variously assumed he was dead from a heroin overdose, had been burned to death onstage, had been committed to a mental hospital, or was serving a prison sentence for murdering his lover: "Who or what Rodriguez is remains a mystery," claimed the sleeve notes to a reissued CD.

By Tristan Gulliford from Reality Sandwich, August 18, 2008

In The Alchemical Dream, a film produced by Sacred Mysteries and directed by Sheldon Rochlin, visionary author and counterculture luminary Terence McKenna relates some of the curious history of European alchemy, and the attempted creation of a religious utopia based on alchemical principles. Dressed as the famed Hermetic magician John Dee, McKenna strolls wistfully through the crumbling ruins and sweeping castle vistas of Eastern Europe discussing the lost secrets of alchemy. He gives us a tour of the last remaining alchemical laboratory in Heidelberg, and tells a fascinating story of political intrigue and bohemian experimentation in the 16th century.

The alchemists were after what McKenna describes as a "magical theory of nature." They used precise and calculated methods that would pave the way for the future intellectual development of some important sciences such as chemistry, biology, phenomenology, and psychology. Their intention was to transform the human spirit and the physical body itself into something divine and wholly other, something resembling the odd and spectacular alchemical art of the time. They experimented with myriad combinations of special chemicals, magical formulas, and complex distillation processes designed to produce the fabled "philosopher's stone": a metaphorical goal which can be read in many ways. In essence, the alchemists were trying to bring heaven down to earth by merging spiritual mysticism with the physiological exploration of alchemical mixtures.

According to McKenna, the group of European alchemists who centered around John Dee and the British court of Queen Elizabeth I in the late 1500's believed that the spiritual philosophy of alchemy was so profound and full of potential that it should be embraced as the popular religious paradigm of the day. The Christian preacher Martin Luther had started a Protestant reformation in 1517 with the 95 Theses and now, a century later, Dee felt that the world was ready for an alchemical reformation. With this idea of a religious reformation in mind, Dee and a group of court alchemists traveled to the palace of King Frederick V of Bohemia in 1618 with the intention of establishing a new alchemical kingdom.

This alchemical dream lasted for about a year before the Austrian dynasty of the Hapsburg family got wind of the reformation plan and disapproved of Frederick's kingship, quickly dispatching an army to lay siege to the kingdom of Bohemia and Frederick's court. After a brief period of fighting Frederick was defeated at the Battle of the White Mountain on November 8th, 1620, and the Bohemian hopes of establishing an alchemical religious state were destroyed. While the bulk of alchemical knowledge was lost to Western civilization after this time, the intellectual threads of this esoteric philosophy can still be found in the modern world.

As McKenna points out, this attempted reformation was not entirely dissimilar to what happened in the social climate of America in the 1960's with the re-introduction of sacred plants into Western culture and the social upheaval that occurred simultaneously. McKenna describes the drug revival of the 60's as a sort of "failed alchemy" whose ideal was to transform the human spirit, but wound up as a splintered and marginalized movement, similar to alchemy. However, although alchemy was lost to Western civilization for a few centuries, some of the basic ideas can still be found scattered here and there in some esoteric religious practices, mystical writings, transpersonal psychology and art history books: themes of creativity, diversity, synchronicity, unions of opposites, and personal psycho-spiritual exploration which were all an essential part of the alchemical endeavor.

So while the dream of European alchemy may have apparently died in the 16th century, the underlying motivation of the alchemists – a desire for innovative and genuine spiritual experience – is a fundamental human characteristic that can be traced through many different cultures and time periods. As an example of this, at the end of The Alchemical Dream, McKenna makes an interesting historical footnote about a young solider named Rene Descartes who was part of the invading Hapsburg army which defeated the Bohemian kingdom. Shortly after this time, Descartes was visited in a dream by an angelic apparition who instructed him with a piece of advice which would fundamentally alter our world. The angel said to him, "The conquest of nature is to be achieved through measures and numbers." Descartes would go on to become one of the most influential scientists and philosophers of his day. For McKenna, this is a perfect example of how the spirit of alchemy (the spirit of inner human creativity) will continuously reappear at opportune moments and direct the course of human events in mysterious ways which we can only begin to understand.

Tristan Gulliford is a writer, dreamer, and aspiring myth-keeper who makes electronic music under the name "Dreamcode". He is currently attending the University of Colorado at Boulder.

To play, allow the video to load a bit then move the scrubber.