Facsimile Magazine, Published by Haoyan of America. Volume Four, Number Eight, 2010. ISSN 1937-2116.

Facsimile August 2010

Facsimile Magazine, Published by Haoyan of America. Volume Four, Number Eight, 2010. ISSN 1937-2116.

Welcome to the August, 2010 edition of Facsimile. When you ask yourself, "Who brings a horse to a funeral, not to ride but to mourn?", you can safely keep thinking of Vanity Fair. It is quite an honor to have been given the opportunity to guest-edit this fine publication. Fate can be brutal, but, to quote Larry Finer from the July 13, 2010 issue of Time: "The recession has dramatically reshaped women's child-bearing desires", so, whooh.

I've gathered here, for you, several fine pieces of fiction from the aeshetics behind the good minds of Wappler, Tudor and Stradal. Pursue accordingly. A one square cm spider is still enough to have a distracting girth when it scampers across your dashboard while driving. Three new video pieces are here-now unveiled by Peter Darchuk, Sara Ludy and Austin Meredith, the latter featuring the sculpture of Ms. Becklin, The Do Right Lady. She also has a show coming up in August, uh-huh, yes, information within. The spider's on the inside. The spirit of Arch Stanton all over it.

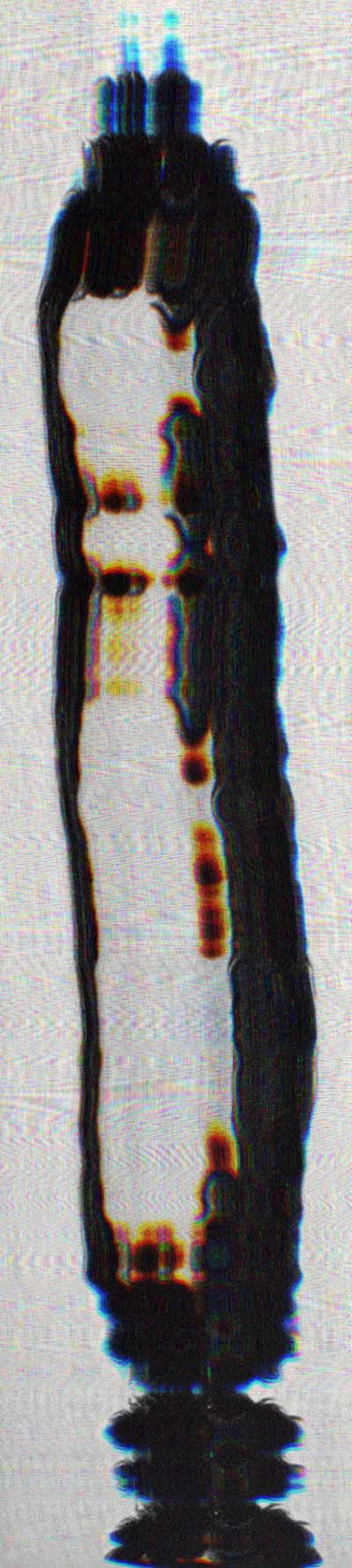

An essay by Labrat Driscoll examines the updated age-old question of personal suffering undergone for the sake of journalistic excellence (the Whole Earth Catalog vs. iPhone marketing), and Minsker has emerged on the other side a worn but better man. Which brings to mind the confronted video-poems of Dimitri Mittens. His words abut the videos like assymetric circles.

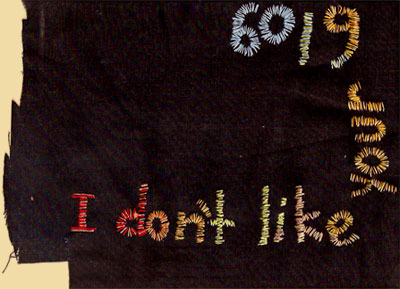

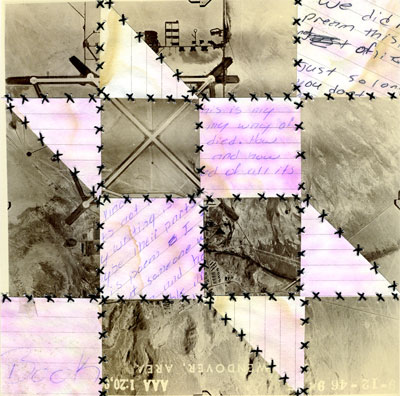

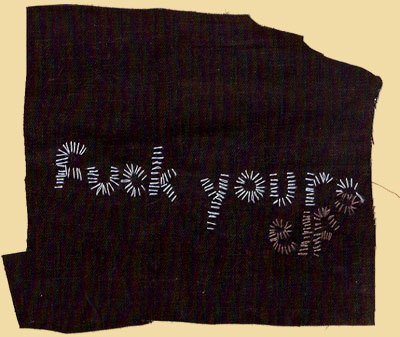

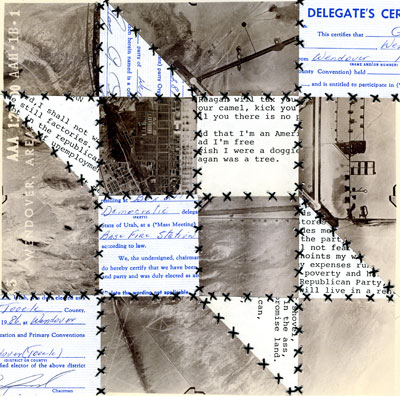

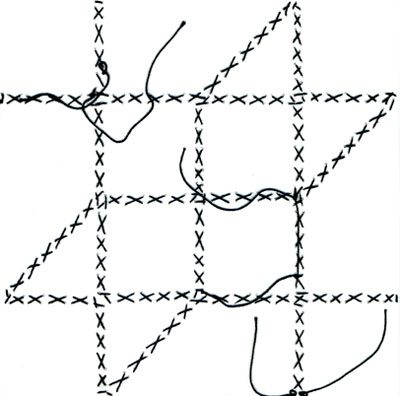

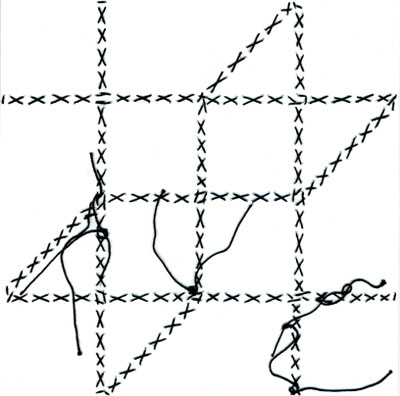

Sharing that cartographically unknown territory are some sewn map-texts by Jen Hofer, flipside and all: "Three Roads to California: Hand-Sewn Poems Made of Foraged and Donated Materials from Wendover, Utah". Go somewhere. I lost a 167 gram red Star Wraith on hole 17 at East Roswell Park last week, but get this: the guy who found it is a disc golfer AND a rock climber.

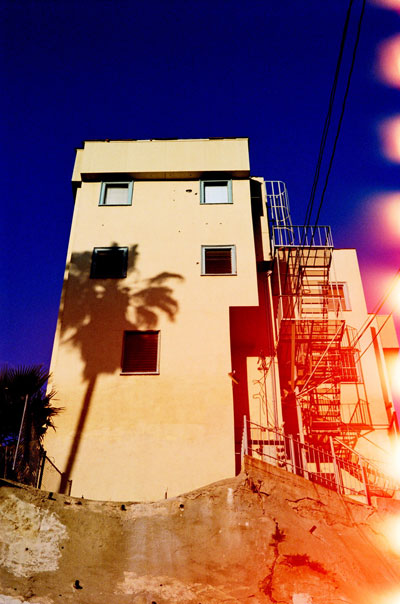

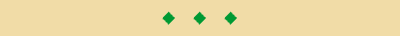

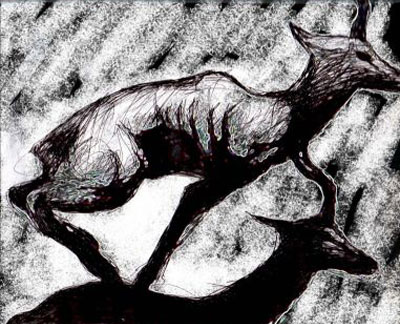

Visual art of the still variety, here it is, finally. And it makes me feel like I haven't seen anything worthwhile frozen in a long time, photos by Overcash, J. Allison and Sylvain D'Hautcourt to thank. Speaking of J. Allison, the bodies of work sampled herein make me want to wear my clothes and the clothes of others differently from here on out. Not inside out, but with a more louche, folded hang.

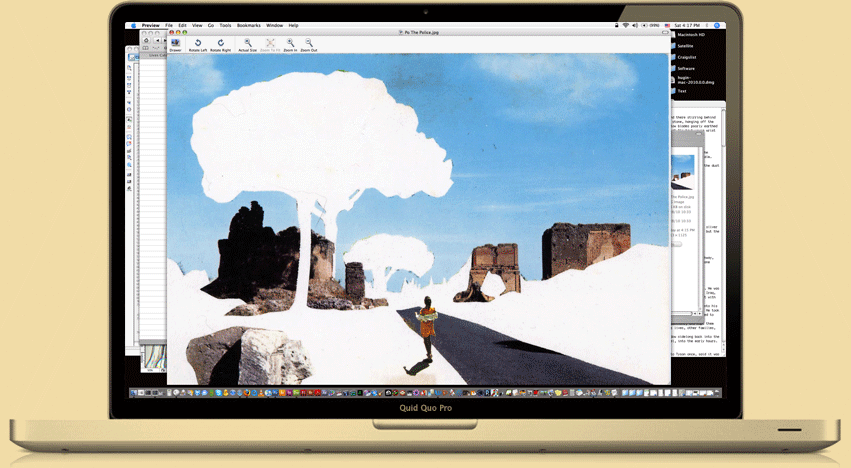

The images by Mr. Monk, on the other sweat droplet, form a birdcaged bridge to a world where technology is actually an advantage. It's about time. Which brings us to music, sweet music. While many of the contributors to this issue are working outside even their own 'regular' mediums, it is perhaps poet Will Alexander's piano piece that will give the loins of the rising sun something to sweat over. Solos by Champagne and John Rambo - on trumpet and etc. respectively - round off the trio of requested sonic offerings.

I've also supplied some extra videos from the world of dance (Jozef Nadj, Anne Terese De Keersmaeker) because... that's right. All other seasonings within should simply be tasted.

An ad for condos being built at Emory Point states: "You Have Reached Your Destination NEAR CULTURE" (their font change/ emphasis). While that may be EXACTLY what people want - to be near culture, not part of it, not inside it, not involved in it - you have been warned. Vicariously living off cultural fumes unavailable.

- Andrew Choate, August 2010

By Margaret Wappler

Mostly hot, right in the back of the eyeball, where the visual scroll gets projected upside down against a mirror of green. This one is a hard lurker that bullets in the stomach first. It represents what you thought you knew becoming what you didn't know until it breaks open everything you want to know but will never have the drugs to properly sort out.

The rescue of children, puppies, paramilitary op specialists, runaway despots, cripplingly hateful mothers, your own ugly wounded peppery shithouse attitude when confronted with challenge, fear, sadness, miscellaneous aches and pains, vertigo. Reserved for people who do things in elevators to impress strangers, like sing loudly or forge witty banter.

If I draw a point the size of a prick – your choice what kind - on your wrist and then it blossoms over your entire arm, and deadens out the capillaries and arteries but grows a couple new sets of veins for transferring worry, warmth, bankruptcy, night terrors, beautiful confused babies, stifled bedtime laughter, viscous offerings of questionable disease potency and starved planets of ambition, is that so bad?

In the spine, a rabid tingle, a scarlet fire up every notch till it swoops over the top of your skull and blesses your entire head like a celestial cap, warm and dominant. New grass guarantees a certain never-can-tell feeling about time. The first instant we all felt exuberance was in childhood, staring in the mirror, pulling down an eyelid like a scene from the California suburban wastoid version of Un Chien Andalou. The nearly violet eyeball registered a dull existential click – here you are! Have you been listening to this roar all along?

By Dwight Tudor

The interrupted silence of a palm orchard at night, whereby disquieted chirps could be heard here and there stirring behind the sound of boots, their soles not used for stepping but instead skidding helplessly over dirt and stone, hanging off the edge of a makeshift stretcher, their heels splayed and occasionally kicking like two recalcitrant plow blades poorly earthed and dragged backwards. The arm of an old man reached tired and long over a bony shoulder and tugged at the taut young wrist pulling him.

- Stop. This is it.

- Here?

- Goddamit child, stop. This is it. I didn't drag my father a foot further.

The young man bent his knees and set the handles of worn plank gently in the dirt. The old man turned to sit up and the stretcher buckled under the weight of his elbows. He watched the boy pick absently at a splinter in the heel of his palm.

- How d'you know?

The old man cocked his head as if the night might require some show of reverence, then thought better of it and spit the dust from his lips. When he spoke again he was surprised to find himself in near whisper.

- How? You take a good look at that palm there son, and burn it in your head...

The boy followed his gesture to the weathered tree. It rose above them with its dark fronds tethered to the crown and cascading down from the shadowy nimbus in long strips butchered by the wind.

- You'll know it, mark my words, when your time comes.

A moment of silence stood between them.

- Alright then. I guess I'll be taking your boots.

The old man looked down at the boy's bare feet.

- Indeed you will, it's a long way back.

- I reckon I can make it.

- I reckon you might as well try.

The old man passed him the boots and laid back into the stretcher.

- You'll see son, just yourself and strangers from here. Don't settle too far in that body, it's not yours to keep.

The boy took the boots by the laces and slung them over his shoulder. He looked out upon the morning night, now a dim sliver of opaque rose that lowered flat and beholden beneath the empty void of planets and stars. He turned to say something but the old man was already gone.

Tyson Daniels woke from his dream to the unseemly poke of a bottle prodding him in the ribs.

- Hiya boyo, wakey wakey.

He was cramped in the passenger seat of a pickup, the seat belt blistering sweat against his shoulder. The driver, a delinquent and inveterate liar named Jack, was veering the truck wildly along a poorly pitched corner of mountain highway, steering with the fingerless stump of one hand while the fully intact other proffered a near empty fifth of whiskey, one scarred knuckle of thumb standing between them and heaven.

Tyson took the bottle and held it up to the sun.

- That's it boyo.

- Where are we?

- Weaverville county, welcome home.

Tyson gently swished the bottle around and watched the light brown liquid sway against their momentum. He took a swig. He was wary of the fact that Jack knew anything about him, crazy dumb bastard. He claimed to have lost his hand to a bomb in Iraq, but anyone with eyes in their head could tell by the clean cleave of scar that it was much more likely he'd passed out with his hand lying on a railroad track. Jack used to boast that if he could diffuse a bomb, he could play the piano.

Tyson held the bottle up again and watched the humid sun sparkle bronze through the bourbon. He sunk languidly back into his seat. When his old man had passed Tyson decided to skip the funeral but stopped in to take a last sweep of his house. He took two things. One was an old portable film projector. It had the faded brownish finish of a copper penny. His father used to set it up late at night. He had this collection of other people's home movies, little film reels that looked like toy versions of the ones you see in theatres. He'd pick them up randomly here and there at yard sales, auctions, and kept them locked up in his liquor cabinet. When he got drunk, he'd sit up alone and watch them, other people's lives, other families, their birthdays and vacations. Tyson had a room off to the side of the house and he could see out his window sidelong back into the living room so that sometimes he'd sneak up late at night and watch his father drink, reel after reel, into the early hours. It was just about the only regular thing they ever did together.

The second thing he took was a pistol that the old man had inherited from his father. He showed it to Tyson once, said it was a German officer issue from the Second World War, collectors item. It didn't work, the action long since locked up, but Tyson took it. The only real girlfriend he'd ever had once told him, upon hearing this story, that she loved him. She was great, and he probably loved her too, but they grew up differently and somehow let that become an issue. But she'd been really into movies and used to call him after some French actor she liked. She had one of his movie posters hanging in her bedroom. Tyson allowed there might be a slight resemblance but she claimed it was because of his life and who he pretended to be. He never really understood what she meant, but at the bottom of the poster was this great quote, "All you need to make a movie is a girl and a gun". He loved that. She was the girl and he'd be the gun. He'd always wanted a tattoo that somehow expressed that, even long after they broke up, and when he got out of juvenile detention the first thing he did was go to a tattoo parlor and tell the ink man about the quote, but the man just laughed at him and said if he really wanted it he'd put that on his arm but it was just about the dumbest thing he'd ever heard. He definitely loved that girl, thinking about it now.

They skirted another steep shoulder and Tyson steadied himself with his hand on the dash. His arm was sunburnt from days of hanging it out the window. He passed the fifth back to Jack, who hollered something lost in the wind. Tyson settled back against the seat and closed his eyes and when Jack started talking again, he remembered something that girl had once read to him: Who could ever be forgiven for interrupting a dreamer?

A boy pushed a deflated soccer ball across a yellowing and dusty lawn. His lanky frame was held aloft by two adolescent legs dressed in cut-off khakis, and when he planted his leg to kick, his knees stuck out from the frayed edges like awkward knobby things that threatened to snap and collapse.

His playground was the front yard of a single story millhouse, one of a dozen or so stretching down the dead end, all of them tied together by a thread of jaundice that spread across their lawns in a thinning quilt, one that had been ripped down the middle by a swollen and cracked gulf of asphalt. A sign at the end called it Devereaux Street.

The boy flicked the ball up and kicked it through a hedge of azalea failing in the late summer sun. He stumbled after it and struck it again, falling to the dirt. He raised his head as the ball swerved into the street and just missed the tire of a white pickup speeding by. An airbrushed effigy of a bald eagle stared back at him from the tailgate, its talons outstretched as if it might just lunge unpainted and swoop his flailing soccer ball.

- Joseph, what did I tell you? You watch that traffic, I swear. Like talking to the… And how, in one and right straight through the other... I tell you...

Joseph nodded his head without getting up or even turning to acknowledge his mother standing on the porch, an infant swaddled in one arm and a phone tucked up against her shoulder. She turned and went back in, letting the front door slam behind her.

Joseph rolled over in the dust and snuck behind the azalea, taking cover with a bed of crunching dead flowers. The pickup pulled to the curb several houses down and sat there, idle in the July sun. Tyson Daniels emerged from the passenger side and stepped onto the lawn. He took a long look around, and then kicked at the ground, scuffling the reddish-brown dust up around his boot. Joseph rustled under the shrub and Tyson turned to find him. They stared at each other for a moment before Joseph stood up and brushed the dirt from his khakis. Tyson watched him, then waved. He tried to force a smile but Joseph just stood there and stared. Tyson lowered his hand. Jack jumped from the cab laughing at something and nearly fell flat. The empty bottle of whiskey tumbled with him and smashed on the asphalt.

- Hey man, there's that fucking retarded kid. Hey kid, did you miss us? What's for dinner? Why'dnt you have your mother come on down here and make us something to eat, tell her to wear something skimpy, like one of them...

- Shut up Jack.

- Why? That damn woman's nothing more than a damn whore.

- Shut up. He's a kid.

- He's a retard. And that mother of his aint fit...

- Stop. C'mon, he can hear you.

- Fine. It's your world, brother, I'm just living in it.

Tyson tightened his face and tried again to force a grin but Joseph just continued to stare with a hollow and blank expression. He watched as the two men walked up the steps and entered their house, then turned to his ball sitting in the gutter, its worn backside upturned to reveal a threadbare underneath of gauze.

He walked over and collected it and punted it into his yard, then set off back past his own house and into the woods behind, following the line of a small trail worn into the underbrush. He followed it deep into the woods, well beyond sight of any house and came to stop at a large granite stone sitting exposed from the dank soil. Dried moss covered the top of it in a crust that fell off to the touch and left mangy patches where flecks of silver mica swarmed with tiny red insects glowing in the dappled sunlight. Joseph sat on his heels and watched them until a breeze swept through the pine needles and sent a chill across his skin. He got up to pee and then rounded the stone. On the far side, facing away from the trail, was a hidden nook dug from the soil at the base of the rock. It held a longish bundle wrapped in newspaper. Joseph knew it because he'd placed it there the day before. It was covered now in flies, and he swatted them away and gathered the package with careful hands. The contents were limp and malodorous, lop-sided and rotting, but he gathered it gingerly and tightened the newspaper around it. The nook left empty took the appearance of a small empty grave.

Joseph tucked the package carefully under his arm and set off again, this time diverting from the trail and following a less obvious line that meandered through a fern grove and then rose up and over a section of squat pine that became first thick and then attenuated to open on a small clearing that sunk away from the forest. The field was about a half-acre square and sat flat with a dilapidated battery house covered in kudzu rotting off on the far end. The ground looked as though it had once been tilled but was now mostly overgrown. Joseph strode through the brown grass until he came to the edge of a patch in the center of the field. Here the brush had been meticulously cleared in the measured shape of a circle, about sixty feet in diameter, and starting at the center and radiating outward in all directions was an intricate and symmetric arrangement of metal debris. All manner of imaginable scrap and rusting junk: bicycle parts, small discarded pieces of farm machinery, corrugated gutter, corroded tools, some of it so rusted that it was hard to tell what it was. But all of it strictly placed, according to size, color and shape, in a fastidious pattern of tight circular design.

Joseph stood at the circumference and studied it with a critical expression that evinced neither pride nor awe. He walked along the perimeter, the newspaper cradled in one arm, inspecting his work, occasionally stopping to perfect the position of a loose piece here or there with his foot, until he reached the battery house which stood like an oblong and disheveled keystone on the far side of the clearing.

He stood for a moment, solemn as the afternoon sun, then reached down and stretched the neck of his t-shirt, tucking it up around his nose. He folded the bundled lump of newspaper with both hands and pushed the creaking wooden door with his shoulder. It was dark within, the only light trickling in through windows covered with generations of weed and wrapped inside by tightly woven and rusting cage. He crossed the threshold and flies swarmed to greet him, buzzing with a rage.

Joseph sidled into the kitchen back home and watched his mother feed his little brother from a bottle of formula the way she always did in the presence of company. Diluted milky liquid trickled down his chin and she caught it in a crisp new bib decorated with the image of a child kneeling to pray in cartoonish cross-stitch.

Judging from the look of satisfaction on her face, the bib was a gift from Ms. Tobin, sitting on the other side of the table. Joseph noticed the way she graciously pretended to ignore the trash bag at the wall by her side, preferring instead to study the polished patina of her loafer as she swept it back and forth across the buckling linoleum. She raised her head when he entered and watched him quietly round the table and stop by the sink.

- Well, Mrs. Yancey says her husband Nate, you 'member Betty and Nate? Well, he said it aint no fox likely to try a dog that size. That cat and them chickens was one thing, but a big ol dog like that, uh-uh, no way.

- Well then where does he think it got to? What with that blood you said?

- I know… I declare, I don't want to think about it. But I aint lettin Tamara out no more without me. I don't know what I'd do. Did you know Betty and Nate used to live out in California? She said they had those coyotes, used to come right up in the yard and stare at you, like no man's business.

Joseph leaned over the basin of dirty dishes and turned on the water to wash.

- Joseph, there you are. How many times do I… are you gonna take this trash out before we bury ourself?

- …

- You… Mind your manners young man. Make a face like that in company.

- Oh come now, Caroline, don't be so hard. Joseph, why don't you come and see me next week? We've got vacation bible school all week long.

Ms Tobin looked at him with her dark brown eyes opened wide like two dilated craters. He turned off the water and his mother made a face to imitate him.

- Oh no Ms. Tobin, I don't need bible school, all I need is to kick my deadbeat dads old ball up and down the street all day. Hauling that old junk up and down who knows where. God knows… I swear, what am I gonna do with you? Don't you see somebody's talking to you young man? I have half a mind to take you…

Joseph swiped the trash by the top of the bag and dragged the plastic can banging around after him.

- Joseph? Joseph.

Outside the sky had amassed in twilight and the shadows fell down into the darkened woods behind his house, the depth defined by fireflies.

He heaved the plastic bin onto the dented rim of the large metal can and leaned back to offset his frail weight against the trash spilling in. The lid toppled back into place and let the light from the kitchen spill down on the surrounding grass. A glistening red fleck caught his attention. He followed a trail of bejeweled spatterings to the tall grass at the base of the house, where an eviscerated mass of feathers shivered in a small clump behind two little black beads. The tiny head shifted rapidly back and forth, swinging a beak that dangled on a cord of coagulating gristle. Two gashes, no thicker than a nickel, ran down its breast. Joseph stepped back to the trash and rummaged until he found a clean sheet of newspaper.

His father had once taught him that all you had to do to catch a bird was sneak up and pour salt on its tail. While it stopped to lick the salt, you could grab it. His father had told him this and laughed.

Joseph turned and surveyed the yard. The near night was quiet, nothing moved. The sky had turned a fiery red over the line of trees. The shadows too were silent.

Red at night, sailors delight. Red in the morning, sailors take warning.

Tyson and Jack set off at the crack of dawn. It had rained sometime in the night and the tires spit a fine mist off the road onto a grey web of rhododendron creeping up the precarious shoulder. Tyson was about to fall asleep when he felt the pickup swerve and accelerate. Jack sped past a logging truck. It responded with belated and coughing airbrakes and the sound rolled over the steep blue mountain like a snoring giant. Neither of them spoke, but it was clear that Jack was hungover.

Jack lit a cigarette and rolled down his window. Tyson pulled the old mans gun from his waist belt and held it in his hand, weighing it. His thinning hair slapped an ash around in the wind. He remembered the night once when his father had caught him up late watching him through the window. He was drunk and dragged Tyson petrified into the living room. He said he wanted to show him something, something he needed to see. Tyson just stood there, too scared to move, and the old man pulled a cloth out from behind the stack of movie reels in his liquor cabinet. He slowly unfolded it to reveal a pile of teeth, human teeth, clean as the day they were born. The old man looked at him, and said-These bodies of ours, they're not for us to keep, I want you to remember that.

Tyson slung the gun into the glove compartment and turned to the window. The morning sun was coming up through a grove of drenched and glistening hemlock. It flickered between the trees and he closed his eyes to feel the heat stipple forgetful across his lids. The smell of wet bark and ionized air, the cigarette smoke, it all strobed and mixed into a musky scent that reminded him of a childhood he preferred to remember. But then the pickup veered violently and gravity shifted beneath him.

He opened his eyes to watch Jack's face go blank and white. A semi swerved across the road in front of them and cargo buckles flew from its bed. A thick piece of unwieldy sheet metal flew off and seemed to float in the air for an interminable second before the wind grabbed it and sent it screeching in through the windshield. Joseph sat on his hands on the edge of his bed and felt the lump of his fingers slowly going numb beneath his thigh. His feet dangled just above the floor and every now and then he swung them in rhythm to the wailing crescendo of his brother screeching down the hall. He waited for his mother to get off the phone, and once convinced she was preoccupied trying to pacify his brother, he hopped off the bed and knelt down beneath the box springs.

The space under his bed was stuffed with plastic bins, old clothes and such, but he swept them aside. He pulled out a small wooden cigar box and set it at his thigh, then grabbed a random bin and set it open beside to provide some excuse should his mother interrupt him. He listened for her, then spread himself squat.

The top of the cigar box was a fading palimpsest of stamps and seals and little Spanish emblems. Inside it was a small folded cloth stained with chalky yellow clots. He pulled it out and set it between his knees, carefully unfolding it square within his lap. It was folded over multiple times, and the center flap stuck to the mass wrapped in the middle like a suppurating bandage. He peeled it back slowly to reveal a pile of little pills, their yolk-colored coats in varied stages of dissolution. He reached into the breast pocket of his pajamas and pulled out two more pills, glistening and covered with lint, and placed them amongst the others, then returned the cloth to the box and pushed it back under the bed.

His mother was in the kitchen and he could hear her talking on the phone again, his brother now quieted. He lifted the sheet and reached back under the bed, carefully obscuring the cigar box with another bin that moved easily in his fingers because long since emptied. A piece of labeling tape affixed to it read 'family photos'.

- Joseph? What are you doing? We're gonna be late for the doctor. Stop fooling, c'mon now.

Tyson felt his chest expand when he impacted the ground.

He went immediately out.

When he came back, it was cloudy, or overcast. The sky was hued with a pale shade of bluish gray. He felt his mind slipping through an erratic permutation of memories, each of them rising up disjointed and confused in welcoming tangents that seemed certain to distract him from what he was sure must be his body trying to die. He fought against them, a tempest of uncaged memories, and surfaced for a moment.

The sky was in fact blue. A plume of smoke spiraled up and pointed straight to it. He turned his head and the periphery of his vision began to flicker in concert with a tickling numbness that spread from his chest out through each appendage. He fought again, and slowly it dissipated into place with a light palpitating nausea.

He could see the pickup sitting surreal off the shoulder, as though it had casually pulled off the road for a picnic, a gigantic sheet of rusted metal poking out the front of it like a piece of burnt toast. He tried to sit up but the numbness resurfaced and he relented. The gun was lying on the pavement just a few feet from his face in a sea of sparkling glass, an image in abyss.

He lifted his head again and this time his body complied. He rolled onto his side and tried to rise on his arm, only to be greeted by a sensation of searing heat. He looked down his left side: The arm was intact but the skin from shoulder to hand was red and raw and studded in hundreds of tiny pieces of glass that stuck from the skin so that his arm looked like the curved gum of a shark, row upon overlapping row of sharp chips of teeth, each of them tingling in a burning socket.

He had to get up. He could smell gasoline and imagined the sound of a siren in the distance. He rolled to his right shoulder, pressed against the pavement with all of his strength, and sat up. His body was clumsy but it worked. He coughed and blood came up in a salivating mist. He stood up and vomited again, and then stumbled on his legs for a second before recovering enough to finally look around.

The smoke was coming from the cab of the semi, jack-knifed across the road. He could smell gasoline but didn't see any fire, just smoke. He turned back to the pickup but then thought better of it. He vomited again, harder this time, and spit a glutinous red bile. The shock of it cleared his head and he realized that he did hear a siren.

The mangled mass of the semi abutted against the upper shoulder of the mountain, the bed torqued and slung over the opposing shoulder to block the road. The siren reverberated over the hills as if approaching from no particular direction. He wondered how long he'd been out.

He bent down to pick up the gun and the smell of gasoline filled his head. He was covered in gasoline, it was everywhere. Overwhelmed and dizzy, he hobbled across to the lower shoulder. He crawled across the guardrail and was about to descend the embankment below when a loud hiss spit from the direction of the semi. He turned around one last time as the cab erupted with a whistling thump that bent the air around him. The sound, he thought, stumbling headlong down the embankment toward the ridge and the valley below, of a small animal sucked into a vacuum.

Joseph's mother sat gaunt and prim with her legs crossed stiff beneath an artificial palm tree in the waiting area of First Baptist Medical. His infant brother was silent in the car seat next to her. A flaxen plastic frond limped over the both of them.

Joseph sat on the couch across from them, pulling a bit of stuffing from a hole in the cushion. He pulled it out slowly, then coaxed it back in, again and again, his fingernails capped with little black crescents. His mother kept eyeing his fingers with a nervous tension, but she said nothing. She uncrossed her legs and Joseph watched as she noticed a hole in the knee of her panty hose. She leaned over and pretended to scratch at her calf so as to get a better look at it. A distorted silhouette of her head reflected back from the waxen floor and Joseph stared at the ragged contour of her reflection. The longer he looked at the floor, the more he began to discern a pattern in the pale green linoleum. It was covered in scuffs and streaks, little skipping striations, the residue of soles and heels and black plastic wheels and rubber crutch stops. Some disappeared neatly down the long desperate hall and into the bowels of the building, but others meandered restlessly between the magazine rack and the vending machine, hesitating beneath the TV, pacing back and forth from the nurses station to the waiting area, a gigantic swirling portrait of the forlorn patients and ignored loved ones who waited as their desperation was reduced to a world of vortices. The slender fluorescent tubes overhead also reflected back from beneath, completing the spectral pattern in elongated and luminous tombstones.

- Joseph, why… look at me young man, why are you crying? Pull yourself together. C'mon.

It was late in the day when Tyson finally stopped and turned to look back. He was in the valley now, and though his eyes naturally followed the steep green line of the ridge he'd just descended, there was really no reason, he could see clearly the site above: The wreck itself was obscured by the ridge, but a rolling funnel of pillowing smoke rose over it. The smoke dispersed in the lee of the mountain above, and trailed across the lower altimus in a long grey arc of flickering orange that looked to cradle the hidden conflagration in a taut but wispy arm. In the intermittent wane he could see a weak beating of red and blue, overlapping lights that danced across the slopes on either side of the smoke.

He sat in a small patch of fern, the shadows of their tattered fronds already growing long and crepuscular, and looked back at the mountain floating in its ashen nimbus, his eyes glassy and dilated. It occurred odd that the fire was still burning, but reason came to him in scuttled dispensations. He recalled crossing a stream earlier, somewhere near the base of the ridge, but did he follow it back up to a spring, or was that the memory of his grandfather pulling an old mason jar from a branch and forcing him to wash. Had that happened, had that old man come and grabbed him shaking in the night, as he lay supine with a girl, had there been a girl, on the side of a stream somewhere, some when ago. The old man handed him the mason jar and he clearly remembered drinking from it, mica shining in the silt at the bottom of it and flickering in the sunlight like the fireflies that surrounded him now, throbbing, with the mosquitoes stinging at the rivulets of sweat that meandered through the dust-caked glass memory of dried blood. And then he remembered, he'd never met his grandfather. But indeed he would, it was a long way back.

He rose to his feet a bit too suddenly though, and stumbled his arm against the trunk of a dogwood. The shock of pain shook his head clear, and he felt himself surface for a moment from the maze of delirium.

He had to find shelter, there was no use wandering this way in the dark. He looked around, but in the time he'd sat the foliage of the woods had gone from green to grey to a twilight blue that fell off quickly and went to pitch in the distance. The woods looked to open on a smallish hollow and he set himself in that direction. Dried pine needles crunched under foot and he could smell the familiar musk of pine rosin ripening in the July heat.

When he reached the clearing the maze of delirium had started to overtake him again and he groped like a shipwrecked rodent to try and stay afloat. He was standing in a large field surrounded by tall dry grass. When he decided finally to set himself down, he took to the grass as if it was a cozy bed of straw and went immediately to sleep.

Night descended thus, pushing away the remnants of the day and opening the sky to a pitiless and stark abyss.

Joseph remained tucked beneath the covers and listened as his mother's footsteps disappeared from the kitchen to be greeted by the deep voice of a man waiting for her in the living room. The slow music seeping down the hall receded beneath the closing living room door. Joseph could still just hear their muffled laughter rise and fall as he crawled from the sheets and settled at the foot of his bed. He pulled a tattered afghan up around his bony and pimpled shoulders. Outside his window the night was moonlit and quiet and he leaned slowly forward to touch his nose against the cold pane of glass. He rubbed his face slowly back and forth across the surface and sat back. Two exaggerated and hollow sockets stared back at him and beyond them he saw out and across the yard to the house next door. It was dark, dormant, and through one of its windows he could see clearly through to a window on the far side and out onto the yard beyond. He tightened the afghan under his chin. The tiny dot of the moon reflected in the warped and glossy scales of paint chipping in his windowsill, a hundred little stars caught in concave cages.

A short rolling giggle erupted from the living room and distracted him. He chose to ignore it and looked back out the window. He watched as the condensated likeness of his face slowly evaporated to leave a faint and distorted residue. And then something moved in the dark window of the house next door. Joseph leaned back out of the moonlight and watched. Two human shapes were moving in the shadows, their movement lurching, their silhouetted forms fluttering the way the shadow of a candle flame wavers and sputters under a dropping moth. They seemed to be dancing, entangled in one another, a man and a woman, and as they swept into clear view of the window, brushing and rubbing violently into one another, the moon revealed their nudity.

Joseph clinched his toes in the stitched holes of the afghan and closed his eyes tight. He stayed that way for a few minutes and when he opened his eyes, they were gone. The window was empty, the shadows still.

He lowered the afghan and slipped back into the sheets. The only sound was the slow music drifting from the living room. He tried to sleep but couldn't, and when he did finally close his eyes, it wasn't pleasant dreams that rose to greet him.

Tyson woke to find himself lying in the field of grass. His body was covered in dew and he could feel the heat of the sun steaming on his back. He tried to move, but his body was stiff and numb and his head started to tingle. He lay there, watching the flies gather on his arm. He watched them crawl across the dust and scabs, probing, perching on the little bits of glass. The glass glistened in the sunlight and mingled with a deeper and more threatening flicker, a swoon that swept across his vision and overtook him.

When he came to he could see just enough to know that he was lying in a different place. The tall grass sat off back away from the rock and red clay where he now lay. His vision was blurry, he felt dizzy. He couldn't move, his lips felt dry and cracked. But he could blink, and he did so, rapidly, as if his crying eyes might force tears to run in a coat over his lips.

His sight cleared and he saw how the grass grew around the clearing he was now in, surrounding him. The sun beat down relentlessly. At the far edge of his sight he could just barely see a small and dilapidated structure and he mustered enough strength to pivot his head.

The building looked like a small barn, long since retired, and in his delirium he imagined himself inside of it, cradled in its shade, lying in straw. He imagined the musk of it, and somewhere in that imagined aroma he could detect the hint of something he'd maybe forgotten long since, something maybe conjured by his withering condition, but he remembered it clearly, it was real to him: Himself, as a small child, playing in the straw loft of a barn as his father and his father's father worked outside in a bright and infinite field, a field that seemed to stretch out peacefully in every direction, surrounded by distant hills beyond which the sky hung in limitless blue possibility. The day gave way to night.

When he came back to he still lay on the ground. A few feet in front of him stood two skinny legs. They turned and walked away to grow into the figure of a boy standing with his back to him. He held Tyson's gun, curiously, as if contemplating its shape and design with practiced hands. He held the gun out from him and studied it against the backdrop of something Tyson couldn't see clearly. The boy leaned down and placed it confidently amidst what appeared to Tyson a pile of rusting junk. He tried to raise his head in protest but the heat of the sun and the blue of sky melded and sunk down on him in a sharp burst.

He slipped in and out, the sky going dark and overcast in bright flashes that skirted his eyes with silent lightening. He felt himself being dragged across the ground and looked up with just enough reason to recognize the face of the boy that lived down the street. His limbs were numb, his body cold, but he could feel the pressure of the boys hands pulling him under the arms. He slipped off and came back as the boy was struggling to pull him over a threshold. He saw his dangling legs kick against a door of rotting wood. They were entering the barn.

Inside it was dark, and Tyson thought he was passing out again before he noticed the windows and the light coming in. The boy lowered him to the ground and Tyson was able to see around, and it was then that he realized where he was: Beneath the crown of the palm tree, same as his father, the tattered fronds now smaller but hanging dark and weathered and swaying all around them, silhouetted against the windows like shredded strips of meat. The last thing Tyson felt was the subtle pressure of the boys hands on his ankles as he brushed away the flies and carefully removed his boots.

From John Randono

While many Turkish psych fans may already be familiar with Ersen's drum-heavy prog through fine compilations by World Psychedelic Classics and Finders Keepers, this album seems to have evaded those releases. I found it in Kadikoy, Istanbul, along with some choice 45's... this is the first cut off the second side entitled "Yagmur Duasi"... enjoy.

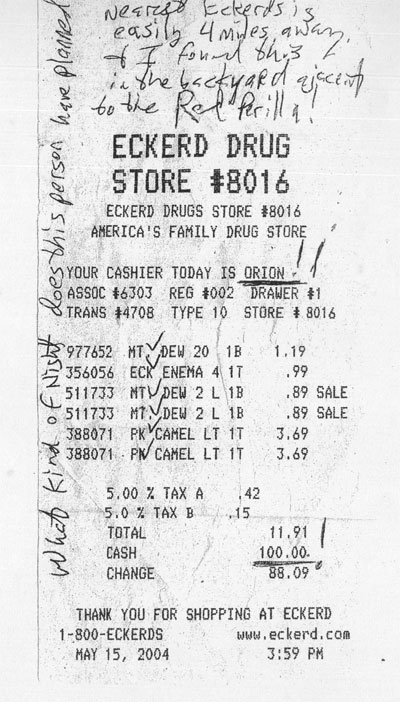

By J. Ryan Stradal

We know this much is certain: Rudy Shlomka wrote shopping lists. Perhaps the most important shopping lists ever written in English. Whether he actually went out and purchased anything on these lists is for the scholars and art critics to argue over. We at the Institute are interested in the facts.

We know that Rudy wrote his first shopping list in late 1982 shortly after moving out of his parents' house in Hastings, Minnesota. We also know that during his celebrated "Red Period" (from 1984-1986) he wrote up to three a week, which now sell for thousands of dollars, if you can find them. And yes, we know that we winced along with the rest of you over his maligned late 1980s works, when he began writing for his audience and not himself.

But we at the Institute are not content to be sad, even at the thought of losing one of the 20th Century's great artists to the perdition of excessive self-awareness. The shopping lists of Rudy Shlomka are, to some, "notes scribbled in the margins of the last act of Western Civilization" (Des Moines Register) or "the spit of a culture fatally poisoned by desire, but dying, ultimately, of boredom" (Le Monde) but to us, they're merely the work of a once-in-a-generation talent.

Shlomka, like Eno, Rothko, and Mondrian, responded to the manifold over-stimulations of his culture with a Spartan, even deconstructionist, impulse, but to call Rudy Shlomka a minimalist is to debase his work with historical context. As far as we know, his shopping lists are the only writing he ever did – and the only writing he ever needed to do. Shorn of verbs, adjectives, adverbs, and pronouns, they give us as stark and uncompromising an image of life as it is possible for a reader to emotionally withstand.

To wit, let's begin with one of his earliest pieces, January 14th, 1983. At the time, Rudy was working as a short-order cook at a restaurant called Perkins on Highway 61. He had moved out of his parents' house the previous November following a heated discussion with his parents on how he "needed to get his act together." He was living in a two-bedroom, two-bath unit above the Hastings Beauty School (now the Shlomka Museum) with a high school friend, one "Stube" Nieman (now Shlomka Museum curator). The list was as follows:

This list, which Bricolage Magazine called a "complete biography in eleven words," is a masterwork of human frailty and desire. The use of proprietary names bespeaks a unilateral, but charming, onset of materialism; at his then-precious age (19) the attachment to "name brands" may be an emotional harkening to the comforts of the home that so recently dispossessed him. We can also ascertain that his job as a short order cook may have obviated a need for domestic comestibles, hence "milk" and "corn puffs" as the only items of possible nutritional value.

The Certs and the condoms: Who are we kidding, that's a Friday night waiting to happen. And thus the Chap Stik (sic) would be necessary, particularly in southern Minnesota in January, when there are days you're advised to never expose your moist flesh to the cold, much less affix it to another person's.

This list is typical of this era. It is the brilliant early sketch of a genius coming into his own, yes, but it is also as pointed and actualized as anyone with fifty years of art training could devise, and believe us, they know that. Even the critics who were the first to say "Come on, anyone could do that" begrudgingly give a free pass to Shlomka's early work. At only 19! So brilliant, so simple, so effective. We all knew great things were to come.

Two events in mid-1984 inspired a dramatic evolution in Rudy's shopping lists. First, Rudy and Stube went in together on an air conditioner. This "is coterminous with O'Keefe's move to Abiquiu or Joyce's spell in Vienna as a tonic for personal and artistic growth" (Bricolage Magazine) and dramatically increased their time spent in the apartment, all the better for eating in. Second, Rudy switched to a red felt pen to write his (longer and more numerous) shopping lists. As in the classic July 9th, 1984 (courtesy of the estate of Eric Clapton):

This list, which inspired the Nobel Prize-winning essay I Hope The Tacos Were Good, is regarded by many as Rudy Shlomka's Guernica, his Ulysses, his OK Computer. Where do we begin?

For starters, let's look at #2 on the list. Some lucky woman, wooed by the Certs and condoms, has now insinuated herself in his life so effectively that Rudy has written "maxi-pads" second on his list, in his own handwriting, and if we could show you the real list we would (it's on loan to Carnegie Mellon University) and you would see that there are no skips, halts, or nuances in the handwriting that apparently differentiate those two words from the others on the list. This speaks of a man comfortable with the idea of buying feminine hygiene products, indicating either a comfortable devotion or unhealthy obsession with said speculative female, whose identity is unclear.

Now, several women have come forth, claiming to be the recipient and user of the Rudy Shlomka-bought sanitary napkins, but the Institute has no interest in such conjecture. Yet, most art historians now believe the most likely recipient is Katie Nitwanger (nee Kranchick), despite the public and vehement exhortations of Misty Schwermer Shlomka, notably in her 2005 memoir "Listless."

Critics point out that whatever Rudy's connection to his regular female companion during this era, the feminine hygiene product is still second on the list to "PBR". So.

One other item of note, and then we move on. Nail Clippers. Right there among the taco ingredients. This modest hiccup amidst reason has had board-certified taxonomists saying "what the fuck?" for the better part of a decade. To many of us, this is not just Rudy pausing circumspectly at the thin line between personal hygiene and throwing a kick-ass taco party; it's so much more.

So few of us can describe the definitive moment we became an adult; we struggle to recall one instance of action or agency that divorced our impulses from those of a hormone-ridden beast. These two words, "nail clippers," is one such moment, where an inkling of greater need has broken the fevered anticipation of ephemeral desire. At that moment, one young man leapt into a world where having clean, clipped fingernails was more important than lettuce for tacos. If only we could all be so lucid.

The next few years were a Golden Age for Rudy Shlomka, professionally and personally. He was promoted first to Night Shift Manager, and four months later, Day Shift Manager at Perkins. He married the former Misty Schwermer, a popular day shift waitress known for her winning smile and shaved crotch. She moved into the two bed/two bath apartment he shared with Stube Nieman, who initially agreed to the arrangement, until he learned that they intended merely to split Rudy's half of the rent rather than divide the rent in thirds like Stube assumed. Piqued, Stube declared his intention to acquire his "own fucking place." Around this time – April 1987 – Rudy composed a shopping list that Strophe Magazine proclaimed as "his White Album, perhaps even his Metal Machine Music":

No one had ever seen Rudy write a list like this before. It split his fans; the new converts wanted more lists of chemicals and cleaning supplies, while his loyal base denounced the evolution and secretly hoped for a return to his earlier, more accessible grocery lists.

"The PBR at the bottom gave us hope," said Shlomka collector Janice Ivy. "It's the inevitable sum in the Fibonacci sequence of his life."

Others were less forgiving, such as Dr. Dune Howly, chair of the Artistic Department at the University of Calgary, who wrote in The National Delineator: "His use of proprietary names is hackneyed and cheap, especially at his advanced age [24]. This has all the signs of a desperate grasp for artistic validation, presaging a sudden decline."

Arguments over when the sudden decline began, or just how sudden the decline was for a "sudden decline," are no concern of the Institute. Yet we were shocked along with the rest of the world when this list, dated February 1988, appeared in an exhibition:

The reviews echoed the fans' disappointment. "Terrible," wrote the Cleveland Plain Dealer, "And too short by a half." "Only one brand name?" remarked the Spokane Decider. "He's listening too much to his critics." "We don't like the direction he's taking," Janice Ivy wrote in the Pasadena Instigator. "Where's the PBR?" "Sellout," said Rolling Stone.

Like the baseball cards of a veteran pitcher who should've unknowingly taken steroids, Rudy's grocery lists decreased in value. But even during what his fans called the "Fat Elvis stage" of Rudy's career, they never gave up hope. They stood out in the rain for exhibitions they knew would be disappointing. They imitated his lists at the supermarket to the point that two chains (Red Owl and Lucky) set up "Rudy Shlomka" aisles. Sometimes they would make votive candles out of bisected PBR cans and hold vigils outside the Hastings Beauty School, doing readings of his lists late into the evening, even on school nights.

We at the Institute do not know for sure when Rudy Shlomka finally became aware that his shopping lists were a sensation in the found art community, but available evidence points to summer or fall of 1988. From the adjunct professor in Cultural Anthropology who found "List #1" on the ground, to the collectors who rifled through the trash cans outside of supermarkets, to that secret cadre of grocery baggers who called themselves "The Relentlers" – museums and galleries had manifold conduits to Rudy's art without Rudy's knowledge or intervention. One unscrupulous curator went so far as to bribe Stube Nieman, whose price was reported to be astonishingly low. Others resorted to even more intrusive and criminal acts.

Reeves Shaw, the visionary behind Toronto's Portmanteau Gallery, wasn't known for his clumsiness. However, his unsolicited early-morning visit to Rudy's apartment on January 20th, 1989, altered the art world's relationship with Rudy Shlomka forever.

The next morning, Rudy was seen leaving a piece of paper behind at the Don's Super Valu in Hastings. It read as follows:

"Leave me the fuck alone. Quit breaking into my house and stealing my shopping lists. For months you have been upsetting my wife Misty and now my young son Kirby. And my patience is WORN OUT. Quit exhibiting my private crap in the Whitney, or I will bust your ass. Signed, Rudy S."

(Courtesy of the Whitney Museum permanent collection)

"His most disappointing work to date," wrote Peter Nitwanger for the Minneapolis Star-Tribune. "He broke all the concrete Rudy Shlomka rules – verbs, pronouns, punctuation, direct address. All that, and his use of profanity, doomed him in the eyes of an audience looking for stimulation, looking for novelty."

"Rudy got Ewok Syndrome," Janice Ivy elaborated to Ed Bradley of 60 Minutes, reflecting a widely held opinion. "His wife popped out that fat obese kid and the quality of his work went straight into the toilet."

Most of Rudy Shlomka's audience agreed with Ivy. It was as though Jimi Hendrix came back from the dead just to play Guitar Hero. His fans, once merely disappointed, were now furious. They pelted his home with items purchased in the Rudy Shlomka aisles of their local supermarkets. They burned copies of his shopping lists. Nutritionists like Edgar Caquill fell over themselves to criticize a diet heavy on beer and tacos.

Rudy refused to go out in public, sending Misty to do the shopping. Her lists were considered derivative but attracted a small cult following. One day in the condiments aisle she was approached by a man who said that he'd pay her to write his grocery lists for him. We at the institute can't confirm this, nor do we care to, but it's rumored that this man was former Metallica bassist Jason Newsted. He is said to have swept Misty off her feet; she and Kirby never returned home.

While we at the Institute prefer the Cliff Burton-era Metallica, we do not intend to point fingers over what happened next. On September 4, 1992, Rudy left another note in the cereal aisle of Don's Super Valu, and it would be his last.

"Alright. You people have destroyed my life. First you prevent me from doing my own shopping, and then you send Metallica to seduce my wife. Well you're [sic] evil plan worked. Misty is divorcing me for and taking our "fat obese" son Kirby with her. So I am leaving Hastings for good and I won't say where. All I can say is that I hope you people are fucking happy. All these years, I just wanted to buy some groceries. Was that too much to ask? I guess so. Signed, Rudy S."

(Courtesy, Shlomka Museum)

The last we at the Institute heard, Rudy Shlomka was living in a sustainable permaculture co-operative in Mendocino County, California, and hasn't intended to buy anything in a store since 1993.

Someday, we're certain he will emerge from this John Lennon/Miles Davis-esque exile and come back to our world to purchase things once again. The guesswork as to what, and when, has already begun, but not by us here at the Institute. No, we will simply wait patiently – like everyone in this room – for the day when we learn, once again, what Rudy Shlomka plans to buy.

By Marc Minsker

Man is going to be displaced altogether as a specialist by the computer. Man himself is being forced to reestablish, employ, and enjoy his innate comprehensivity. Coping with the totality of Spaceship Earth and universe is ahead for all of us.

- Buckminster Fuller, 1963

Why join the navy if you can be a pirate?

- Steve Jobs, 1987

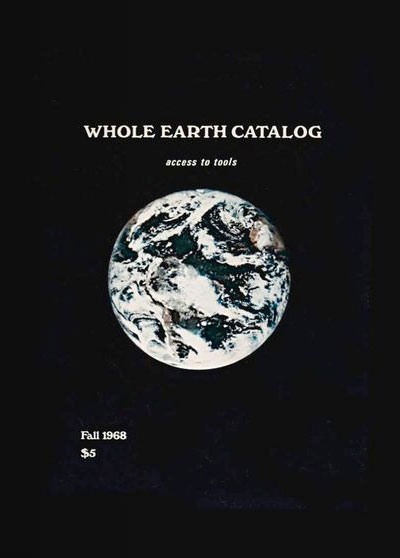

Ignoring all of the hippie nostalgia and summer of love sentimentality, the late 1960s saw at least one creation that promised to truly revolutionize the world. It wasn't Apollo 11 and it sure as hell wasn't Woodstock. It wasn't the consumption of LSD nor was it the rise of the Black Panthers. Although these may have channeled some sense of revolution, the truly innovative creation of the 1960s was a 96-page, oversized, black and white publication printed on newsprint. In a quiet and subtle way, it had the potential to change the world forever: The Whole Earth Catalog.

From the beginning, the mission was simple: To "empower the individual...[because] so far, remotely done power and glory—as via government, big business, formal education, church—has succeeded to the point where gross defects obscure actual gains. In response to this dilemma and to these gains a realm of intimate, personal power is developing—power of the individual to conduct his own education, find his own inspiration, shape his own environment, and share his adventure with whoever is interested. Tools that aid this process are sought and promoted by the Whole Earth Catalogue."

Conceived by biologist Stewart Brand as a way to level the playing field for all humans on the planet regardless of one's socio-economic background, the Whole Earth Catalog (WEC) was published in Menlo Park, CA, by the Portola Institute. The first publication was designed in a 11x14 format with a single color image residing on the front page: an awe-inspiring image of Earth taken by NASA. In an ingenious form of branding, Stewart Brand used the rarely seen view of the Earth to further his hyperbolic claims that the catalogue contained everything under the sun. The synthesis of idea and image was pure genius. 38 years later, Apple Inc. would appropriate this image and form of branding for their "revolutionary smartphone" known as the iPhone. Steve Jobs himself has described the WEC as an analogue for the internet, in particular as a precursor for Google, which coincidently started in Menlo Park as well. But this analogy is far from sound, and Jobs as well as millions and millions of humans have been duped if they think an iPhone can empower them in the same way as the WEC.

The WEC had the potential to make us autonomous; the iPhone, automatons. With its "access to tools" to aid in facilitating everything that a human seeking autonomy on this planet might need, the WEC contained a smorgasbord of "how to" products and information: how to filter dirty water, how to build a safe and affordable shelter, how to find edible plants and seeds in the wilderness, how to construct a Buckminster Fuller designed geodesic dome with recycled materials, how to grow mushrooms, how to read Tarot cards, how to make your own moccasins, how to design a sailboat or a glider plane, how to fuck a rabbit...

Entries were arranged by elemental human categories (Industry and Craft, Whole Systems, Communications, Nomadics, Shelter/Land Use, Community, and Learning) and sections were usually offset with snippets of poetry or compelling imagery.

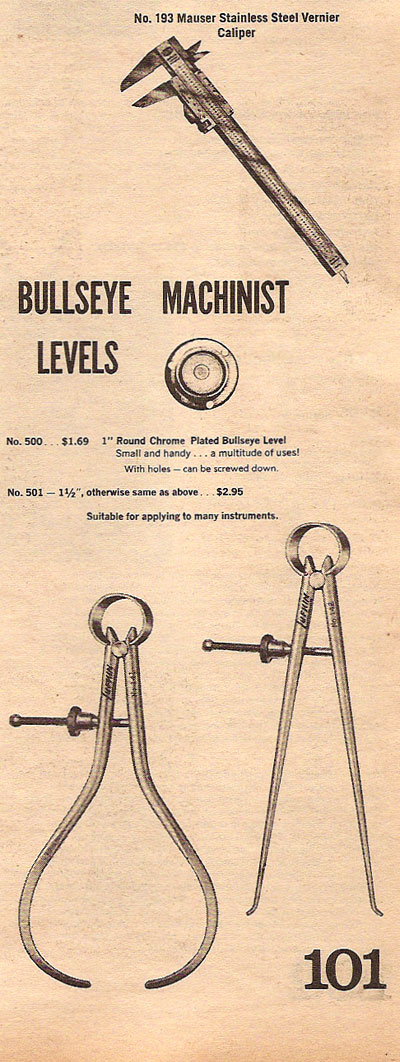

For those uninitiated in the ways of the WEC, it is important to understand that the publication wasn't a catalog in the typical sense: that is, a catalog simply full of advertisements for products and goods. Each entry contained a lengthy excerpt from the work or an essential diagram that, in itself, was useful to the reader. For instance, an entry for a 25 cent publication titled BUILD A LOG CABIN (from the Fall 1970 edition) included half a page of schematics on how to notch the logs and how to frame the upper rafters. More often than not, these diagrams were educational and helpful, even without ordering or seeing the item in its entirety. And unlike typical catalogs, which contain products exclusively from L.L. Bean or Sears, the WEC provided consumers with direct purchasing power, thereby cutting out the department store or the middleman. For the first time in free market capitalism, people could buy directly from the manufacturer or the poet or the craftsman or the scientist, making well-informed decisions based on the wealth of information in the pages of the WEC. Then, on the merits of one's hands and minds alone, a WEC subscriber could build, maintain, and enjoy technology in a satisfyingly self-sufficient way.

Although Apple would like to cast the iPhone in a similar light, touting thousands of Apps that "make living easier," the plain and simple truth is that its subscribers are at the mercy of the service and data plans, the cell coverage, the battery, and the circuitry of the phone itself. Remove any one of the iPhone's contingencies, and the subscriber ends up without a single tool. Not even a timepiece.

Sure there is a slim chance the unlucky bastard could fornicate with a rabbit, if they could figure out how to catch one, but even that is improbable.

i lost you, my white stallion; where are you? it's winter, i am covered with white snow. the white knot - this time it does not come undone. i wanted to ride you into town. snow-silence of white stallion - runneth away into the prairie. and the prayers, gone up in smoke - stallions. i swim, i swim. white, white, like lattice whitewash, i lost you, my white stallion.

singularly terse poetics grandiose salivary

snow-white mustang knee deep in immature estrogen

snow: white of the death unaccepted postmortem

answer the polyphone call

I love the interplay with Celan here. The problem is the song is in Russian. It's a very famous song, super-sentimental/verbose, about a tzar-time Russian officer losing his white stallion. He sings that he wanted to enter the town on his white horse, but on the way there he was seduced. The horse was weeping for him while he was fucking this woman (it's a very romantic description of the act.) In the morning, the horse was gone.

By Dimitri Mittens

by my window I have for scenery just

a sea

the canary

and Madonna

buongiorno, fellows of the royal infinity

morning

blue pinstripes

touch softly nature's sweet guitar

seatalia slowly slowly

at my window

singularly terse poetics grandiose salivary

snow-white mustang knee deep in immature estrogen

snow: white of the death unaccepted postmortem

answer the polyphone call

By Dimitri Mittens

starting from the orchis -

aspectral, the light of your flower bestows itself and fills: my heart with angel songs, my soul - with so much love. beautiful, to be veiled by nothing, you cast them, loveshadows.

joytear river drooping into the delta.

where do i begin, orchis and orchis, singly,

to tell the sweet love story into the sea.