Facsimile Magazine, Published by Haoyan of America. Volume Three, Number Five, 2009. ISSN 1937-2116.

Facsimile May 2009 ~ Apparent Meanings Became Implied

Table of Contents

Facsimile Magazine, Published by Haoyan of America. Volume Three, Number Five, 2009. ISSN 1937-2116.

Table of Contents

From The Art And Popular Culture Encyclopedia, Fusion Anomaly, Planet Bowles, Ubu Web, and Wikipedia

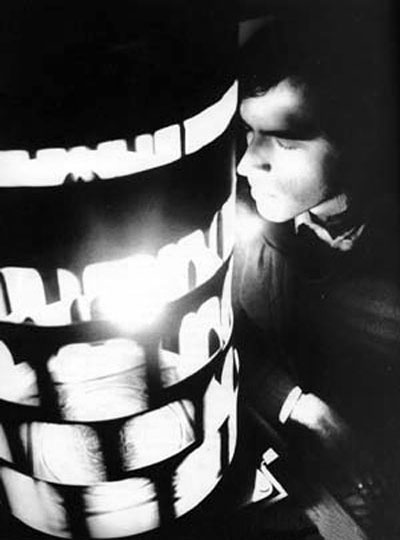

Brion Gysin rests in a Tangier hospital bed following a motorcycle accident in which he lost two toes. Photo by Shepard Sherbell

Brion Gysin (1916-1986) was a painter, writer, sound poet, set designer, and performance artist born in Taplow, Buckinghamshire.

He is best known for his discovery of the cut-up technique used by William S. Burroughs. With Ian Somerville he invented the Dreamachine, a flicker device designed as an art object to be viewed with the eyes closed. It was in painting, however, that Gysin devoted his greatest efforts, creating calligraphic works inspired by Japanese and Arabic scripts.

The painting of Brion Gysin deals directly with the magical roots of art. His paintings are formulae designed to produce in the viewer the timeless ever changing world of magic caught in the painter's brush - bits of vivid and vanishing detail... The pictures constantly change because you are drawn into time travel on a network of associations. Brion Gysin paints from the viewpoint of timeless space.

- William S. Burroughs

Gysin spent much of his life between Morroco and Paris. In 1954, he co-founded with Mohamed Hamri a restaurant called "The 1001 Nights". Situated in a wing of the Menebhi Palace in Tangier, it became a very popular place to dine for both Moroccans and expatriates alike. The cuisine was exquisite and the walls of the restaurant were covered with Gysin's artwork of the Moroccan and Algerian Sahara deserts, which he had visited extensively. Jane and Paul Bowles, along with other local notables, such as William S. Burroughs, used to often frequent the 1001.

Gysin's entertainment usually featured a fire eater, a Moroccan orchestra and cabaret dancers, all of whom had been brought up from the Ahl Serif tribe in the mountains, about 90km south of Tangier. He would also use the restaurant to showcase the talents of his Moroccan "house band" - The Master Musicians of Joujouka.

Gysin and Hamri played a large part in bringing The Master Musicians of Joujouka to the attention of westerners, most notably through their contact with Brian Jones of the Rolling Stones.

The three of them, along with an Olympic Studios engineer, George Chkiantz visited Joujouka to record an album of music, which became the first LP of The Master Musicians of Joujouka. Released in December 1971, it was called "Brian Jones presents the Pipes of Pan at Joujouka." For Jones, the experience was to dominate the last year of his life. His obsession to incorporate the music of Joujouka into the Stones's sound was yet another factor that distanced him from Jagger and Richards. The artwork on the original album was created by Mohamed Hamri in 1969 and the introductory notes were written by Brion Gysin.

After the closing of "The 1001 Nights" in 1958, Gysin returned to live in Paris, taking lodgings in a flophouse located at 9 Rue Gît-le-Coeur that would later become famous as the Beat Hotel. While working on a drawing, he discovered a Dada technique by accident:

William Burroughs and I first went into techniques of writing, together, back in room No. 15 of the Beat Hotel during the cold Paris spring of 1958... Burroughs was more intent on Scotch-taping his photos together into one great continuum on the wall, where scenes faded and slipped into one another, than occupied with editing the monster manuscript... Naked Lunch appeared and Burroughs disappeared. He kicked his habit with apomorphine and flew off to London to see Dr Dent, who had first turned him on to the cure. While cutting a mount for a drawing in room No. 15, I sliced through a pile of newspapers with my Stanley blade and thought of what I had said to Burroughs some six months earlier about the necessity for turning painters' techniques directly into writing. I picked up the raw words and began to piece together texts that later appeared as 'First Cut-Ups' in Minutes to Go.

- Brion Gysin

The chance discovery by Gysin of the cut-up technique (later developed and refined by Burroughs) and the concept of permutated poems gave rise to new and original forms of sound art wordplay, striking not only in print but also in recordings and live performance.

By treating segmented pages of text as collage material, the new arrangements created limitless possibilities of prose. A second seminal technique pursued by Gysin was one of a more focused and elegant nature: the permutation. By taking a single phrase and running through all existing possibilities of order, whole realms of implied meanings became apparent.

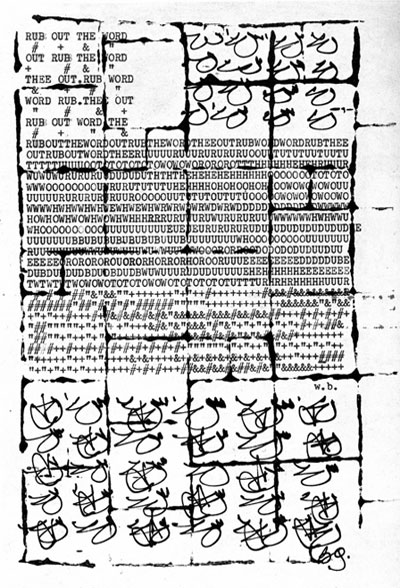

Rub Out The Word, Brion Gysin and William S. Burroughs, 1965

When Burroughs returned from London in September 1959, Gysin not only shared his discovery with his friend but the new techniques he had developed for it. Burroughs then put the techniques to use while completing Naked Lunch and the experiment dramatically changed the landscape of American literature. Gysin helped Burroughs with the editing of several of his novels including Interzone, and wrote a script for a film version of Naked Lunch which was never produced. The pair collaborated on a large manuscript for Grove Press titled The Third Mind but it was determined that it would be impractical to publish as originally envisioned. The book later published under that title incorporates little of this material.

From working on canvas and paper, Gysin took the obvious continuation of his ideas to audio tape. With the help of his mathemetician friend Ian Sommerville, cut-up and permutated recordings demonstrated the true potential of those theories. Audio cut-ups presented the startling impact of linking words, sounds and time through juxtaposition. The development of the audio permutiation poem added variablility through spacing and inflection which provided characteristics that were impossible on the printed page.

In 1960, Gysin was asked to present sound works for broadcast on the BBC. Among those recorded for the event were "I Am That I Am," "Recalling All Active Agents," and the "Pistol Poem" which differed by permutating recordings of a gun firing at varying distances. In 1969, Gysin completed his first full-length novel, The Process, a work judged by critic Robert Palmer as "a classic of 20th century modernism."

There was something dangerous about what he (Brion Gysin) was doing.

- William S. Borroughs

Though popularly attributed to Brion Gysin, the Dreamachine was invented by his friend Ian Sommerville, who passed away before the device would be fetishized for its popular occult associations. Sommerville created the Dreamachine based on principles outlined by pioneer physiologist William Grey Walter in the chapter, "Revelation By Flicker," from his book The Living Brain. Gysin was the main exponent of the Dreamachine.

In its original form, a Dreamachine is made from a cylinder with slits cut in the sides. The cylinder is placed on a record turntable and rotated at 78 or 45 revolutions per minute. A light bulb is suspended in the center of the cylinder and the rotation speed allows the light to come out from the holes at a constant frequency, situated between 8 and 13 pulses per second. This frequency range corresponds to alpha waves, electrical oscillations normally present in the human brain while relaxing.

A Dreamachine is "viewed" with the eyes closed: the pulsating light stimulates the optical nerve and alters the brain's electrical oscillations. The "viewer" experiences increasingly bright, complex patterns of color behind their closed eyelids. The patterns become shapes and symbols, swirling around, until the "viewer" feels surrounded by colors. It is claimed that viewing a dreamachine allows one to enter a hypnagogic state. This experience may sometimes be quite intense, but to escape from it, one needs only to open one's eyes.

In 1985, Gysin was made an American Commander of the French Order of Arts and Letters, he died a year later on July 13, 1986 of lung cancer. An obituary by Robert Palmer published in The New York Times fittingly described him as a man who "threw off the sort of ideas that ordinary artists would parlay into a lifetime career, great clumps of ideas, as casually as a locomotive throws off sparks."

Brion Gysin's wide range of radical ideas became a source of inspiration for Beat Generation artists and their successors such as John Giorno, David Bowie, Keith Haring, Patti Smith, Lauri Anderson, Michael Stipe and Genesis P-Orridge. Interviewed for The Guardian in 1997, Burroughs explained that Gysin was "the only man that I've ever respected in my life. I've admired people, I've liked them, but he's the only man I've ever respected."

Of course the sands of Present Time are running out from under our feet. And why not? The Great Conundrum: 'What are we here for?' is all that ever held us here in the first place. Fear. The answer to the Riddle of the Ages has actually been out in the street since the First Step in Space. Who runs may read but few people run fast enough. What are we here for? Does the great metaphysical nut revolve around that? Well, I'll crack it for you, right now. What are we here for? We are here to go!

- Brion Gysin, The Process, 1969

By Tom Furtsch (with lots of help from Maitland A. Edey and Donald C. Johanson)

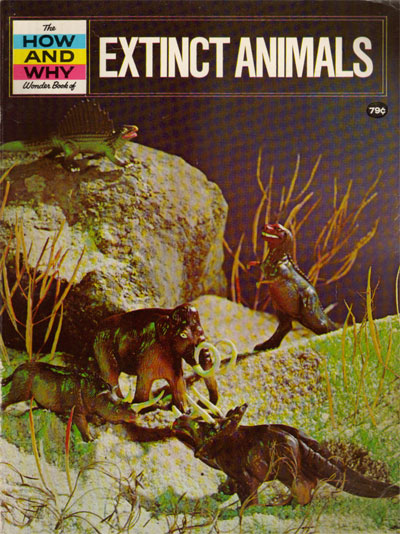

The How And Why Wonder Book of Extinct Animals, 1972

As we consider what science might accomplish in the 21st century and/or what we expect of science in the 21st century, I would like to share some thoughts with you. I was loaned a book a short while ago which reviews the events and mysteries of evolution. The book, Blueprints by Maitland A Edey and Donald C. Johanson, is worth your reading if you have any interest in evolutionary theory. It was Johanson you may recall who was the discoverer of one of the so called "missing links" in human evolution, the skeleton called "Lucy". These old bones, thought to be about 4 million years old, and now known as Australopithecus Afarensis, represent a person that is now thought to be the earliest known link in the evolution of man after separating from the apes. The information we have about these old bones is changing rapidly with new discoveries.

I was particularly struck by the last chapter of the book which has the intriguing title "Is There Danger In Being Too Smart?". What follows is a summary of some of the ideas and conclusions in that chapter. At the risk of changing some of their ideas, this is my own synthesis of the chapter with a few quotations thrown because they say it better than I could.

"The human brain is a truly extraordinary instrument. It allows a living creature, for the first time in the history of life, to contemplate itself (herself/himself ), to gain some knowledge of our origins, of the planet on which we live, and of the universe of which our planet is a part. All earlier life has been utterly ignorant of these things. The human brain does more; it allows us to alter our environment for our own benefit in ways no other creature has ever done--indeed it gives us awesome power to do that."

The general theme of the chapter is the thesis question, "can this oversized brain of ours carry a hidden danger?" In terms of evolutionary thought, is being smart an overspecialization which will ultimately drive us to extinction? Or will something else. Extinction is a part of life. Of all the species that have ever lived on the earth, more than 99% are gone. Two million years from now most of the species that now exist, will be gone. Will humans still be here, barring some catastrophe? We could be. After all, the dinosaurs populated the earth for over 160 million years. However, recent research has shown that mass extinctions do take place once in a while and seem to take place at fairly regular intervals. One can envision natural mechanisms for extinction such as extreme volcanism that cruds up the atmosphere shutting out the sunlight. Or an outside force such as a large meteor impact or comet, such as has just been speculated about in the media, or the earth passing through a very dusty part of the galaxy. Small extinctions take place regularly; mass extinctions only once in a great while.

But what of overspecialization? Edey and Johanson discuss what this means in terms of two examples of specialization. One, the case of the "English Sparrow" (not really a sparrow at all) which was brought to the United States in 1853 in an effort to get rid of the canker worms which were eating away the forests. These birds, fast breeders, chose not to eat many of the canker worms, instead finding it easier to eat food supplied them by humans. They ate seeds. As long as planting and farm animals were prevalent the sparrow population exploded. They quickly drove out native species of bird some of which never recovered. By the end of the 19th century it was the most numerous species in the country. Why was it so successful? The main reason was that it was extremely adaptable. It could live anywhere and eat anything humans ate. It was a generalist in terms of evolutionary parlance. We humans are its specialization.

Edey and Johanson compare the English Sparrow to the Kirtland Warbler, a specialist whose habitat was areas of burned out forests in one small section of Michigan. They only breed among the low scrub pines which took the place of the former forests and have found themselves in a more and more crowded habitat. There was no way of predicting that its habitat would become disastrously small. Today there are only a few of them left. If its habitat disappears, so will this warbler. Many extinctions have taken place in recorded history and are happening even as we speak today.

If the aim of life is to perpetuate ourselves, why would these birds allow themselves to be crowded into as small a habitat. Why was one of these birds so successful and the other so unsuccessful? In truth, neither the Kirtland Warbler or the English Sparrow had any say in the matter. Each was following a path provided to them by accident. The accident is the place you find yourself, quite by chance. If its habitat is too small or if it shrinks for reasons beyond your control, the species may be doomed to extinction.

Edey and Johanson give many other examples but more interesting to me, are their thoughts on the future of humans. So, let's ask their question again: "Can an oversized brain carry a hidden danger? Is it an overspecialization?" Most of us would quickly say certainly not. Our ability to think allows us to be physically unspecialized. We are the best of all generalists. We live anywhere, can provide for our own warmth and food. We can defend ourselves. We don't need to be strong even though many animals see better than we do and we cannot run as fast as many other animals. But using our wits we can out perform all other animals in every way.

But, Edey and Johanson point out, our culture provided by our oversized brain, is outperforming (evolving faster than) its inventor. Physically we have not changed in the last twenty thousand years. It took us half a million years to progress from the use of fire to achieve the ability to grow and produce our own food. Another ten thousand to figure out how to get metals from the ground to make tools. Two thousand more to learn to read and write, another thousand to develop explosives, a few hundred to perfect the internal combustion engine, a hundred to harness electricity, a generation to harness the atom and a decade to invent computers small enough to hold in your hand and do millions of calculations in a minute. We have learned where we came from and how we came into being and why we die. Now we are almost capable of redesigning ourselves. We may be able to redesign our emotional profiles. We pose ethical questions about how to use this ability we are developing but we are progressing so fast culturally that we may progress technologically further than our ability to manage that technology.

We are in danger of damaging our habitat beyond our ability to stop our own extinction. This has been going on for a few thousand years but we are only just recognizing that fact. Green areas are disappearing, air and water pollution is increasing, nuclear wastes are increasing at alarming rates, and the human population is increasing exponentially. We are using our sources of energy at a rate which will make oil pumped from the ground almost obsolete within the next 50 years. Is there a way out of our sure demise? I suspect we will figure out how to keep ourselves warm but I'm not sure.

Edey and Johanson's solution to this is that we will have to get ourselves out of this mess by applied genetics. That is we should make better people by using our technology to accomplish genetic change. If we do this we will need a new definition of evolution, one defined not by chance but by choice.

There is no doubt in my mind that the very basis of our problems lies in over population of the planet which puts tremendous stress on our habitat. Every other problem is a direct result of this overpopulation. We cannot control, to any great degree, when we die, but we can control when we are born. At some point in time, probably sooner than later, such stress will be applied to our system that it will react in some drastic way so as to relieve the stress (Le Chatelier's Principle) The results may be catastrophic for us as a species. Our brain is our only advantage, our specialization. Using it wisely is our only hope for prolonging our inevitable extinction.

Your comments are welcomed. Tom Furtsch

From Wikipedia

Nothing, Arizona. Photo by Vallarue

Nothing is a concept that describes the absence of anything at all. Colloquially, the concept is often used to indicate the lack of anything relevant or significant, or to describe a particularly unimportant thing, event, or object. It is contrasted with something and everything. Nothingness is used more specifically as the state of nonexistence of everything.

Grammatically, the word "nothing" is an indefinite pronoun, which means that it refers to something. One might argue that "nothing" is a concept, and since concepts are things, the concept of "nothing" itself is a thing. This logical fallacy is neatly demonstrated by an old joke that contains a fallacy of four terms: if nothing is worse than the Devil, and nothing is greater than God, then the Devil must be greater than God:

This can be argued to be true or untrue in fact, but its purpose is to demonstrate a play of logic.

Clauses can often be restated to avoid the appearance that "nothing" possesses an attribute. For example, the sentence "There is nothing in the basement" can be restated as "There is not one thing in the basement". "Nothing is missing" can be restated as "everything is present". Conversely, many fallacious conclusions follow from treating "nothing" as a noun.

Modern logic made it possible to articulate these points coherently as intended, and many philosophers hold that the word "nothing" does not function as a noun, as there is no object that it refers to. There remain various opposing views, however—for example, that our understanding of the world rests essentially on noticing absences and lacks as well as presences, and that "nothing" and related words serve to indicate these.

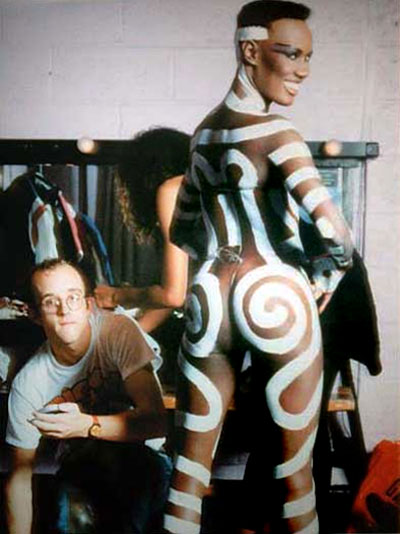

Keith Haring painting Grace Jones's body. Photo by Tseng Kwong Chi

All serious people seem to have a good sense of nonsense, as opposed to earnest people, who don't know what to make of nonsense. Today, there are too many earnest people in the arts and not enough serious people.

- George Rose

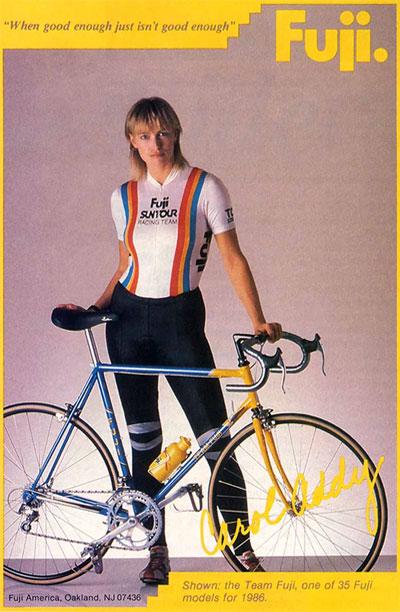

Carol Addy road-raced at national level in the '80s. I believe she did well, but I don't really know. I wasn't a fan; I was an admirer. I had a huge crush on her.

She was on this Fuji poster you saw in shops. She was standing behind her bike wearing her Fuji-SunTour jersey and a pair of ankle-length tights. I worked in a Fuji shop. I looked at the poster. I thought, "Oh my. That woman is SO hot. They must print that poster on glossy asbestos."

I only saw Carol Addy once, one of the years the East Coast bicycle trade show was in Atlantic City. Eastern shows were quiet enough so you could take breaks. You could wander outside onto the famous boardwalk. My friend Donald Dickson and I did that. We walked outside, bought coffees and sat on a bench facing the Atlantic, chatting, smelling the salt air.

We saw Carol Addy standing, elbows on the railing, gazing out over the ocean. She was wearing sunglasses, a trench coat and heels. She didn't look like a bike racer or a gambler. Or perhaps she did look like a gambler, a Bond movie princess playing baccarat in an elegant Monaco casino.

She looked like royalty hiding behind sunglasses, or a Burberry raincoat model waiting for a photographer.

We watched as she studied the white-capped waves and endless rolling distance. She was as lovely and mysterious as the sea, as Garbo ever was or was photographed to be.

I imagined her thinking about the handsome prince who was her suitor and her family's favorite, and the equally handsome but more sensitive playwright who adored her too.

She was probably thinking about how much her feet hurt, standing on the show floor all day in those pumps.

Donald and I thought our thoughts and said nothing. We certainly said nothing to her. He and I still reminisce about that day, the sun shining through the spray, the stunning woman leaning on the rail.

I heard rumors over the years that Carol Addy was going to medical school. A check on the 'net' revealed that, yes indeed, she's a doc now at a major Massachusetts hospital. Lives in Boston, is the word. Someone said she ran the Marathon.

I have no idea if she's married or single, but if it's the former, I hope she married the playwright.

Actually, that's not the end of the story. Encouraged by my editor, I called the hospital and left a message for Doctor Addy. When she returned my call, I read her this piece. She felt flattered by it, she said.

Her bike racing memories seem to come from another lifetime, she told me. She remembered the Atlantic City show clearly. She didn't know him at the time, but her future husband was there, working a nearby booth. He too had been noticing Carol Addy. He followed up on his interest, by golly.

So she didn't marry a writer, as she might've in the fantasy life I'd invented for her. She does still ride her bike but her primary exercise is running, because of time pressures, and she did finish the Boston Marathon.

Take a look at the old Fuji poster. Still looks great, doesn't it?

From the days of seven gears and Benotto tape, the poster that launched a thousand Fuji orders. Lovely Carol Addy: bike racer, doctor, gazer at oceans.

Lee Harvey Oswald funeral, Nov 25, 1963

In the church sanctuary

42. White male. Unmarried,

The simple casket, pine and brass handles, there lays

As the mother and father watch in black, dark greys

The pews polished and clean

Ready for mourners, but attendance is lean

Very few friends or acquaintances come

Their thoughts and feelings of grieving mum

Sorrow and shame intermingle to make sand,

Although it is not up to them for him to be damned,

Cards, loves, wreaths of fresh flowers

Justice, not vengeance, they are all vowers

Tears and sound bites flow

All believing humanity must have reached at an all time low

Did you know him?

Yes, he was a great man. My best friend.

How many best friends can one man have?

Is there anything bad said of those who have died young, accidentally, or intentionally by the hand of another?

Phalanxes of the sorrowful line the block

Harder to sympathize than mock

Caught up in the media spotlight

Crying over the unknown dead seems so trite

The victim’s funerals are much different

Than those of the perpetrator.

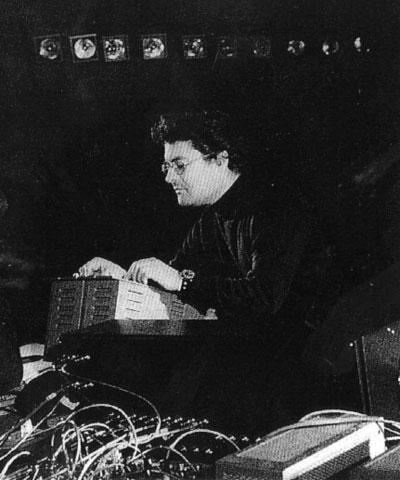

By John Diliberto, From Electronic Musician, December 1986

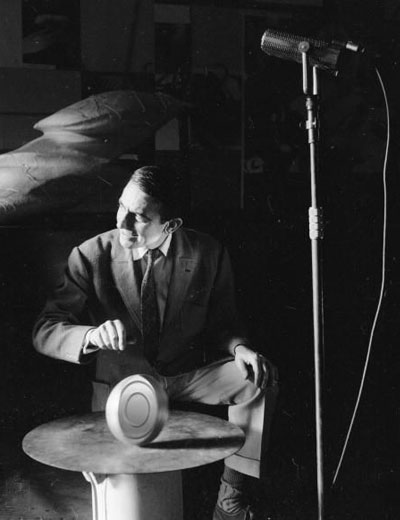

Pierre Schaeffer developed the genre of musique concrète: tape music using collages of recorded sounds. Photo by John Sadovy

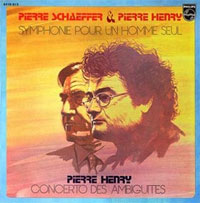

Before Trevor Horn sampled a sound, Alvin and the Chipmunks squealed, or Run-DMC scratched a record; when synthesizers were a twinkle in the imagination of Varese and Cage and at about the same moment that Eno formed his first infant gurgles, Pierre Schaeffer and Pierre Henry (pronounced: Ahn-ree) were transmuting the world of sound. In the mid-'60s, their techniques were arcane: by the early '80s they were nouveau-chic. But in 1948, they were revolutionary.

"Our direction was to turn our back on music and that is crucial," proclaimed Schaeffer in his elegant, old Paris apartment. "People who try to create a musical revolution do not have a chance, but those who turn their back to music can sometimes find it."

Shortly after World War II and shortly before the widespread use of magnetic tape (developed in Germany), Schaeffer and Henry began their revolt by recording sounds from the natural world onto phonograph discs, altering them through the primitive means available, and creating an alarming music that they dubbed musique concrète (pronounced: muzeek kon-kret), or concrete music.

Think of The Art of Noise without a rhythm box and you have a rough approximation of the first masterpiece of musique concrète, Symphonie Pour Un Homme Seul (Symphony for a Man Alone), Schaeffer and Henry created audio portraits for the end of the machine age and the beginning of the electronic age that burst with mechanical noises, orchestral hits, trains, and text-sound babble. Doors open and close on indecipherable conversations; engines start, stop and transform into screams and moans; disembodied pianists jam with mouth noise rhythm sections. Now, almost 40 years later, the scratches on the records they used give this vanguard work a charming, antique quality.

Their studios in the '50s and '60s were hotspots of experimentation. They formed the ORTF (French Radio) Experimental Studio in the '50s, and in 1960 Henry founded the studio APSOME and Schaeffer founded the Groupe De Recherches Musicales. Among his many students was French synthesist Jean-Michel Jarre, who regards Schaeffer as a mentor. "He was very important in my life," claims Jarre, "because he was the first man to consider music in terms of sound and not notes, harmonies, and chords."

Schaeffer despised the trends of classical music in the 20th Century, still embroiled in the 12-tone and serialist methods of Arnold Schoenberg and his disciples. "This made for a century," exclaims Schaeffer, "of the most boring music. Schoenberg, a teacher lacking genius, had a 'brilliant' idea. One was supposed to use all 12 notes without repeating any. One is sure in this way to avoid the problems of tonality and to avoid copying Mahler's music.

"Unfortunately," he continues, "when you suppress the intervals between notes you suppress music. You make it insignificant. You take the feeling, the intelligence, and meaning away."

It was Schaeffer who first developed the ideas of musique concrète. Though he was born into a musical family in 1910, his parents forbade him to study music. Instead he went to the Ecole Polytechnic (the French equivalent of MIT), and studied electronics, eventually winding up as an engineer on French radio. During World War II, he was an operator for the French Resistance Radio Network.

Schaeffer's method of returning meaning and emotion to music was to go into the world and the sound effects library of his radio studio. "I was actually concerned with the possibilities of radio art," he recalls. In the process, he became more interested in his sound effects for radio plays rather than the dramas themselves. "From the moment you accumulate sounds and noises, deprived of their dramatic connotations, you cannot help but make music," he insists.

Using disk lathes, Schaeffer went to locales like the Batignolle Railway Station and etched the rumble of trains into the record's grooves. "I was attracted to external events and impressive machines," he states with a grand sweep of his cigarette. "It was an emotional experience because the railroad carries many memories, many psychological and psychosomatic feelings. Sometimes these feelings can be very violent, deeply rooted in your childhood."

Unlike the earlier Futurist work of Russolo, Schaeffer wanted to remove the original meanings and definitions of his sounds and create a deeper psychological-emotional response. In works such as Etude aux Chemins de Fer (Etude on Railroads), Etude Pathetique (Etude on Pathos), and Etude aux Objets (Etude on Objects), the sounds were familiar, but rearranged into bizarre juxtapositions, in the surrealist style of the era. The techniques of speeding up, slowing down, reversing, editing, and looping were all used to create sonic "collages," as Schaeffer calls them, all before the advent of tape recorders, let alone digital samplers.

After recording their sounds, they went back into the studio and isolated them, re-recording them onto other disks with different manipulations, including what they called "the locked groove:" putting an intentional skip in the record so a sound would be repeated, not unlike a tape loop or sequencer. Schaeffer describes the recording process. "We would have seven or eight turntables playing together, but with only one sound playing on each. Then we would try different variations, montages with let's say, sound 'A' repeated twice, then a sound 'B' then 'C' repeated and so on. It was similar to an orchestra rehearsal where you would be trying different themes, different variations."

Schaeffer has the air of a French aristocrat, dabbling with sound as a philosophical exercise. Pierre Henry, on the other hand, is a classically trained musician and composer who diverged from the traditional route to join in Schaeffer's experiments in 1949. Henry is restrained and self-absorbed, convinced that he is on the only true musical path. Henry and Schaeffer's relationship has been turbulent. They are reputed to have broken up in a violent fight in the '60s, only resuming their friendship a few years ago. Now Schaeffer, who has since stopped composing, gives much of the credit for their music to Henry. Henry, on the other hand, sat silently during Schaeffer's interview and demanded his own session.

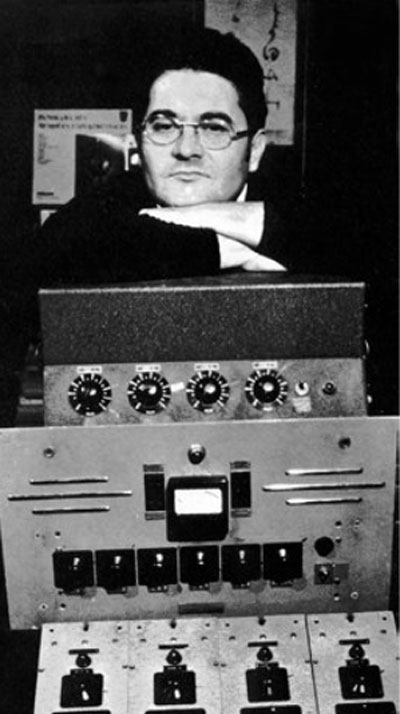

Pierre Henry

By 1951, they had tape recorders, a medium in which Henry still works almost exclusively. His studio contains a mixing console, two 8-tracks, several 2-track Studers, and rooms full of reel-to-reel tapes of raw sounds. He now calls his work "electro-acoustic music." Both he and Schaeffer are disdainful of the electronic music that in many ways they helped spawn. "It is important to understand that there is no use of electronically generated sounds in our music," says Schaeffer. "It is concerned with the acoustics of recorded natural sounds on which we then have the power of transformation."

These statements aren't entirely true, however. Synthesizers appear on Schaeffer's 1978 Etude aux Sons Animes (Etude on Animated Sounds) and sitting unobtrusively next to Henry's mixing console is an analog synthesizer. "It is just a decoration," he says with a conspiratorial grin to his aide and translator. "It is not wired in. I do not use it, but it could happen."

Henry can appear like an "electro-acoustic" snob, but he has also been willing to place his work in a more pop context. In 1969, he added electronic scribbles to the British hard rock of Spooky Tooth's Ceremony, and in 1967 collaborated with French rocker Michel Colombier on Mass For Today. Most recently, he worked with French avant-gardist Gilbert (Lard Free, Urban Sax) Artman.

Yet he considers himself part of the traditional classical music stream. He studied at the Conservatoire National Superieur de Musique in Paris, and with Nadia Boulanger and Olivier Messiaen. "I am still a traditional composer," he insists. "It is not the recording of the sound that made me different."

Henry tends towards manipulations of musical instruments rather than natural sound. "In the Symphonie Pour Un Homme Seul all the instrumental parts, piano, percussion, were played by myself," he boasts. "It was a music that I played and then, only afterwards was this music fragmented, elaborated upon, using the techniques of the time. I was also experimenting at the time with objects, noises, anything you could create inside the studio, noise from composed objects, invented objects."

Their compositions sought a musical language that fell between natural sounds and instrumental ones. They wanted the sounds to stand apart from their original context, yet have the musical values and complexity of instruments. So a door wasn't a door, but a scraping wipe across a bleak landscape. A violin no longer played scales, but a descending drone into a personal hell.

"Music has to do with sounds," explains Schaeffer, "so we need to find them somewhere and it is preferred to find musical ones. You have two sources for sounds: noises, which always tell you something-a door cracking, a dog barking, the thunder, the storm; and then you have instruments. An instrument tells you, la-la-la-la (sings a scale). Music has to find a passage between noises and instruments. It has to escape. It has to find a compromise and an evasion at the same time; something that would not be dramatic because that has no interest to us, but something that would be more interesting than sounds like Do-Re-Mi-Fa..."

Works like his Masquerage (1952) and Henry's Well-Tempered Microphone (1951) were far removed from conventional musical scales or language. In the latter work, Henry prepared a piano a la Cage and used different miking placements to generate a discordant orchestra. Remember that this was the early 1950s, and even the microphone was still a recent and relatively unexplored development.

"In the Well-Tempered Microphone," relates Henry, 'the idea was to show all the resources of the microphone and of the instrument. By using the microphone for your recording, you could go further than with the instrument itself. The microphone could amplify and magnify the effect of the instrument and, if combined with other little acoustical transformations possible at that time, it could make this effect more magic." Some of these performances would fit nicely into Looney Toons cartoons. The piano works in particular, like Concerto Des Ambiguites, have the effect of Cecil Taylor on helium. At their best, they succeeded in removing expectations and preconceptions from music, allowing newer thoughts and feelings to prevail.

Schaeffer seized upon a fire engine squealing past his Paris apartment to illustrate their philosophy. "Let us use the example of the fire engine," he exclaimed. 'What we are hearing is a musical third, a woodwind instrument, which is here a horn, and finally the siren itself. What the locked groove allows you to do is to conceal the fact that it is a fire truck, to forget that it is a musical third and it allows you to make the instrument sound like another instrument."

Although Henry worked sparingly with electronics on early compositions like Haut Voltage (1955), his best work bends acoustic material into seemingly synthesized designs. Le Voyage (1961-62) is a timbrally rich and varied excursion based on the Tibetan Book of the Dead, with only violins and voice as its principal sound sources. "There was absolutely no electronically generated sound on Le Voyage," Henry insisted indignantly. "Le Voyage was a continuation of the experiments of the '60s, but it was done in a new studio. I think that people should consider me as a creator of music and sounds who worked in different studios that he personally designed. So if there is a difference between Le Voyage and Haut Voltage for instance, it was mostly due to the studio where I was working. The sound depends on the studio where you work."

Pierre Henry at work

The sound also depends upon the stage where you present the work. While Schaeffer's and Henry's first compositions were designed for radio concerts, their music caught the fancy of many choreographers and playwrights, chief among them, Maurice Bejart, with whom Henry has had a continuous relationship since the '50s. Their collaborations, including Haut Voltage, Le Voyage, Mass For Today, and Variations for a Door and a Sigh, brought Henry's music onto the concert stage where he would sit among his mixers, filters, and tape recorders, performing live mixes and manipulations of his tapes, not unlike Stockhausen working his potentiometers or Brian Eno, who processed Phil Manzanera's guitar solos with Roxy Music.

In the '70s, Henry staged expansive works for the concert hall like The Second Symphony, which was "composed for a circular space, the Cirque d'Hiver," Henry explains. "It was a work for a 16-track recording, which was very ambitious for the time; we used eight stereo tape recorders, wired together and about 100 loudspeakers that would diffuse the sound circularly. People would feel immersed and surrounded by the music." It makes you wish quadraphonic sound had caught on.

In a more recent work, Futuriste (1980), Henry channels his sound through a variety of acoustic spaces placed on the stage. He had room-sized boxes filled with speakers, bathtubs, old tanks, basins and pipes, all lending their own peculiar resonance to Henry's prerecorded scores. "It was a work of acoustic and electric diffusion," he proudly proclaims. "For me it was the best definition of an electro-acoustic concert. It was at the same time vibrant, live, and on tape."

Curiously, some regard these vanguard artists as anachronistic in the context of new music in general, and the French avant-garde in particular. Composers associated with Pierre Boulez's Institut de Recherche et Coordination Acoustique/Musique (IRCAM) in Paris, are reputed to snipe at Henry and Schaeffer like they were doddering old tinkerers. For their part, Henry and Schaeffer take any opportunity to lampoon the high-tech computer music of IRCAM.

Schaeffer relates a Pierre Boulez story from the 1950s, illuminating the schism in French music circles. "One day we had the visit of a young and unknown musician, Pierre Boulez. At the time, I was involved in trying to create a solfege that could include many sounds and timbres. I thought we should classify the sounds in terms of their effect on the listener, of their psychological effect. We would classify them in high, low, hard, harsh sounds. Boulez objected to that. He refused to collaborate and left after composing one piece, as boring as usual, with one single sound (Etudes, 1952)."

Pierre Schaeffer with magnetic tape

Of course, with the sophisticated computers at IRCAM, like the 4X Real Time Digital Computer, Boulez and his disciples are able to work at a subtler, almost sub-atomic level of musical sound and structure than Henry and Schaeffer ever could.

Schaeffer, who has spent the last ten years composing philosophical treatises on the state of the world, relates to high technology the way people probably related to his own work when he began in 1948. "I am convinced that synthetic music, so fashionable today, is making a mistake feeding the ear with synthetic sounds. We need to come back to that."

Schaeffer may get his wish with the abundance of digital samplers on the market, taking sounds from the acoustic world with their harmonically richer structures, and manipulating them into new shapes. Yet, when queried about it, neither Schaeffer nor Henry seemed very interested in the new technology. But embracement of new technology isn't really the point. Technique ultimately is not music. Henry's methods may be archaic by contemporary standards, but the resulting music is powerfully evocative by any standards. Popular artist Bill Nelson records his personal music this way, claiming it has an intrinsic and emotional value not unlike woodcarving. He's joined in this opinion by Brian Eno and Holger Czukay.

Pierre Schaeffer and Pierre Henry made a contribution that has helped shape music for the last 38 years, be it the early tape music works of Otto Luening and Vladimir Ussachevsky at Columbia, and Stockhausen in Germany, the Beatles in their Sgt. Pepper days, or producers Arthur Baker and Martin Rushent today. They owe their genesis to the sounds of a world rearranged by Pierre Schaeffer and Pierre Henry.

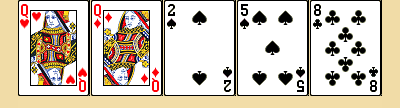

Poker hands have the following rank, from strongest to weakest:

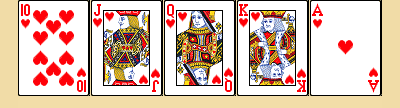

Royal Flush: Suited sequential cards Ten to Ace.

Example:

Straight Flush: Any five sequential suited cards.

Example:

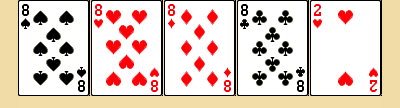

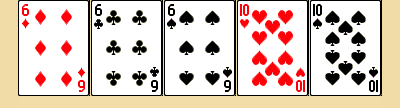

Four of a Kind: Any four cards of the same rank.

Example:

Full House: Three cards of one rank, two of another.

Example:

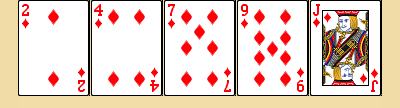

Flush: Any five non-sequential cards of the same suit.

Example:

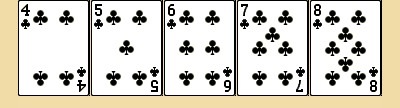

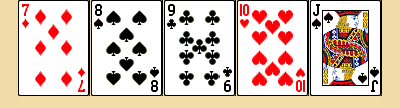

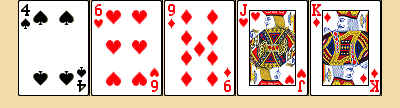

Straight: Any five cards in order, unsuited.

Example:

Three of a Kind: Any three cards of the same rank.

Example:

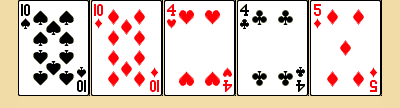

Two Pair: Two pairs, each having cards of the same rank.

Example:

Pair: Two cards of the same rank.

Example:

High Card: The hand's strength is measured by the rank of its highest card. Ace is highest, 2 the lowest.

Example: (King high)

There are several things to be aware of when looking at the relative strength of a hand. First, if two or more players have the same kind of hand at the end (such as a flush), the winner is the one with the highest-ranked card (which must be involved in his hand).

For instance, if the board looks like this: 4h-7h-9d-2c-Jh, and Eddie is holding Kh-3H, and Mike is holding Th-5h, then both players have flushes. However, Eddie wins because he has a “king high,” while Mike only has a "ten high."

If two players both have three of a kind, the winner is obvious--it's whoever has the higher-ranked trio. Three sixes beats three twos. The same goes for four of a kind. When it comes to two pairs, the winner is the one with the highest-ranked pair. Pairs of kings and threes beats jacks and tens.

If players have the same high pair, then the decision goes to the highest secondary pair--if they happen to be the same, the winner is then decided by the kicker. The kicker is the unpaired card. Whichever is higher, wins.

The same holds true when two players have the same pair. Whoever holds the higher kicker wins. For instance: if the flop is 3d-5h-Th-Qd-Ks, and Eddie holds K4 and Mike holds KJ, Mike wins with his jack kicker. (On the other hand, if Eddie had K4 and Mike held K2, the two players would tie, and split the pot. Can you see why? Their kickers don't beat those of the “board”--Q-T-5, in this case--so the extra card each of them holds doesn't come into play, is not included in their best hand.)

In April of 1989, an unidentified music critic tried to get Rod Miles to perform an unnatural and illegal act in the restroom of one of our local Austin clubs. Even though we desperately craved all the publicity we could get, Rod refused to stoop to this level. (Actually, we would probably be famous today if not for a severely strained back muscle that would not allow Rod to stoop back in April of 1989.) Anyway, if said critic would give Rod a second chance, Bentley and I believe we have convinced Rod to do what it takes to get ahead in this vicious musical business.

YU is C.U. Squirm, Rod Miles and Bentley Shaft. Three real men doing what real men do. Don't call them - they'll call you. Seriously... they'll call you.