Facsimile Magazine, Published by Haoyan of America. Volume Three, Number Twelve, 2009. ISSN 1937-2116.

Facsimile December 2009 ~ Music Within Memory

Contents

Facsimile Magazine, Published by Haoyan of America. Volume Three, Number Twelve, 2009. ISSN 1937-2116.

Contents

Festival Review & Photography by Andrew Choate

Part 1 of this article may be read at Facsimile November

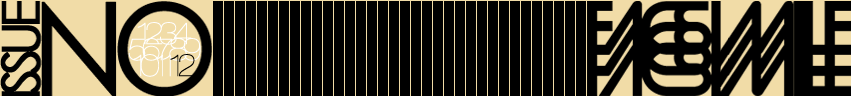

In addition to the concerts of the Ostrava Days festival, two galleries featured related exhibits. The scores by Czech artist Pavel Rudolf in Galerie Beseda ranged from semi-traditional to pure graphics. In the example pictured above, staffs are filled with notes and nothing is too out-of-the-ordinary. Except for the huge swooping arcs that connect, or possibly redirect, notes in one place to another moment in time. And yet it's also possible to read the lovely curvature of these arcs as representations of the sounds in the air, not as instructions for their actualization. The image captures both the guide and the expression simultaneously.

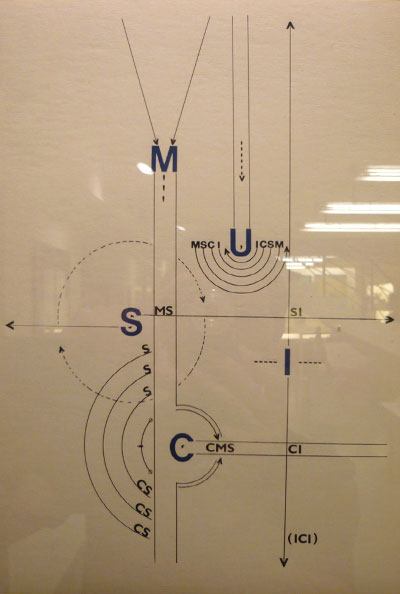

Other scores took more liberties with the form, replacing the implied arrow of time that is the staff with actual arrows that curve and break and focus attention on forms in space whose musical meanings are less obvious or overt. Breaking down the letters that form the word "music" may seem like just a simple, if clever, bit of circularity - especially considering the circles involved - but when I look at this score, I literally hear gorgeous sonorities. In fact, as Rudolf's scores got more and more abstracted from traditional notation, I started seeing and hearing music that I wanted to bring to life. I'm sure my confidence in this endeavor was due to the immersive nature of the Ostrava Days experience, but isn't that kind of excitement-of-the-imagination what any arts festival should be striving for?

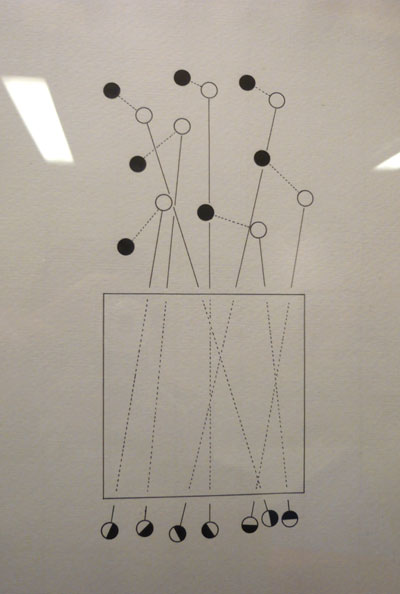

From the first moment I saw this score, I immediately began taking notes on how to realize the music that I heard emanating from it. I figured that, if a conductor's job is to imagine what s/he wants to hear out of a score and bring it to life, then I owe that vitality to this score. (I'm currently working on the arrangement with musicians in Los Angeles.) Throughout the rest of the fest, these scores by Rudolf pleasantly haunted me.

The other exhibit was a sound installation at Fiducia Galeria by New York composer Michael Schumacher. Ten speakers and a couple of chairs were scattered inside a dark room behind closed doors above a used book store. The sonics were similar to the recordings of earth's magnetosphere that Stephen P. McGreevey has done such an excellent job of documenting: whistlers, tweeks, etc. Schumacher augmented these timbres with rare piano strikes, watery propeller spirals and crickety blips. It felt less like an installation than a composition that you can walk around and sit in.

I spent forty-five thoroughly agreeable minutes inside it and, before I left, apropos of I know not what, wrote "sentient folly: I've got a line of credit that would make a gymnast sweatless" in my notebook.

In the evening the Ostravská Banda took the Philharmonic stage for their second performance. The world premiere of Joseph Kudirka's "Renascence" (2009), a student piece for voice and unspecified instrumental accompaniment was the highlight of this set. Edna St. Vincent Millay's 200+ line poem was the center of this work, with Thomas Buckner's baritone giving it a full workout. The instrumentation also included trombone, piano, violin and percussion, and I loved the fluid way the instrumentalists chose to accentuate various moments in the recitation: scratching bongos, squeaking strings, pouncing piano, etc. Millay's rhyming poem has a force and rhythm of its own, but Kudirka and Buckner channelled that energy into a solemn, ebbing, dreamlike reverie based on the sonorous expectations that rhyme induces. The pinch was acute.

After a break for dinner, the Janáček Philharmonic was once again onstage for some large orchestral pieces. Uh oh, first on the program was Elliot Sharp's "On Corlear's Hook" (2005). I don't know how you compose something for so many people to put so much time into that has such little grandeur - just short-lived, flicked bombast. I also can't figure out how such a mediocre composer gets such a great invitation to present work: his resume is a bunch of typically middling releases from the typically middling Tzadik label. Seems like his reputation has been built on being at the right place (NYC) at the right time (late 70s, early 80s) to be mistaken for an innovator. That's probably because no one else living and playing in NYC, then or now, seems to have (had) a grasp of what's going on in the world of improvisation-meets-other-genres outside of NYC. Don't get me wrong, there's plenty of decently acceptable stuff that's come out of the NY area, and I think the Golden Palominos' first record is a completely unique, could-have-only-happened-in-NYC kind of bad-ass, can-never-be-loud-enough, genre-wrecking triumph. But Sharp ain't on that record, that whole scene has never done anything to match it in 30 years, and most of what I've heard supposedly coming out of the avant-garde elements of the city over the last twenty years is tired and marginal-at-best compared to Chicago, Colatown, London, Vienna, Berlin, Amsterdam, Tokyo, Osaka or Melbourne.

I've got a lot more to rant about how crappy, insular and overrated I think New York underground/ creative music is, but I'll stop here for now. And it's not that I'm a Californian nursing a grudge - I think LA is destitute in many, possibly more, respects - it's just that I'm disgusted over what passes for creativity when it's stamped "from New York." I'm from South Carolina, where musicians are expected to digest Anthony Braxton, Kain, Captain Beefheart and Carl Stalling by the time they're 17, and then start composing and performing.

Peter Rundel has the hair of a great conductor. He conducted this Sharp piece that got me all riled up, and I couldn't help but spend time wondering what he listens to when relaxing and trying to get away from his work - Booker T and the MGs? Mal Waldron? Giles, Giles and Fripp? I don't know, but I hope so.

František Chaloupka, a former student of Ostrava Days, then had his "Naklonit si Nebesa" (Smooth the Heaven) orchestral piece from 2009 conducted by Petr Kotík. This composition presented the orchestra in wonderful balance, with a second section pounding out powerful blasts of extreme pitches and the strings seemingly tearing a hole in time, so frantically were they bowing. The punctuality of the finishing flute was perfectly coordinated with the rhythmic and color spectrum displayed.

Viennese composer Bernhard Lang's "Monadologie II: Der Neue Don Quichotte" (2005), conducted by Peter Rundel, explored the concept of looping in an orchestral environment. It's a strange thing to hear an orchestra effectively "scratched," like a record on a DJ's turntable, producing spiraling reiterations and jumps. The composition was inspired by the films of Martin Arnold as well as philosophical concepts from Leibniz and Deleuze in combination with how the mediums of technology effect our experience of culture. While charged with carrying a lot of conceptual baggage, the music itself was inviting, if twisted, and left me fascinated.

The concerts on the seventh day took place amid the bright, stone acoustics of the St. Wenceslas Church. The predominantly vocal-centered lineup was very well-served by the sound here. "Recitation, code, and (perhaps) round," a 2009 student composition by Michael Winter, dispersed several vocalists around the audience, along with small percussion.

The text of this piece was a poem by Elizabeth Winder, "Now Trips a Lady, Now Struts a Lord," and I was completely engaged from the first line: "Lost my cat."

The piece progresses with many repetitions of the short poem, and I loved hearing the familiar words stretched to the point of linguistic unintelligibility while the harmonic mass became denser and more complex.

The origin of the piece encapsulates another facet of what makes this festival so unique. Festival director Petr Kotík requested a choral piece from Winter, knowing that he had never written one before. Ostrava Days supports composers by pushing them to try new things, thereby establishing an important basis of confidence through encouragement. The value of this kind of artist-to-artist mentoring outside of a university setting cannot be overestimated, especially considering the rampant denigration of intellectual activity that defines modern life. The enthusiasm of the teachers and professionals also rubs off on the students, who get excited about each other's work: if they feel that an intermission is going on too long, they hurry back to their seats so they don't miss a comrade's piece. A keen community atmosphere.

Mezzo soprano Katalin Károlyi then sang Berio's "Sequenza III" (1966), and she gave everything that this extraordinary piece requires. As a solo vocal piece, it is serious and silly and dramatic and soft and nerve-wracking and sensuous and horrific and playful. Károlyi has a wonderfully theatric sensibility to begin with; using the full range of her vocal skills, she developed a perspective on each note she sang. It was such a treat to hear this piece performed so honestly that the entire audience seemed to relish and cherish every moment, absolutely erupting in applause when it was over. Károlyi modestly held up the score, lifted her eyebrows in its direction and gave a big, twinkling smile of knowing thanks to both audience and score.

Hamburg-based double-bassist John Eckhardt was one of many individual performers and soloists the festival brings in to augment the orchestra and ensembles that will be realizing various compositions. As an enthusiast and critic of improvised music, I was familiar and impressed with his CD Xylobiont on PSI, and had been enjoying his chamber playing throughout the fest. For this solo, he played a ten-minute improv: it was good, not great. He stuck stuff in the strings, he bowed under the bridge, he played the side of the bass - a lot of typical extended double-bass techniques. It wasn't bad, but it started to feel a little tedious, as if he knew he had a certain allotment of time and was trying to fill it without pausing rather than investigate a series of sounds to an unknown conclusion. To my mild surprise, several student composers I talked with were completely smitten with his performance. I chalk it up to the fact that they've never seen or heard Barry Guy, John Edwards, Wilbert de Joode, Joëlle Léandre, Peter Kowald, Barre Phillips or William Parker.

Student Nomi Epstein's "Solo for Large Ensemble" (2009) was the only piece that did not benefit from the particular acoustics of this church. No voices, lots of instruments close together - all I heard was nebulous frothing. A tempestuous crescendo emerged out of the rumbling, but I couldn't tell if it was a moment of compositional clarity or simply better acoustical reverberation due to the instruments stopping.

Vitkovice - it's still there.

Irishman Donal Sarsfield's arrangement of Gerard Manley Hopkins' poem "Repeat that, repeat" (2009), for large choir, possessed a perfect combination of playfulness and investigative intelligence into the choir as a medium. As the Canticum Ostrava choir stood in a semi-circle, each word bounced around the singers in an exploration of spatiality, repetition and the tension between unison vs. a cappella singing. A perfect coalescence of compositional form, venue and performance.

Choir master Yurii Galatenko then led the Canticum Ostrava through Xenakis' surprisingly sweet "A Hélène" (1977). I could barely contain my anticipation for the next piece: Gérard Grisey's "Anubis/ Nout" (1983) for contrabass clarinet. For one thing, clarinets are my favorite family of instruments - I just love how round and deep their resonance is - but I have an even greater affinity for the really big, low clarinets. Add to that the fact that I was still glowing from my introduction to Grisey's music a couple days earlier when the Quasars Ensemble played his "Vortex Temporum," and you can imagine how eager I was for this piece. Theo Nabicht, whom I was familiar with from his discs with the Clarinet Trio on Leo Records, gave an outstanding performance of Grisey's composition, with tons of growled multiphonics and lustrous, hazy mewings. All I could do was listen and absorb. And be absorbed.

Chikage Imai's "Vectorial Projection II - turning of the lathe" (2007), a duo for contrabass clarinet and accordion, was an unexpected treasure in the program. I never would have thought that an accordion, played brilliantly by Milan Osadský, and a contrabass clarinet could blend so well together. An astonishing piece that just happened to be written by a student. Everyone I talked with about this piece felt newly awakened, as if freshly invigorated to start thinking and reevaluating ideas and preconceptions about what instruments supposedly "go" with others. "Light blue", a 2007 piece for piano and choir by student Hiroki Tsurumoto, was another composition that my body found very nice to listen to. Pretty, but not cloying; smart, but not bogged down in hyper-conceptualization: just fine music.

Hands together for the decision to program these performances in the church: with so many concerts over so many days, having a variety of venues helps keep the ears attuned to the finer nuances of any given environment. Alas, this program ended with another Elliot Sharp piece, "OVOXXOVO" (2009). Actually, this one was likable enough, using the choir to deliver long tones and no letter sounds. As an aesthete, supporter of the arts, and huge believer in the non-quantifiable value of them, I don't enjoy the firing of blistering critiques at any artist. Especially considering that at a festival like Ostrava Days, a community is formed, and ostracizing someone or their work is uncomfortable. But the music isn't served by an inability to evaluate or appreciate distinctions of quality. And it's the blandness of countless contemporary works like Sharp's that make it that much harder for the truly unique ones to find their place: people get too busy wading through the muck. Even the way Sharp describes this piece once again calls into question the intellectual rigor of his compositional methods. He writes: "The sung palindromic title has been recorded and time-stretched. The resultant soundfile was transcribed and orchestrated for choir." A nice, simple idea to explore a nonsensical-though-vocal-inflected palindrome is cluttered by the introduction of technology, where all that the technology offers is the introduction of technology. I had a nice fish afterwards, to clean and recalibrate my scales.

As a break from the formality of all the chamber music, the rest of the night's concerts were in a bar, Club Parník. This was a great atmosphere to just hang out and talk. A "retro-pop" guitar-bass-drums band, Koistinen, was on the stage when I showed up, and the first thing I noticed was how pleasant it was to hear decent amplified music with a backbeat. That, and how delicious the local pilsener, Ostravar, is: it's creamy and smooth with just the right mineral bite. And with specially designed troughs, ten liters can be carried at one time.

Faces hidden to protect the innocent.

An improvised solo on shepherd's pipe from Zdeněk Berger got me properly swirling, but it was Bosnian šargija player Ivica Lovrenčec who stole the show. The šargija is a six-stringed Balkan folk instrument that Lovrenčec strummed fast while singing long, drawn-out lines that sounded like "veeeeee-vuh kotchee-kotchee rah-noh." While he was playing I couldn't help but start swinging my head and smiling: my body had to react. Considering all the wonderful music I had heard over the last several days, it was shocking for me to realize that, up until this moment, I hadn't been able to express, with my body, that I was enjoying what I was hearing. There was a desperate yet jubilant intensity to this performance, and the concentrated force of his vocal delivery still haunts me, in the best of ways.

Three students then played a viola, accordion, alto sax improv. At one moment, the alto saxophonist Lucie Páchová leaned back and rested her body against the piano behind her and began puling deep vocal sounds out of her insides. It was one of those great moments that happen in improv, where the music demanded something that the performer couldn't have anticipated, and she responded by giving herself completely up to the moment and the music's demands. It was like she needed the ballast of the piano to hold her up so that she could concentrate on digging down into herself to find the necessary sounds. She embraced her own vulnerability, and in the process found the strength to express the music that wanted to come out. From relaxation to revelation.

One thing I've learned from attending a lot of festivals devoted to intensely adventurous music is that, at some point, you always need a dance party.

Thankfully, John Eckhardt, as Funksteppa, obliged. He records beats and bass sounds, plays 'em back, and then plays live electric slap-funk bass on top. Composers, performers, students - all of us needed the opportunity to shake our asses a bit. The only complaint was that it stopped before dawn.

Some of Amadinda's instruments (Rotate head 90 degrees right)

When I walked into the hall before the performance by Budapest's Amadinda Percussion Group, I was surrounded by percussion instruments. It was like standing in the photograph from Roscoe Mitchell's "The Maze" record. Times five, and with less xylophones and more one-of-a-kind instruments: oil drums, carved Polynesian log drums, carpets hanging perpendicular to the floor, beerkeg marimbas - a seemingly infinite array of cymbals and percussive objects. Besides being visually overwhelming, the program for their concert looked gleefully ambitious: a first set of two original compositions, a second set of avant-garde percussion classics by Cage (Imaginary Landscape Nos. 2 and 3; Third Construction) and Ligeti (Síppal, dobbel, nádihegedűvel), and then a third set playing a 72 minute John Cage percussion piece written explicitly for this ensemble. The first piece they played set the tone for the night. Aurél Holló and Zoltán Váczi's "Traditions - Part One/ The Winning Number - beFORe JOHN7" is one piece within a series they've written to connect traditional percussion cultures to prominent twentieth-century movements in music. The members of the quartet played instruments arranged on a mobile metal stand while they spun whistling, whirring tubes overhead and broke out into staccato vocalic bursts. Delicate chopsticks on decelerating bicycle-spoke spins marked tempo variations within the piece. The composition specifies that the performers should be as close to one another as possible while they play, in order for them to share each other's instruments - a common practice in traditional percussion music made visually alive when they ended the piece by rolling the stand offstage while whistling and still banging away, creating a slow fadeout.

Check this instrument out.

This little gong summed up a lot about this band. It's a small plastic bathtub on wheels with a gong hanging above. It was struck with a mallet, then, using the soft felt pad connected via bungee cords, was slowly lowered with knee pressure into the tub. The sound shimmers when above the water, reverberates deeply against the walls of the tub as it descends inside and mutes when it touches the water. Not only is the sound fantastic, but the design serves a very specific purpose: when it is played, the performer is holding and playing other objects in his hands and doesn't have the freedom to lower the gong in any other way other than with his knee. The care that went into developing this instrument is the care that they displayed for every note they struck. (Note the witchy broom adjacent.)

During the early Cage pieces that started the second set - how can you not love a turntable and conch duo? -, I was becoming more and more overcome with delight at finding myself listening to this music. At one moment of complete rapture, I wondered why anyone would write anything besides percussion music. After the great Cage pieces, Amadinda, joined by Katalin Károlyi, regaled the audience with Ligeti's "Síppal, dobbel, nádihegedűvel" (2000). (This is the formation that recorded this piece for the Ligeti Project CDs on Sony/ Teldec, and for whom the piece was written.) I love vocals, especially vocals that play with the physical properties of speech, so this kind of composition is right up my alley. It's got drum blasts, moody changes and soft silences around dispersed rhythms. The theatricality was lost on none of the performers. What I remember most distinctly about this performance are the long pauses between percussive strikes, and how impressed I was at how perfectly-timed the percussionists all were when it was their time to simultaneously hit something. No metronomes, no click-tracks: just living so intimately with the spaces around the beat to know, practically instinctively, when to strike. We expect percussionists to have an outstanding feel for time, but this was something beyond that: more than a performance, it felt like a complete embodiment of the composition.

The members of Amadinda.

In fact, a conductor (who shall remain nameless) confessed to me that only twice in his life has he found himself in the midst of conducting to be following what a performer is playing: once was when conducting a piece with Amadinda in the orchestra. He didn't even realize he was doing it until he was. That is how infectious Amadinda's sense of timing is.

Károlyi's role in the Ligeti piece was equally as important: she projected a real sense of dedication and respect to this music, and also a thoughtful appreciation for the wildness that is at its heart. She controlled and concentrated the primal vitality at the center of this composition so it could come out in viscerally compelling vocalics.

Can you grab me a boogie?

After two sets of Amadinda's music, I started to feel not only personally reinvigorated, but suddenly optimistic for the planet. That's rare for me.

If music like this can be written, performed and appreciated, then humanity does have some redeeming characteristics after all. While the festival as a whole provided that sense for me, it was Amadinda in particular that planted that feeling directly inside.

The author with Hana Kotková, in-between sets by Amadinda

Amadinda's final set began with a heartfelt dedication to the recently passed Merce Cunningham and a brief description by Zoltán Rácz of the week he spent staying with Cage and Cunningham in 1991, a time during which Cage wrote "Four4" for this quartet. All of the hundreds of instruments that had been filling the stage were now cleared away, and the hall was completely dark except for four firefly-size lights, one for each percussionist. It looked so beautiful and careful that I didn't even try to take a photograph: I knew I'd have no problem remembering this image. Before the set even began, the members of Amadinda took great care positioning themselves for the long composition ahead, Rácz gently lifting and placing a chair in such a way that the sound it made would not be unpleasant or obtrusive to the anticipatory quiet. The care they were displaying for the qualities of the sounds that would simply frame this performance transformed the audience as well: people became silent and still. The ambience couldn't have been more relaxed or suspenseful: late at night, sitting in the dark, waiting to listen Cage's music.

This was Cage's final percussion composition, and while it doesn't specify which instruments to use, it does require two of the performers to choose five instruments, and two to choose four; obviously, with such a vast assortment to select from, the instruments chosen were incredibly sophisticated and unique. Holló had hung some pitched wooden chimes, which he caressed from the bottom, like he was scratching a good dog's chin, and an enormous, carved, black Tibetan singing bowl that had such profound resonance that the entire hall seemed to bend in undulation with its waves of overtones. Károly Bojtos played one of the strangest things I've ever seen: it looked like an aluminum cylinder/ resonator with rubbery tentacles hanging from it. When he played it, I thought I was watching a jellyfish burlesque. Its reverberations were equally otherworldly: wet, twangy, bright and stretchy. The composition itself has so much room for silence that the actions of the audience are intimately involved with the experience of any live performance of it. At one moment, Bojtos was creating a spiraling tunnel of squiggles by shaking and playing the squidlike thing, and these peculiar vibrations opened up a wormhole of gastrointestinal bubbling inside some folks around me. The sounds the stomach makes when it's hungry have always fascinated me anyway, but they took on a whole different dimension of acoustic significance when juxtaposed with the bizarre bouncing burbles coming from the stage.

As one of Cage's later "Number" pieces, "Four4" doesn't specify what should be played at any specific moment; rather, it tells the performers when to play, and for how long. There are times when the brackets indicating that a performer should play will overlap with times that other performers are playing, and there are large stretches of time that indicate that no one should be playing. The piece thus has a very tranquil flow that encourages a state of more and more increased receptivity to all the sounds in the auditory landscape. As an audience member, It is mildly hypnotic to be so aware of your surroundings and yet remain so motionless within them.

I don't know how, but I had sort of forgotten how much good listening there is to be had in Cage's music. While everyone involved in contemporary music appreciates Cage and his contributions to some extent, after you discover him, research him and move on to other composers, his ubiquitous presence can make him easy to take for granted. But this rare opportunity to experience a performance of this piece reminded me how genuinely pleasurable the sounds produced by his music are. A pause after a slowly rubbed drum skin by Bojtos opened up the space to hear the ceiling in the Janáček Philharmonic Hall creak; when I looked up, it appeared as if the sound emanated from the spot directly above where the drum's skin was pointing, one hundred and twenty-five feet away.

Every instrument Amadinda chose for this set had an incredibly distinctive timbre, and I've already mentioned the waves created by the Tibetan singing bowl, but in combination with the gongs played by Bojtos and Zoltán Váczi, there was just no escaping a complete envelopment in the swells of humming harmonics that lapped at the ears and made my bones vibrate. This transcendent set left me so completely ensorcelled that an usher had to tap me on the shoulder thirty minutes after it ended in order to rouse me from my focussed captivation.

Silver apples are everywhere. (Rotate head 90 degrees right)

Even an hour after this concert, I couldn't stop reflecting on it. It seemed to represent the life-changing power of serendipity, in the sense that so many things had to align in order to make it happen: the members of Amadinda had to go to school together and meet; one member had to follow his instinct and passion and go to New York to meet Cage, Cage had to write them a composition, they needed the kind of open-minded invitation from Ostrava Days that would allow them to perform it, etc., etc. Of course, there are an additional infinity of smaller coincidences and confluences of events that led to my attending this concert, which I ruminated on while drinking Becherovka at a bar on Ostrava's infamous Stodolni street afterwards. As I was writing and watching all the passersby on this busy street, I heard a big chorus of voices coming from a nearby bar and decided I needed to check that out. I should have guessed - it was a karaoke bar! After belting my way through Deep Purple's "Black Night" (not the best choice - I don't think anyone in the place had ever heard that song before), I was flipping through the book looking for another tune when Amadinda's own Zoltán Rácz waltzed in the door. We watched an inspired Czech/ German duet sing "Angels of Harlem," drank a beer and talked. This simple coincidence made me feel that even though I've made a lot of mistakes in my life and taken plenty of wrong turns, somehow I'm doing something right if I can end up in Ostrava for this festival, hear Amadinda play, and then, hours later, end up at the same bar where Zoltán Rácz decides to grab a nightcap after his gig. Everything does not happen for a reason, but sometimes, only sometimes, things make sense. And by make I mean create sense.

It feels like I'm done reviewing this concert doesn't it? I'm not. The review lingers. While I was in the bar with Rácz, a brief rain had fallen on the city. As I was walking home around two in the morning, I realized that the temperature I was feeling was the most pleasant I had ever felt anywhere before - and I live in Southern California. I had on a T-shirt and pants; the air was light, with just the scent of a chill in the air - just enough of a chill to sense the temp with another organ while the skin was in heaven.

At lunch the next day I had the good fortune to run into Petr Kotík and his mom. After Kotík introduced us, he was interrupted by a musician with a question, and his mother turned to me, unprompted, and said: "Petr always wanted to play this kind of music." I love it: even the legends of New Music have parents who think that what they're into is slightly off-kilter. But they're also keen enough to recognize that, for some of us, we have an ingrained sense of passion that refuses to be veered off course from what we love, regardless of how marginalized it is. My mom has gotten so used to the wild music I've been playing around her for the last sixteen years that now she chooses to play Ornette Coleman and Helmut Lachenmann when company is over, thinking they make perfectly agreeable dinner party music.

The final day of the festival started with afternoon concerts at the Janáček Conservatory. Pavel Bizoň's "10 Pieces for 10 Musicians and Tea" (2008) began when a tea-kettle, placed center-stage, was turned on to boil. While six of the musicians onstage played traditional instruments, four were positioned near the back, clinking glasses, dropping chess pieces, folding newspapers, etc. The looming, volcano-like fizzing of water reaching a boil created a palpable awareness of time passing. As the pieces within this composition unfurled - the tea boils, everyone's cup is filled and sipped, musicians read and drink - the music overlapping with the ambience created a surprisingly coherent whole out of diverse conceptual elements. I don't think all ten sections were warranted, but, as a bit of theatre exploring the social and sonic life of a musician, it was very entertaining.

Ákos Zarándy's "Step by Step" (2008), for solo clarinet, was adroitly played by Daniel Svoboda. I've mentioned how much I love clarinets, so it's hard to go wrong by me with a clarinet solo, but this piece was actually more of a duet for clarinet and creaking wooden stage. I don't know how much the composer appreciated that combination, but even Svoboda's most minor movements with his feet effected the creaking; I loved the depth it added to the romantic nature of the clarinet part.

Zuzana Biščáková played piano in five compositions that were featured this afternoon, with Jonathan Herbert's "Re(-)presenT" (2008) being the first. I'm pretty clueless when it comes to fashion, but the garment she wore was absolutely and stunningly perfect for a pianist. It was a black blouse that bared her shoulders, gripped her upper arms, and hung loose from the elbow to the wrist, allowing it to wave and swoop in the air as she moved her arms to strike the keys.

The only non-student composition performed this afternoon was Christian Wolff's "For 1, 2, or 3 People" (1964), and it was performed by Wolff, Finnish cellist Juho Laitinen and baritone Thomas Buckner. Wolff has such a relaxed air about him and his music that I always find it very enjoyable when he performs his own work. This piece makes plenty of room for space and texture and freedom, which was capitalized on by these three. Laitinen was exceptionally focussed and creative, and the resonance not only of the acoustics but also of the aesthetic philosophies between these three performers turned this composition into simpatico mischief and delight, with a dynamic emphasizing interaction over notation.

During the course of the 2009 festival, Buckner led students in improvisation workshops, culminating in one performance by the eleven-person OD Improvisation Ensemble. Their improv definitely had a mild flavor of neophytitis, but they were listening carefully - which is half the battle with beginning improvisors - and the sonic interactions were better-than-decent considering how many people were onstage. Some students chose to be theatrical, considering improv an open door into more performance-art-related activity, and spent more time moving around the stage than playing music, which seemed less like an expression of freedom than an instance of all-this-freedom-is-forcing-me-to-behave-uncharacteristically-unconventional. I found the movement distracting, but other performers were undisturbed and carried on in a successful attempt to chart the topography of a new soundscape.

After the intermission, three solo compositions rolled along. I appreciated the simplicity of Mátyás Wettl's "Knock it out" (2007) for solo percussion played by Chris Nappi, though I couldn't understand how the first and section sections of Evan Antonellis' "Twelve futures" (2008), for solo piano, added up to one composition. The first section was dense and dissonant, and the second section was romantic and melodic: I couldn't tell how they were related. On viola, Etelka Nyilasi performed her own "Pastorale" (2007), incorporating bluegrass, extended techniques, Hungarian folk music, jazz and serialism into a piece that didn't quite coalesce but was entertaining nonetheless as it displayed the enthusiasms of a curious mind.

The best piece, as it turned out, was saved for last. Even after listening intently to ten previous works, K.C.M. Walker's "For You" (2008), for piano and three percussionists, immediately grabbed my attention and didn't let it go. The four musicians were listening to individual click-tracks, and began playing simple quarter-notes, starting with one percussionist playing one note in each bar, then the piano playing one note in each bar, and so on, each musician out of sync with the others. Then, in a wave, a note was added to each bar, creating a two-note sequence. Then a three note phrase, etc. The bizarre phasings in and out of the four musicians made the music both emotionally engaging and conceptually rich. This piece had a real clarity of compositional intent: it got hectic as it got denser, but that was partly the point. Then it slowed down and ended just as gracefully as it had begun. It contextualized simplicity while containing fractalized fragmentation at its core: another outstanding student work.

If your passions lead you far from the center of culture, you'll need emotional support from somewhere.

The final concerts of the festival took place later in the evening at the Philharmonic Hall, beginning with the world premiere of Christian Wolff's "Rhapsody for Three Orchestras" (2009). Spread out across the stage, three ten-person ensembles grouped around their respective conductors - Kotík, Kluttig and Rundel. Wolff is not as interested in big bleeding blends of sound, instead considering an orchestra to be a collection of individuals rather than a single organism; accordingly, this piece featured solos for almost everyone and surprising little duets across ensembles: a bassoon in one group wailed in correspondence with a lonely trombone on the other side of the hall. The sound seemed to be percolating, punctuated by bubbles of solos popping up and bouncing around the room.

Ondřej Vrabec then conducted "Rojo sobre Blanco" (2008) by student Pablo Chin Pampillo, a bold piece that plays an oboe against an ensemble of cello, violin, viola, flute and clarinet. Rapid pad-popping and barely-articulated breaths from the wind instruments played off of a sudden, piercingly-high, sustained cry from the oboe before igniting a slow sparkle of strings that fizzled and exploded like a small stick of dynamite thrown down an isolated, abandoned well.

I don't remember a single moment from Kotík's conduction of György Ligeti's "Concert for Piano and Orchestra" (1988), a sure sign that I enjoyed it voraciously. One aspect I do remember of this performance is the bracing aggression that Dutch pianist Daan Vandewalle brought to this performance, an attitude I appreciated since I think the composition is better-served by confrontation than demural.

One defining characteristic of composed music that distinguishes it from other genres like rock or jazz is that the people who perform it are generally not the people who envision it. That's obvious, I know, but the differences that this causes need to be intellectually and physically absorbed from both sides, over time, before the ramifications of this difference yield relevant understanding. One result of this disjunction is that some members of an orchestra will pay only perfunctory lip service to a piece of music they are required to play, creating a difficult-to-bridge divide that it becomes a conductor's responsibility to engineer. Despite stories of tense, fractious rehearsals, conductor Peter Rundel did an outstanding job leading the Janáček Philharmonic through the world premiere of Canadian student Cassandra Miller's "A Large House" (2009), a dense, hypnotic piece for string orchestra. This was an incredible aural experience, as hundreds of strings rocked back and forth across the large philharmonic hall for over twenty minutes. It was like a boat creaking, but somehow rocking on both sides simultaneously, sending waves through each other and creating a pulsing vortex. I absolutely loved how the duration and instrumentation of this composition unstabilized me as a listener: my ears had been so fully transported that, when the piece ended, the acoustics felt so different that my ears had to pop and readjust; the perception was as if they had undergone a change of elevation.

The final concert of the festival featured Roland Kluttig conducting the Janáček Philharmonic in Edgard Varèse's "Amériques." Rightly, the percussionists were highlighted by being placed on the stage above and behind the orchestra. A climactic, boisterous piece in its own right, "Amériques" was perfectly placed as the finale of this bold, discerning festival. At the very end, when it seemed like the hall was about to fall down out of sheer pummeled exhaustion from the heavy percussive emphasis, the orchestra still had to be pushed harder and further and louder to reach the frenzy that marks the conclusion of this composition. Kluttig clenched the conductor's baton in his fists and in one gesture appeared to be both pulling the sword from the stone and committing harakiri all at once; the orchestra responded with a supreme blast that literally shook the audience out of its seats. It was an absolutely stunning, exhilarating and fitting climax.

A park in Ostrava.

When I checked out four books from my library on the Czech Republic before I visited, I got a total of three pages of information on Ostrava, the third-largest city in the country. Considering the city's charm, culture and scenery, I expect a lot more attention will be paid to this city in the future. By embracing such a unique and visionary festival, the city of Ostrava is demonstrating that investing in cultural risk and imagination reaps rewards that far outshine and outlast typical cultural initiatives. As this is only the fifth incarnation of this festival, and it's still in the process of becoming, I look forward to seeing how it continues to expand. With a person as enthusiastic about so many kinds of music as Petr Kotík - a man who has successfully struggled to maintain the integrity of his passions -, the potential is vast.

"New Music" may have a reputation of austerity in the popular imagination, but what I heard was so glorious that I often felt myself wishing I had more ears to hear with. Because of all the music, the gallery shows, the conversations and the people who take part in Ostrava Days, this was one of the densest cultural experiences I've ever had the pleasure of participating in: my time in Ostrava was a solid block of continuous aesthetic stimulus. One thing that united the best pieces in this festival was their origin in imagination as the basis for a work of art, an understanding that imagination is our unique human gift: we are imagination-based lifeforms.

Thanks to Petr Kotík, the staff of Ostrava Days, all the artists involved and the city of Ostrava. A condensed version of this article appeared in Signal to Noise #56, Winter 2009.

By Continuo from ubuweb.com

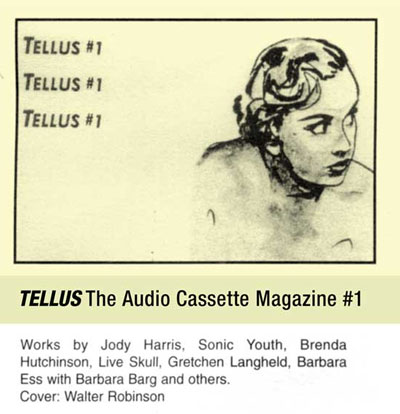

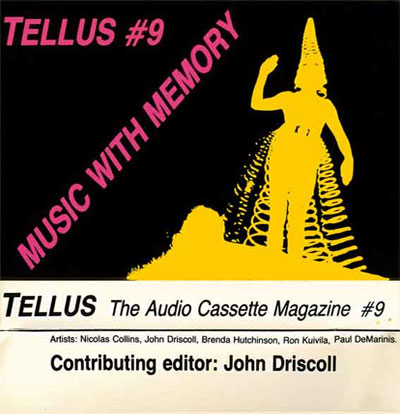

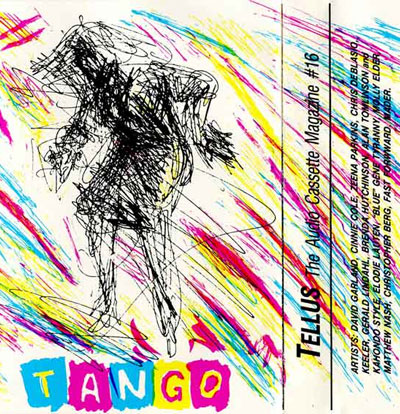

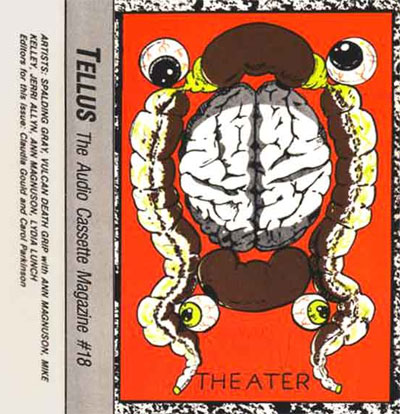

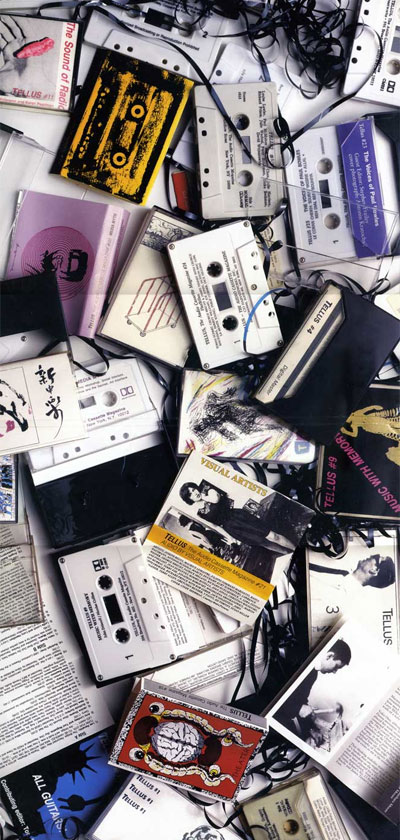

Launched in 1983 as a subscription only bimonthly publication, the Tellus cassette series took full advantage of the popular cassette medium to promote cutting edge music, documenting the New York scene and advanced US composers of the time - the first 2 issues being devoted to NY artists from the downtown scene. The series was financially supported along the years by funding from the New York State Council of the Arts and the National Endowment for the Arts.

Obviously, the Tellus publishers (visual artist and composer Joseph Nechvatal, curator Claudia Gould and composer Carol Parkinson, director of Harvestworks from 1987 on) never considered running an underground publication, rather envisaging the cassette medium as an art form in itself. A quite unique point of view at a time (the 1980s) when many self released cassettes blossomed through mail order or trade between artists, and when the cassette milieu was promoting DIY technique, even anti-art as a motto. The Audio Cassette Magazine never indulged into amateurism, their releases always focused, well researched and aptly curated. From the start, the founding members deliberately aimed at raising the profile of their cassette releases, sending issues to US public libraries and museums, for instance. The Tellus team launched the Harvestworks Artist-In- Residence Program along the cassette series, to promote independent artists' projects and provide them with a professional recording facility, named Studio PASS.

Tellus 'The Audio Cassette Magazine' was in activity for 10 years (1983-1993), witnessing the digital revolution taking place in the new media arts. Some points of comparison can be established with the Toronto based MusicWorks Journal and cassette, launched 1978, or with the ROIR cassette only releases of various musical styles, from Flipper to Lee Perry to Einsturzende Neubauten, launched 1981. Tellus published audio art, new music, poetry and drama, exploring musical spheres as diverse as avant-garde composition, post industrial music, NY no wave, Fluxus music, heirs of Harry Partch, avant rock, sound poetry, radio plays, tango, electroacoustic music, etc.

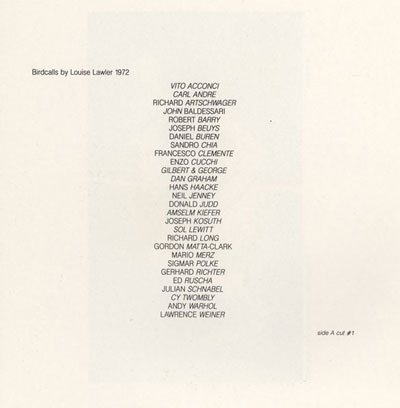

The series included some landmark sound works now regarded as historical: Louise Lawler's 'Birdcalls' (Tellus #5-6), Christian Marclay 1982's 'Groove' (Tellus#8), Lee Ranaldo 'The Bridge' (Tellus#10), Alison Knowles 'Nivea Cream Piece' (Tellus#24), etc. Tellus always championed women and gay composers, which was very needed in the macho experimental music sphere of the times. Curatorial policy has proved very efficient as well - asking specialists to compile a program in their own field insured state of the art results. Today, Tellus is mentioned as an inspiration to the opening of the Sound Art Museum in Rome in 2007. An exhibition was held at Printed Matter, NY, devoted to contemporary American cassette culture ('Leaderless: Underground Cassette Culture Now', May 12 to 26, 2007). It seems it's now time to reappraise Tellus' major contribution to the perception of independent music as an art form.

Birdcalls by Louise Lawler, 1972. Liner notes from Tellus #5-6

Explore the Tellus Cassettography at UbuWeb.

By Amanda MacBlane, from NewMusicBox, September 1, 2001

Christian Marclay cover art for TellusTools

TellusMedia, the Harvestworks Digital Media Arts Center record label, recently issued a 2-LP compilation of music previously released on the label. TellusTools comprises two 12" vinyl records of identical material, packaged in a gatefold cover designed by sound/conceptual artist Christian Marclay. Included in the liner notes are instructions on how to create personalized sonic experiences using two turntables and a mixer. Taketo Shimada, creator and editor of TellusTools, envisioned the project as a way to engage people in what he calls "active listening," where listeners are encouraged to create their own sound environments.

The basic premise is for people to create their own mixes using the albums as a point of departure, thus linking the experimental music of the 1980s to the present. Furthermore, these new compositions can be mailed to Harvestworks so the lifespan of the project can be extended into future endeavors.

Conceived as a much-needed alternative to radio, Tellus began as an audio cassette magazine, founded in 1983 by visual artist Joseph Nechvatal, curator Claudia Gould, and composer and now the executive director of Harvestworks, Carol Parkinson. For each issue, they collected and organized experimental sound art pieces around a specific theme, often inviting experts in a particular field to act as guest editor. In addition, emerging visual artists were asked to design the cover art for each issue. Shimada sums up the significance of Tellus during the 1980s: "Going through the history of Tellus is like going through the history of New York experimental themes in the eighties."

The idea for TellusTools was born when Shimada, a Harvestworks resident artist and DJ himself, was put on hold at Harvestworks. "I was working for Harvestworks on a different project and whenever I called Carol [Parkinson] she would put me on hold. When she put me on hold they played music in the background and from time to time, it was different music, and sometimes they would play music that interested me and I asked her where this music was coming from and she told me it was from Tellus back issues." When he approached Parkinson with his idea for a compilation, she was immediately interested in the project.

"In the beginning we just wanted to make a Tellus compilation that would present Tellus to a newer generation, because I myself wasn't around when the earlier Tellus was on the market," explains Shimada. Shimada and Parkinson decided immediately to ask artist Christian Marclay to come aboard to do the cover art and help conceptualize the project. Together, they decided that two LPs with identical material would be an ideal way to bring this music to a younger generation of sound artists and encourage active listening. "I like that you can actually touch the vinyl. It's more physical," Shimada said of the decision to use vinyl instead of issuing the compilation on CD. Parkinson adds, "It was always in our mind to do a 'Best of Tellus' and I think that the pieces just came together, with the interest in vinyl...with Taketo's interest in having new artists, a younger generation listen to the works...having Christian be this crossover artist who was a success, who successfully crossed over, and Harvestworks' need for a fundraising project which would get people interested in us as an arts organization."

At this point, the compilation had crossed over into a conceptual art piece that would reveal the compositional process by allowing listeners to actively participate in creating new sound experiences. Shimada embarked on the process of finding "songs that were not only playable in a club or in a bar but that also sort of crystallized...the early eighties to mid-eighties." When he was done, the set included works by a list of influential experimental sound artists including Nicolas Collins, Louise Lawler, Isaac Jackson, Kiki Smith, Alan Tomlinson, Joe Jones, Christian Marclay, Alison Knowles, Ken Montgomery, Catherine Jauniaux, and Ikue Mori.

In addition to introducing the music of Tellus to younger audiences, Parkinson explained that "taking this process of mixing sounds to create new ones that is so common to the DJ community makes it accessible to the sound art audience as well."

In the more distant future, Harvestworks may use the new pieces created through TellusTools in other endeavors. "The project just doesn't end with the LP." Parkinson points out. "We are recording the mixes in this series of special events that they are having and it [the instructions] does indicate that you can send your recording to Harvestworks and we'll collect them and then we'll see what we have. To extend the life of the project we can release a CD of the recordings that were made using the LPs as source material, but we'll have to see what it sounds like."

Visit the TellusTools website where you can hear and mix samples of all the tracks or purchase a copy of TellusTools from Harvestworks.

By Peter Graham (Jaroslav Šťastný)

Overtura by Alban Schelbert

The title refers to the well known story about Mozart who was criticized by emperor Joseph II for using "too many tones" in his music. The composer replied that the number of tones he used was "just right."

Many years ago a musicologist asked me to cooperate with him. He was planning to do some research on pitch-perception in which he would test people to see if they could tell if certain tone combinations were arranged randomly or rationally or by a musical idea. My task was to prepare the music samples. In this situation the question arose – how many tones do we need?

It is clearly impossible to distinguish whether it is by chance, a rational choice or a spontaneous musical idea if there is only one tone. But what about two or three, four or five? Although the project was never realized, it still makes me wonder.

Following the "official" line of modern music from Wagner through Schönberg, Stockhausen, Boulez and Ferneyhough, we can observe how musical material has been "enriched." While this may be admirable, I also find something greedy in this approach.

And when I think about the history of European music (i.e., music which is based on a hierarchical power structure), I sometimes wonder if the attraction isn´t the fascination with its form and its major works, but rather a fascination with the power it displays.

Fortunately, there is also another approach: the sophisticated simplicity of Erik Satie, which leads to the "empty-mindedness" of John Cage, the "open-cards play" of James Tenney, the humble music of Ernstalbrecht Stiebler, etc.

Returning to my first question "How many tones does a composer need?", I can only answer: "It depends who it is. And how many for him or her is just right."

In my last composition – the setting of a poem by Oldřich Mikulášek – I am not concerned with tones at all. Too much calculation and even professionalism could kill such subtle and intimate poetry.

For me, making music is similar to making love. And in love we are amateurs – if somebody is "professional," it is awful...

As in love, I prefer seeking my own path, without regard to the predecessors or followers, its public success or failure.

Here is my translation of the poem "Nýtování" (Riveting) by Oldřich Mikulášek:

The Moon

in the Sky

Wants nothing

Just to be

Like a rivet

And to tighten

The Heaven.

It is the time

Of your dark eyes

Behind the eyelids

Sealed in themselves.

By Kyle Clyde

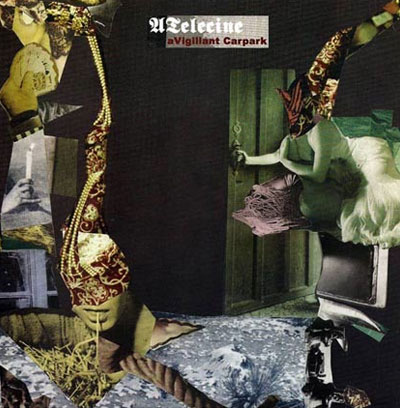

Todd Brooks's cover art for Atelecine's aVigillant Carpark

Sasha Grey might not be the first lady noise artist to play dom for bread or spread eagle for Richard Kern, but this brown-eyed vixen's day job has already garnered more mainstream media attention than perhaps the entire noise scene itself. She could have gone DIY with her first two albums and self-released. With the income she's generated from porn, acting, and modeling, she might have purchased about a dozen vinyl lathes and still had the capital left over to place a down payment on a small stadium in Detroit. She could have also begged gal pal Billy Corgan to hook her up with the cell of a mid-sized indie label exec. Instead, she chose to release both of her recent albums on Pendu Sound Recordings, a Brooklyn-based experimental label specializing in editions of 100 pressings or less.

The band Atelecine is a collaboration between Grey and the marginal Pablo St. Francis. (We find him buried deep within the liner notes.) While Grey's image is featured prominently in band MySpace photos and albums, St. Francis's visage is all a blur. Pendu's promotion of the band as “Atelecine (feat. Sasha Grey)” leaves potential buyers wondering whether his role in the band is even worth noting at all. Though both members are said to be responsible for vocals, effects, and strings, the extent of each members' involvement is left to the listener's imagination.

Their first release was an EP seven inch titled "AVigillant Carpark." In this one, Sasha Grey leads us down a path of minor-key scuzz drone, followed by more melodic, arranged landscapes. Yes Atelecine is experimental, but these tracks are not a collection of improvisations. Yes it is dark, but we do not get the sense that these songs are ripped from the subconscious of someone who has met Death at its crossroads. These are composed pieces meant to induce a certain train of thought in the listener—it is the soundtrack to a life. In this narrative almost-legal young adults kill time until maturity. The scent of mail order salvia thickens with cloves as an analog signal of Molder and Scully illuminates the apartment's carpeted floor. These Lolitas, cat ears sewn to their Type O Negative hoodies, are the new girls next door. She's your weird best friend who says she's bisexual; your older sister who dyes her hair with India Ink; your first time doing that in the back of a hand-me-down Oldsmobile. Atelecine is teenaged angst suspended in time. It is Sasha Grey, the seasoned 21-year-old porn star, finally acting her age.

It is not unheard of for a noise band to release an album without ever having set foot onstage. The history of underground music is filled with tall tales of painfully introverted geniuses laying down wicked mono tracks in mom's basement. However, Sasha Grey may be the first recognizable public figure to have released an album on a noise label without ever having toured or played a show. Therefore, it's hard to know what the future holds for Atelecine—are they exploring new territory or still trying to find their sound? Will Atelecine cross the river Styx or will it continue to watch from the shore? Only Sasha Grey knows for sure.

Atelecine's new album "A Cassette Tape Culture LP" will be released in Jan. 2010 on Pendu Sound Recordings. It will be released as an LP alongside twenty-three limited edition cassette tapes.

By Derek Miller, from Stylus Magazine, October 2007

For those of you who've been following Stylus' year-end thoughts over the past few years, you're probably going to be familiar with the backstory for mine. It's a running thread. As one of our most frequent commenters slurred in 2005, "when Stylus goes MySpace." That was probably Dom actually, using a pseudonym. In any case, another year has passed almost—my, gasp, thirtieth—and we here at Stylus are in closing-time mode, not only for a year quickly giving out to winter but for this little site we've run.

At the year's start, I severed what I thought was the final thread of my life with my ex-wife. As the Minneapolis condo market began to sour, I was lucky enough to get out at the last moment. In the coldest weekend of January, I moved into an apartment a few blocks away, in the city's Loring Park area. My heat, unfortunately, didn't come on ‘til the next week so I spent a long weekend in sweaters and a Herringbone jacket, never more than two feet away from my space heater. The move was an important one to me though, as I was finally out of the home I'd shared with my ex. I was disconnected from the final part of my life, or so I thought.

Of course, as I found out in the coming weeks, I'd also see my ex more than I'd seen her in the past couple of years, but for courtrooms and chats over Bloody Marys or coffee about selling the condo. I'd go out to the corner store and see her in summer dress and sunglasses, long-legged and season healthy. Beautiful. I'd leave for work in the morning and bump into her finishing up her morning jog, recognizing her jagged, uneven gait from across the park. I'd park my car and see her own six cars down—her collegiate bumper sticker pasted in its back window. I began to think I'd made a mistake in staying in the neighborhood, as though cutting that final thread had only been a way of tying another, much closer bond. I was over her, right?

But then I'd see her. Maybe that's inevitable. You overlook the nastiest of end-points; the things said in leaving and divorce; the way she wouldn't speak to you for three weeks after walking out, you in that place and all its new quiet. You think of the other things, open-ended times, like when you were driving her home from D.C. after she graduated from college, and she spilled iced coffee all over herself. You had all day to drive, and she was soaked in milky drink. She should have been upset, quick to clean it all off. But she opened up in a great gasp of laughter that shook you both. Regardless, I felt guilty for still missing her, as though any rational human being should have gotten beyond that initial grip of absence. And yet all it took was a glimpse, the two of us alone in this summer morning park, to make it clear I couldn't rationalize the way I still felt.

Summer wound past. I watched from my apartment on the park as the trees finally came to color, and as the grass then lost its own. This summer was one of Minneapolis' hottest. A drought ran down its belly. The park was corn-stalk yellow by mid-July, only to be relieved by an October of dense curtains of rain. On a day in early August, I spoke to Stylus Editor-In-Chief Todd Burns, and immediately realized that the one most important link back to those years, the only one I'd perhaps taken for granted, was about to be cut. Burns was closing down Stylus. I was stunned, though of course I shouldn't have been. But, in that odd second, I understood that the sale of my home was merely a marker, a symbolic shutting. The end of Stylus, a place I'd put so much into over the last few years, especially in that time post-crash, was a far more significant close.

My ex had actually helped me write my ‘application'; we'd sprawled across our rug, heads together and crossed back in the air, and sketched out what I realized at the time was a self-consciously arrogant missive. Take me or fuck off, but I think you'll take me. I had never written about music though. I had never written about much of anything. I had read writing about music though. I thought it was a way to put my creativity into something almost patently a-creative, all that "dancing about architecture" horseshit come to mess. Really though, Stylus became a job I placed above ‘career.' The reasons for Stylus closing were obvious, and I won't get into them here. They were concerns I'd had myself. But when Todd told me it was over, I didn't bother to argue or try to force a reprieve as he thought I would, clearer-heads-shall-prevail style. I knew he meant it, and I knew he was probably right.

Stylus, like most such ‘zines, has a message board. When the announcement came out to the staffers, shit went Black Friday. Staffers turned to getting something running that could be Stylus Version 2.0. Calls went out. Talks were had. But as the weeks went by, the focus changed to one of memory, nostalgia. I think most of us soon realized what I'd known all along: that Todd Burns was the only person who could actually have made Stylus so dependable, so Monday-through-Friday. Honestly, then, much of this essay should be a testament to him. He listened to far too many bad pitches of my own, too many ideas for too many columns that couldn't possibly get past week-five. And then he told me why they couldn't work (though the fucker also turned down some great ones). But more importantly, he gave all of his writers creative range and freedom, something not too many people in his position are willing to cede so absolutely.

Like any writer, I look back at some of the things I've written here with embarrassment, but the very fact that I could do so—that little of my own ‘prints and long-windedness was cut, that I was left to fend with my own mistakes—is a testament to Burns as a creative director more than as a typical EIC. For many that might sound like a critique. For me, a ‘writer' who happens to find music writing fits his need for outlet more than, say, short stories, he was editor who understood and empathized with his writers more than he emphasized his own needs for "Stylus, my baby." I'm not sure many others would have given the go-ahead to a piece like A Kiss After Supper—such a difficult, winding message-of-love but one of my most adored columns from the site's history—and I'm damn sure nobody else would have published something like Stew and my piece on Kristofferson, something intended far more for the two of us and our untended, rabid tongues.

Before Stylus, I'd never have believed you could become so close to people you'd never met. In space that lacks physique, you kind of meet as avatars. The board was a way for so many of us to piss away empty time at work or late at night, to gossip and needle and call-foul at music, sports, our jobs, drinks of choice. I think we all came to a persona of our own more than perhaps we were ourselves. A dress-up, extroverted place for what I expect are really a room-full of introverts (spoken like one. . .) It was dreamspace, the most virtual of realities, but it was also a place where those of us who'd been around for a while began to feel we could come, first-coffee in the morning, to put some kind of steady perspective back in place. But it only worked because we came to know at least a bit of something about each other by what we'd read and written. There was a frankness gained by putting so much of ourselves in pieces about music—or pieces about music which often had nothing to do with music. We pressed and confined each other, in turns, with a challenge of putting something in writing, formally or informally. Often, we'd shape our pieces by thoughts we'd come to in discussion with each other—or by things we'd read on Stylus that day.

So secrets, let's see. I don't mind telling you that Todd Hutlock is the most obsessive record-collector I've ever known. I asked him last week just why the fuck he was bothering with A Bigger Bang. "It's the only Stones studio album I haven't heard," he said. Now, that's patently absurd, right? I gave up on that band in '81. Didn't you? But there's something sort of charming in somebody so willing to stick it out, to lend an ear against his better instincts ‘cause the band once gave him everyday-spoil—though, of course, we (I) at Stylus had to let him hear about it.

Or that Josh Love, Ian Cohen, and Drew Gaerig might just have the best sports blog in them that you'll never read. Or that Andrew Unterberger has the mind for pop-spoil and music minutiae, as we now know from his win at this year's World Series of Pop Culture on VH1, that Hutlock has for records. Or that Nick Southall uses his digital camera to document his waking hours in a second-to-second manner. Like, erm, every fucking second. Or that Alfred Soto, behind that witty Miami academic, is one of the warmest, most-constructive readers of the site, from without or within. He was a child once (though he doesn't want to talk about it). Or that Mike Powell really enjoys Trader Joe's Greek yogurt for breakfast. With cereal. Or that Justin Cober-Lake has two of the most adorable children drawing breath—yes, fatherhood at Stylus.

Stylus is gone as of this Wednesday. Halloween. Nice one with that, TB, but smiles to you anyway, sir. For me, the place that had seen me through my late-twenties and so much sticky turmoil is disappearing. All of these people I've come to read, and then to mock and rib and laugh against in kind ‘cause they really do listen to say some awful shit sometimes (don't we all), will scatter. And honestly, though in the past I've put perhaps too much of my own life in these pages—been perhaps too open and unreadably close—this piece is really written for my colleagues here at Stylus. I'm not ending this year in new love like the last. I'm speaking of an old one that's about to run dry.

It's closing time and I'm feeling, like the rest of us, pretty nostalgic. For the new ones—even though Dan Weiss loves FUCKING everything he hears and Patrick McKay keeps trying to convince me The Darjeeling Limited is anything but garbage—and those who have been so important as guides for Stylus—TB, Nick, Mathers, Love, Hutlock, Alfred, Mike, and the rest. Stylus will be for me a final removal from something I thought I'd ended earlier this year with a move to a new apartment in February cold. I think you're still going to see a lot of us around, in various papers and non-paper places, but Stylus was the place we came for both twenty-page Radiohead threads and fake-industry-email stunt reviews. As it's a bit too early still to wish you all a Happy New Year, I guess it's got to be Happy Halloween. Or maybe just goodbye and goodwill.

The Bluffer's Guide to Stylus by Todd Burns

From Deutsche Welle, Nov 15, 2005

The remains of the Domino Day 2005 sparrow, being held by Kees Moeliker of the Natuurhistorisch Museum, Rotterdam.

For a precious few seconds, the hard work a team of domino fanatics had put into painstakingly setting up more than 4.1 million dominos looked in danger of collapsing before their eyes.

A sparrow had somehow snuck into the hall where the Domino team would look to break the domino world record during a show broadcast live on private German TV channel RTL this Friday. The bird knocked down 23,000 tiles and there was nothing anyone could do.

After calling in an animal expert who tried unsuccessfully to catch the bird, the angry domino fans opted for heavy artillery. A hunter took aim and shot the sparrow, ending the threat to the World Record attempt.

"Regrettably it was the only option," said one of the team members.

But the measure has enraged animal protectionists. Germany's Animal Protection Association cited animal protection laws which allow killing only on "reasonable grounds." A sparrow threatening a hall full of dominos apparently isn't one of them.

RTL said the team did all it could before ending the bird's life. The world record attempt -- during which the domino team will try knock down 3,992,398 of the 4,321,000 tiles set up for the event -- doesn't appear to be in danger.

"We can rebuild everything with a few overtime hours," they said.

From Expatica News, Nov 15, 2005

At least seven organisations have become involved in the saga surrounding the sparrow shot dead on Monday.

The little bird's crime was to knock over 23,000 of the 4.3 million dominoes laid out for an attempt to break the domino toppling record in the Dutch province of Friesland on Friday. The decision was taken to shoot the bird after attempts to capture it alive were unsuccessful.

Animal rights group Dierenbescherming and the provincial authority have both appointed officials to investigate the shooting dead of the bird with an air gun. Dierenbescherming said sparrows are a protected species and a licence is required before killing one.

Meanwhile, the man who fired the fatal shot has been threatened with death.

Animal management company Duke Fauna Beheer which employs the man has gone to the police. "We have not made an official complaint as that would be no use. But if an idiot comes around here, we want a direct line to the police so they can come quickly to help us," the company said.

The bird flew into the FEC exhibition centre in Leeuwarden in the north of the Netherlands on Monday where 4,321,000 domino bricks have been arranged for Domino Day.

Singer Anastacia is to knock over the first brick of the bid on the world record on Sunday in a show televised live on Dutch television channel SBS 6. The bird couldn't wait.

"The sparrow knocked over 23,000 bricks. Luckily, we have 750 safeguards built in. Otherwise we could forget about the world record," said Robin Paul Weijers, the organisers of Domino Day 2005.

The investigators appointed by the animal rights group and the provincial government have the power to issue a warning, or lodge a complaint with the public prosecutor's office.

The German animal protection group has also complained to broadcaster RTL about the killing of the sparrow. RTL will broadcast the Domino Day event in Germany.

Endemol, the broadcasting company producing Domino Day for Dutch channel SBS 6, has hired extra security for the FEC centre. It did this partly because Dutch Radio DJ Ruud de Wild has offered a reward of EUR 3,000 to anyone who topples the dominoes prior to the start of the event.

By Ben Rand, from Being There, 1979

I have no use for those on welfare, no patience whatsoever, but if I am to be honest with myself, I must admit that they have no use for me either.

I do not regret having political differences with men that I respect. I do regret however, that our philosophies kept us apart.

I could never conceive why I could never convince my kitchen staff that I looked forward to a good bowl of chili every now and then.

I have heard the word "sir" more often than I have heard the word "friend," but I suppose there are other rewards for wealth.

I have met with kings; during these conferences I have suppressed bizarre thoughts. Could I beat him in a foot race? Could I throw a ball farther than he?

No matter what our facades, we are all children.

To raise your rifle is to lower your sights.

No matter what you are told, there is no such thing as an even trade.

I was born into a position of extreme wealth, but I have spent many sleepless nights thinking about extreme poverty.

I have lived a lot, trembled a lot, was surrounded by little men who forgot that we entered naked and exit naked, and that no accountant can audit life in our favor.

When I was a boy, I was told that the Lord fashioned us from His own image; that's when I decided to manufacture mirrors.

Security. Tranquility. A Well Deserved Rest. All the aims I have pursued will soon be realized.

Life is a state of mind.

By Leo Marks, 1943

The life that I have

Is all that I have

And the life that I have

Is yours

The love that I have

Of the life that I have

Is yours and yours and yours

A sleep I shall have

A rest I shall have

Yet death will be but a pause

For the peace of my years

In the long green grass

Will be yours and yours

And yours

Catepiller by Amelia